The Bradwell Bay Wilderness is dark and mysterious- and full of life. In part 2 of our salamander adventure, Bruce Means searches the swamp for the southern dusky, a critter that has disappeared from almost everywhere else.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

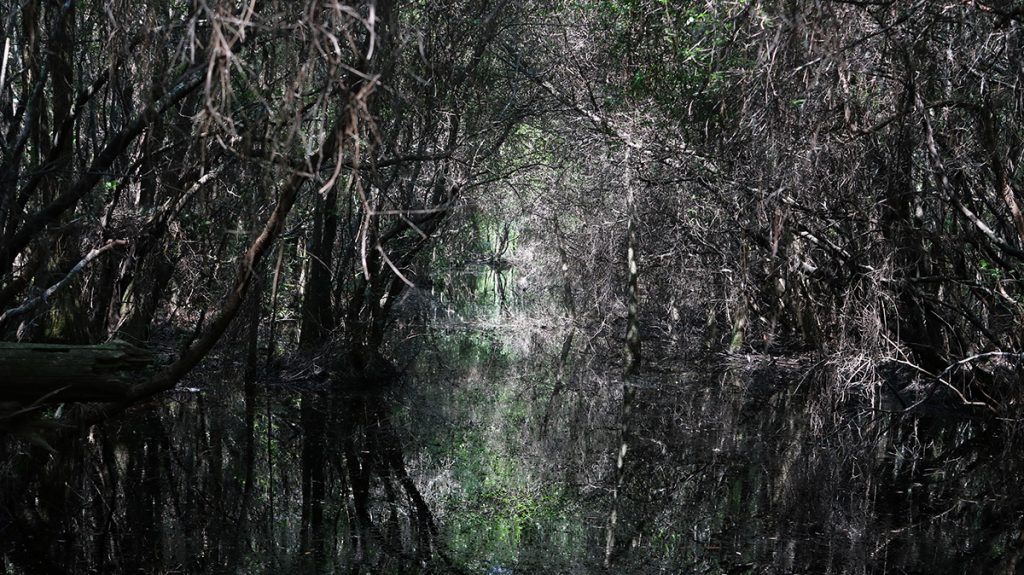

Is there something you love doing enough to do it for over fifty years? Some do, and that’s why I’m here today. I’m following Bruce Means into a titi swamp in the Bradwell Bay Wilderness. He’d scour this place as a Florida State University graduate student in the 1960s, and today we’re on the same mission.

We’re on the hunt for southern dusky salamanders.

It’s the middle of the summer, and it’s been a rainy one. There’s water on the ground, unlike when we hiked out here last December with Dr. Means’s son, Ryan, and his family. It’s a little higher than Dr. Means likes for salamander searching. He works the edge of the water with a dip net, raising a scoop of leaves to his face and picking through it. No luck so far.

The yellow flies are biting, but it’s not as bad as in other years, Dr. Means says. We haven’t followed the Florida National Scenic Trail into the heart of the swamp, where the old, big trees are. We followed it to where the pine flatwoods transition to wetland, splashing under a canopy of black and red titi. Then Dr. Means took us off trail, which, when flooded, looks the same as the trail. I can see why there are so many stories of people getting lost here.

It’s not an ideal work space for everyone.

Somewhere in his time at FSU, Bruce Means figured out the benefits of studying something that didn’t interest other researchers. In his graduate work on southern duskies, he put in a lot of dirty work in swamps, ravines, and other generally wet and mucky places. And when he’d finished his graduate work, he had discovered a new species.

Bruce Means after a couple of hours searching for southern dusky salamanders in the Bradwell Bay Wilderness.

A New Species of Salamander (1972)

Bruce Means did his masters and Ph.D. work on the southern dusky salamander. Over the course of sampling over one hundred wetlands, he noticed differences between some of his southern dusky specimens. Does this sound similar to last week’s story on his discovery of the Hillis’s dwarf salamander?

Salamanders are small and secretive, and many of them live in difficult places. Many species look a like. And there aren’t a lot of people studying them. It makes sense that if a scientist takes the time to visit a lot of these difficult places, and repeatedly look for these little guys, they’d find something new. Over fifty years, they’d find a few new things.

So when he brought his dusky specimens back to FSU and cleaned them up, Bruce Means could see that he was looking at two sets of salamanders with distinct characteristics. And in 1972 he named a new species of salamander- the Apalachicola dusky.

