We met at 7 am to answer a question. For the previous couple of months, I’d been wandering Lake Jackson’s exposed bed, and observing the area around Porter Sink. The lake had been down since November, and on and off since June of 2021. With all the rising and falling of water, I began to wonder how plants and animals reacted to this ever changing habitat. At the same time, Cait Snyder wondered more specifically about birds.

Cait is Resource Manager for the Lake Jackson Aquatic Preserve. In her own wanderings around the lake, she’d gotten to know a group of birders who had been especially active since the June 2021 dry down. Cait could see a lot birds in the lake when it was down. But it’s one thing to see. She wanted to know, numerically- do more birds, and bird species, visit when the lake is down?

One path to an answer could lie within our phones. eBird is a citizen science app developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Users make lists of the birds they see at a location, at locations all over the world. Cornell then harnesses the data collected to use in their research. But they also make it available to the public. One way is by letting us sort data at “hot spots.”

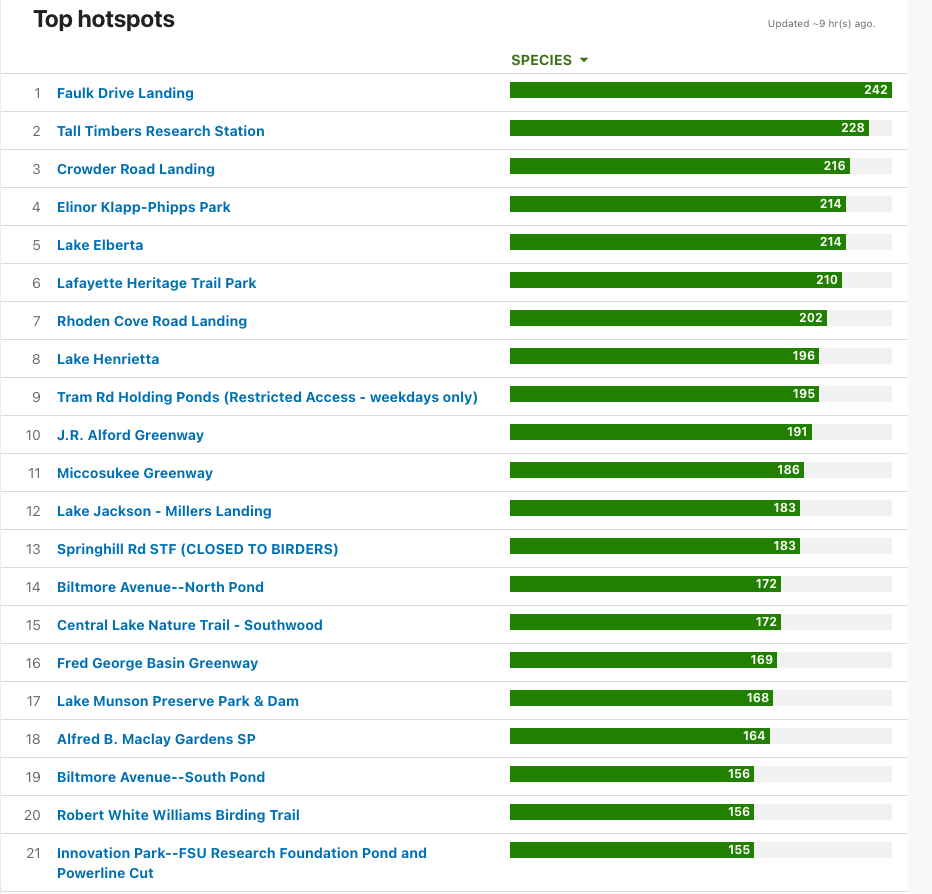

Hot spots are places with a lot of bird observations. Lake Jackson has several, including four of the top ten in Leon County. We could look at the data from over the years, and see when birds were more numerous. To help us accomplish this, Cait rounded up the top three eBird observers for Lake Jackson. And for good measure, we enlisted the help of Apalachee Audubon’s (and Tall Timbers’) Peter Kleinhenz.

We set a date to meet, and then-

Rain filled the Porter Sink basin

The idea was to take some photos of birds in and around the dried down lake. And then, a week before we were to meet, Tallahassee received a good rain.

The area around Porter Sink was full again, at least for the time being.

To recap- Lake Jackson, like our area’s other sinkhole lakes, periodically dries down. During long periods of low rain, the lake level dips, as does the aquifer directly beneath the lake. Every few years, both are low enough that, over the course of a few days, the sinkhole basin goes completely dry. Little streams trickle from fuller sections of the lake, turning into waterfalls at the edge of the sink basin. A good bit of the lake still holds water, and so the little streams constantly feed the sink.

Since 2021, the shallower sections of Lake Jackson haven’t held water for more than a month or two at a time. Would this last rain be enough to keep it wet for longer than that? It’s hard to tell. Because it was winter, though, Cait said that the lake would stay full for a little while.

“In the wintertime, there’s less emergent aquatic vegetation,” Cait said, “so less evapotranspiration.” It’s a shallow lake full of grasses, water lilies, pickerelweed, and so on, and all of those drink the lake water and evaporate it into the atmosphere. A lot of that dies back in the winter, and so more water stays in the lake basin. As I write this, though, spring is upon us, and the landscape is greening.

The day after it rained…

The rain changed the nature of our outing, but not necessarily the focus of our video. We were a week away from our shoot date, and I wanted to see the lake right after the basin filled. I drove down to Faulk Drive Landing, which is a short walk from Porter Sink.

The lake was fuller, but there were mud flats and shallow areas throughout. Every one of those was covered with birds. Near the landing, ibis and greater yellow legs were pecking their large beaks into met mud. I could see one yellow legs in particular take worm after worm out of the soft earth.

A large flock of white pelicans rested not too far off. On one bar, I watched as a juvenile bald eagle was joined by another, and then an adult. Soon, there were six eagles (two adults and four juvenile) frolicking on the bar as killdeer gave them space.

Wading birds, swallows, grackles, coots- birds were moving all around the lake. I wondered about our question. I remember seeing a lot of birds when the lake first dried down in June of 2021, and again in November 2022. And here are a lot of birds a day after it filled back up. When water moves, birds become active.

Just a week later, during our shoot, there were not quite so many birds on the water. And they weren’t moving like they were right after it filled. But there’s more for birds here than the lake itself.

Birding habitats around Lake Jackson

Back to 7 am on a warm February morning.

One of our eBirders, Juli deGrummond, didn’t wait until seven. As we convened, she let on that she’d already started her eBird list, and that the list contained a barn owl that they’d all been observing here of late.

The owl wasn’t making use of the lake habitat, but instead was found perched in a tree by a grassy area next to the lake. “Faulk Landing is absolutely my favorite birding spot,” Juli said. “It brings together a variety of habitats. You’ve got the brushy area as you’re walking up and you’ve got grassy trails that are great for sparrows.”

The Brushy Area- Walking up to Faulk Drive Landing

Since June of 2021, Faulk Drive Landing has been closed as a boat ramp. Car access is blocked from the parking area, and you walk through a tangled canopy to get to the ramp. The trees are thick here, and overgrown with vines through which you can see the grassy fields on either side.

For months, I’ve taken my time walking to the ramp with my camera. Birds are in all the trees, and especially in the ditch that runs behind them to the left. In the winter months, we see the common migrants- robins, yellow-rumped warblers, eastern phoebes, and chipping sparrows. We saw a brown thrasher in a nest, and an eastern towhee kicking up dirt. A downy woodpecker worked its way up a branch, and the air was dense with the sounds of grackles and red-winged blackbirds.

Faulk Drive Landing is Leon County’s top eBird hotspot. The rising and falling of water around Porter Sink is a likely factor. But, compared to the other boat landings around the lake, there is quite a lot of room to roam the habitat to either side of the ramp. This is where birders spend a lot of time looking for the less common birds.

Grassy Trails- walking old boat lanes

After you emerge from the canopy, There’s an opening surrounded by grassy fields. Depending on the lake’s level at the time, this was the ramp, or the shallow area just beyond it. Trails lead off in either direction, parallel to the shore.

Cait said some of these edges were cut by boats when the water was higher. Just after the rain, there were large mucky puddles, but there was still a bit of dog fennel between us and the lake’s current edge.

We first walked north along the trail, and Cait pointed out a dock to our left. Keep in mind that property lines extend to the ordinary high water zone of the lake (loosely speaking). While wandering around at any of the boat landings, be mindful to stay off private property.

While the lake birds are often large and out in the open, here the tall grasses hide smaller, and often less common, birds. Eliza Hawkins started talking about sparrows, which can all look dull and brown at a distance. Through a scope or the long lens of a camera, though, they can be surprisingly colorful and distinct.

“When you get into the differences of these sparrows, they’re beautiful.” Eliza said. “There are dozens of sparrows [here] and some very rare ones… white crowned, clay colored, white throated, LeConte’s, Henslow’s, grasshopper, Vesper.”

The trails here reward patient bird watchers. The larger, easier to see birds are in and by the water. If you like birds but aren’t a hard core birder (yet), this is where you might want to head first. And if you want to see a lot of birds, head there right after it draws down- or after it fills back up.

Dry down on Lake Jackson- what do we see?

I went a couple of days after Lake Jackson dried down in June of 2021. I saw those large wading birds that are so conspicuous, in large numbers where the water retreated. These are fish and amphibian eating birds, and the lake’s fish had all of a sudden become concentrated in these smaller pools of water.

“The birds will use the moving edge of the water as a place to target and take the opportunity to forage,” Cait said. “There’s a big wader bird diversity here. Egrets and herons, wood storks are all here and they all work the edges.”

Another place where water pools up is the sinkhole itself.

“Right after the drawdown, it’s just a massive influx and can be quite interesting.” Eliza said. “It’s the best osprey photography, you know, and [in] the little sinkhole, there’ll be hundreds of big fish. So I just have this great series of ospreys with huge fish.”

But also, the mud flats

When the lake is down, many of us come here just to look at the sinkhole basin. In flat Florida, this is visible and impressive geology. Once here, the large wading birds along the edge of the remaining pools of water draw the eye, and the small streams crossing the landscape. It may not occur to us to check out the large, brown fields of muck surrounding these features.

But these mud flats are a major part of the bird habitat here.

“When the lake drains, you’ve got all this mudflat,” Juli said. “And the mudflat is for me the part that I really love.”

“I think just a function of having more exposed mud brings in a lot of shorebirds,” said Peter Kleinhenz. “[And it] brings in a lot of things feeding on emergent insects that are coming up.”

When the bottom is covered, invertebrates in the muck are inaccessible to small shorebirds. All of a sudden, a new food source becomes available to them.

Think of shorebirds on the coast as the tide goes out. The sand is wet, and a lot of small crustaceans are left behind in it, easy pickings for short legged and short billed birds. Shorebirds with longer beaks pierce through wet sand more easily than dry, and find worms and other critters beneath the surface.

A dry down is like the tide going out, but on a larger scale and for an extended amount of time. Every time the lake fills somewhat and drops again, the muck is moistened once more.

But are there more birds in Lake Jackson when it dries down?

Lake Jackson is not surveyed in the same way as the St. Marks Refuge or Wakulla Springs. At both of those locations, volunteers systematically count birds at regular intervals. The eBird users we interviewed come as often as they can, based on work schedules and other obligations. And if there’s an interesting observation, they let each other know to come on down. They see a lot, but it’s not systematic.

So we may never know absolutely if there are more birds in the lake at one time or another.

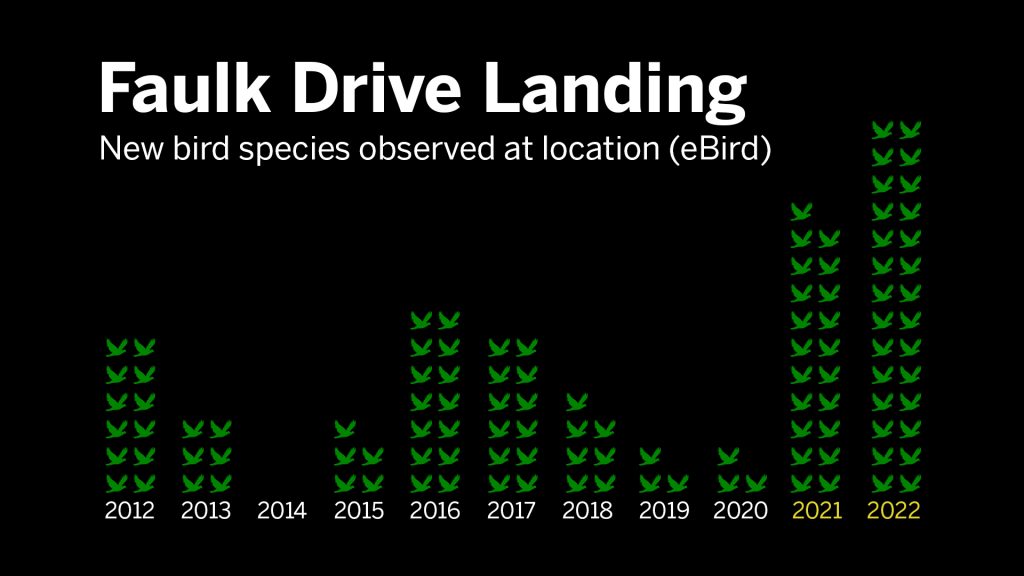

We can, however, look at the diversity of species. To do just this, Juli came up with a novel approach.

“So on eBird,” Juli said, “there’s a a function where you can go to a hotspot, which Faulk Landing is, and you can put the setting on ‘first seen,’ and see when a species was first seen in this location.”

eBird launched in 2002, still several years before smartphones became ubiquitous and making lists became much more convenient. It’s reasonable to assume that all of the common species- ibis, mockingbirds, great blue herons, cardinals, etc.- had their first IDs here early on.

For the less common birds, perhaps, the species marked as first seen may be new visitors to the lake, at least within recent memory. Juli made a list of such species, and found the numbers to be much higher in 2021 and 2022.

So, were more birds observed because of the dry down?

It’s too big a jump to discount it. The dry down almost certainly led to there being more observations. But not necessarily in the way you might think.

“Like Juli was talking about earlier,” Peter said, “the last couple of years, the number of species seen here has just exploded. And part of that is certainly the birds coming here. Part of that is a lot more people visited during the dry down.”

More observers, more potential observations. Because lists are public, if one user spots a species of interest, others will take note. The more serious birders visit a spot, the more likely they are to find species that a casual observer would miss.

That’s the double edged sword of citizen science. While it increases the raw amount of data available to researchers, free of cost, it depends on participation. If the diehard eBird users who visit Faulk Drive Landing find another spot they love, they may visit less, and observations would go down- regardless of the number of birds there.

More birds to observe vs. more observers

Likely, the jump in new species spotted is a combination of birds coming in to take advantage of the change in habitat, and that more birders came out to see them. After all, serious birders only come here because they expect to be rewarded for their time. Something has to keep them coming back.

And the more data they collect, the more us casual bird watchers and other nature enthusiasts can learn about this place. I’ve only ever completed one eBird list, but I like checking hotspot info for places I visit. A large diversity of birds is an indicator of a healthy ecosystem, which you might enjoy even if you’re not big into birds.

“If you see if you see that a lot of birds have been seen someplace, you automatically know it’s got a diversity of habitats,” Peter said. “It’s probably got good access… Some of the coolest places I’ve been to in recent years while traveling in other states, and in Florida, have been because I found them via eBird.”

And for the group we gathered today, it can be a way to find friends who share a common interest. It’s how they met and started birding together here. Mike Dayton has only been birding since 2020, and without eBird and this community of friends, he may never have become serious enough birder.

“Merlin and eBird helped tremendously,” Mike said. “Really, these guys have helped me learn a lot too. Especially in the early days when, you know, I’m looking at a more common bird and I’m like, What’s that?”

Further reading/ watching

Speaking of “what’s that?” – Mike Dayton mentioned Merlin helped him learn birds; it’s another free app from Cornell. It has a visual ID component, like iNaturalist, but what I’ve enjoyed this year is using the sound ID function. When you start a recording, it listens to the bird calls around you and makes a list.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into eBird, Apalachee Audubon put together a tutorial on their YouTube channel. It’s hosted by Peter Kleinhenz and Tall Timbers ornithologist Heather Levy, who we’ll get to know in an upcoming segment.

Lastly, if you’re interested in learning more about Lake Jackson, I have a couple of WFSU Ecology Blog posts for you. If you want to learn more about dry downs and how it affects the ecology of the lake, read this post from 2021. A year later, a FAMU researcher discovered a new species of crustacean that, so far, has been found nowhere but Lake Jackson. There are millions of amphipods and isopods in Lake Jackson that you’ll likely never see; without them, though, there would not likely be so many birds.

What did we see?

The next two sections are about what birds we saw in the video, and some non-bird related things that didn’t make it in. We’ll start with the latter. An eBird hotspot list won’t tell you about all the other cool nature in a spot, but any hotspot is likely to have much more than birds.

Other finds in the Lake Jackson Habitat

Earlier we saw a photo of an osprey with a bluegill. These fish make small depressions in the lake bottom in which they nest. When Lake Jackson dries down, you can see these little fields of craters. They’re most intact right after a dry down. I took the photo above two months after the November dry down, and the craters had started to smooth out and become less defined. I can see it in my photos from throughout November and December. But then it rained in early January, making little puddles in the nests which left these rings around them. A little Tallahassee moonscape.

I love birds, but I truly geek out on insects and other invertebrates. While I was interviewing Peter, I noticed a white blob in a bare shrub. I figured it was an insect pupa and made a note to check it out when I was done. I’ve never seen a spider look so cute. Cait checked with an entomologist, and this could be the case of a bagworm caterpillar.

We paid a short visit to Crowder landing, which is where I interviewed Eliza and Juli. As they scanned the tree line with their scopes, they found an odd shape up high. Anyone who’s followed the blog for a while knows my affinity for bees, and while I prefer our Florida native bees, it was cool to see a wild honeybee hive.

We don’t see scenes like this in Florida. This reminds me of rivers I’ve seen out west, trickling through barren, wide open landscapes.

Canyons and waterfalls aren’t typical of Florida, either. It’s this kind of scene that brought people out here a couple years ago.

Birds in the video

January 25, 2023 (except where noted)

00:00 A flock of white pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) right after the lake filled.

00:03 White ibis (Eudocimus albus) feed at the edge of a mud flat.

00:07 A single adult bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) on a flat.

00:10 Porter Sink on January 4, 2023.

00:13 The Porter Sink Basin from Faulk Drive Landing, a day after it filled.

00:15 Ibis and greater yellow legs (Tringa melanoleuca) feed at the water’s edge. Greater yellowlegs are a winter visitor to our area.

00:17 Great and snowy egrets gather in a shallow, lily pad covered part of the lake following the June 2021 dry down.

00:21 Greater yellow legs picks worms out of the mud.

00:34 Great blue heron (Ardea herodias) with fish in a pool of water in a dried down Lake Jackson, November 15 2022.

February 1 and 2 (except where noted)

01:28 A chipping sparrow (Spizella passerina) in the ditch along the path to Faulk Drive Landing. Another winter visitor.

01:33 Yellow-rumped warbler (Setophaga coronata)on a dead dog fennel branch. Also a winter visitor.

01:35 Downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) picks at woody, leafless vines.

01:38 Eastern towhee in the ditch.

01:45 Savannah sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis) in a path through grassy fields. Also a winter visitor.

01:53 A far off American kestrel (Falco sparverius) in a tree.

02:21 White pelicans again. These are migratory birds, but over the last year, they’ve been present in the summer and winter.

02:31 Ibis on the mud flat again, January 25, 2023.

02:37 American coots (Fulica americana) swim along the shore.

June 7, 2021, after dry down.

02:53 Great egrets, snowy egrets, little blue herons, and ibis in lily pads.

03:00 Left to right after wood stork lands- Adult ibis, juvenile ibis, little blue heron (Egretta caerulea), wood stork (Mycteria americana), standing on mud flat. I often see wood storks in mud flats rather than wading in water.

January 25, 2023 (except where noted)

03:26 Sparrows pick at mud flat. They were kind of far off.

03:27 Grackles feed from shallow water.

03:32 Two adult bald eagles land next to three juveniles on a mud flat. The juveniles aren’t fully brown, and are starting to molt into white feathers.

03:58 A series of photos of osprey with fish, taken by Eliza Hawkins, taken after the June 2021 dry down.

04:14 Wood stork on mud flat, also after June 2021 dry down.

04:20 Dozens of American coots off Crowder Landing, February 1, 2023.

04:52 White pelicans in a lily pad covered area shortly after dry down, July 11, 2022.

06:01 American cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) in brushy area, February 14 2023.

06:12 Snowy egret (Egretta thula) in shallow water.

February 2, 2023 (Unless otherwise noted)

06:14 Eastern Phoebe (Sayornis phoebe). A winter visitor which often wags its tail.

06:18 Red winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) calls.

06:22 Miller Landing, across the lake from Faulk Drive Landing, March 8, 2023.

06:28 Far off egrets and ibis in lily pad covered portion of lake, July 11, 2022 after dry down.

06:36 White pelicans swim through grasses. You can kind of make out a cormorant through the grass as well.