The Apalachicola and Southern Dusky Salamanders- Telling them Apart

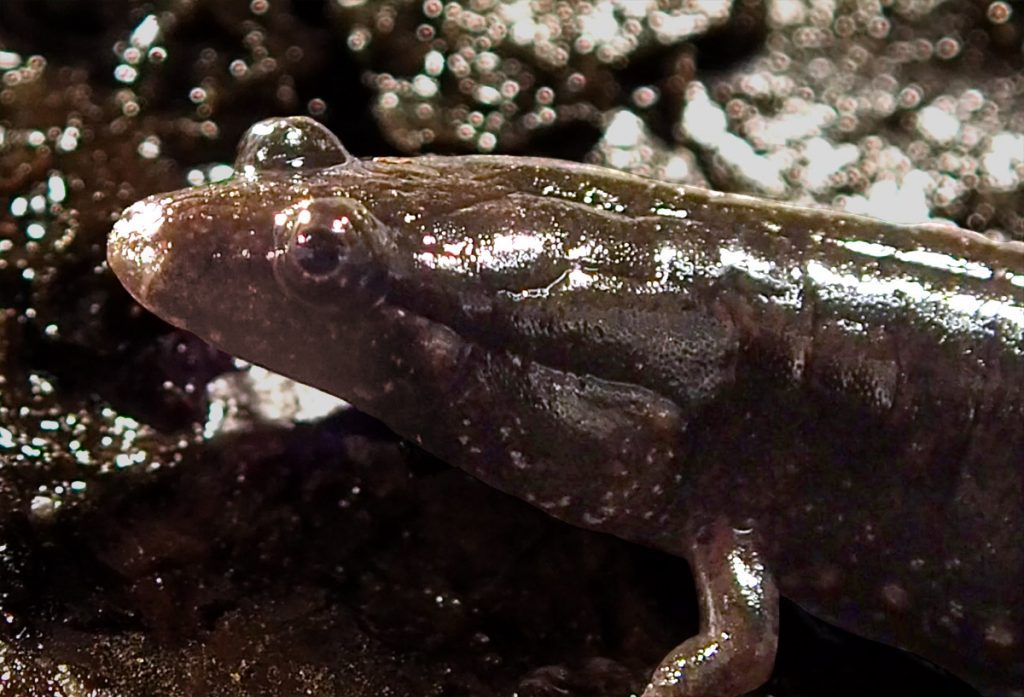

One big difference between the two duskies is their color.

On another day, we went down into a steephead ravine by the Apalachicola River. This is a much different environment than in Bradwell Bay, and one we explore in another post. Dr. Means plucked an Apalachicola dusky out from under a log.

“These are on dark muck,” he says, scooping water over it. “So their pattern is going to match the muck. If I were to catch them out on sand, you’d see a lighter pattern.”

The next week, he brought one of each dusky for us to video in the studio. While both look dark when in the muck, when cleaned up the Apalachicola dusky is brighter.

The other big difference is their tail. The Apalachicola dusky has a long, skinny tail, where the southern dusky has a “deep, blade shaped tail.” The blade shaped tail suits its habits: swimming and burrowing in muck. The Apalachicola dusky’s tail, on the other hand, is longer and skinnier. It will snap off more easily if a predator gets a hold of it. In the steephead, we found one with a tail in the process of growing back after such an encounter.

Bradwell Bay Wilderness | An Ideal Southern Dusky Salamander Habitat

These different characteristics help each animal succeed in different habitats. The Apalachicola dusky salamanders we found were in muck, but near a clear water stream with a sandy bottom. A lighter coloring would help them there.

Back here in Bradwell Bay, it’s dark. We’re standing in the shadow of titi trees, in murky water. Dr. Means is looking through dead leaves that lie atop a layer of muck. We’re looking for a brown salamander in a brown place.

“Down here where it’s swampy,” he says, “we’re not high in elevation and there’s not a lot of relief. And the water kind of ponds up, but gently and slowly moves down gradient, and forms deposits of peat with the leaf litter and twig litter and everything that’s falling from these dense titi.”

We’re in a flatter place than a steephead ravine, and water moves much more slowly here. The plants that favor this environment drop leaves that turn to mucky peat. This is where the southern dusky salamander lives. And this particular location is one of its last strongholds.

Southern dusky salamanders live at the edge of the water. During seasonal dry periods, they find shelter in fallen titi leaves, and the muck created when the leaves decompose.

The Disappearance of the Southern Dusky Salamander

Bradwell Bay is a Wilderness Area, and as such it’s one of the most protected places in the Apalachicola National Forest. At its heart is an old growth swamp with cypress, slash pine, and other trees that are hundreds of years old. Motorized equipment is banned in Wilderness areas; you can’t even bring a bicycle here.

And, as Ryan and Rebecca Means calculated, it’s the remotest spot between the Suwannee and Apalachicola Rivers. The biggest man made intrusion into Bradwell Bay is the unpaved Florida National Scenic Trail segment that runs through it.

It’s an intact swamp ecosystem. And that might be why it’s one of the few places where you can still find a southern dusky salamander.

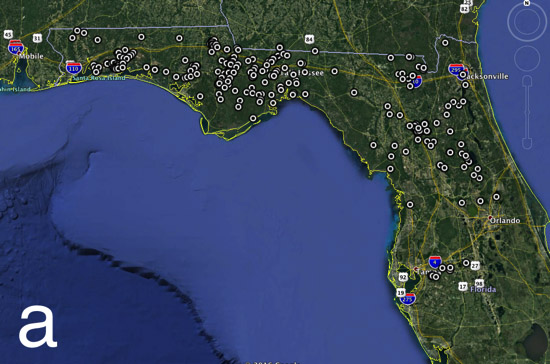

The historic range of the southern dusky salamander, based on Dr. Means sampling starting in the 1960s and 70s. Map provided by Bruce Means.

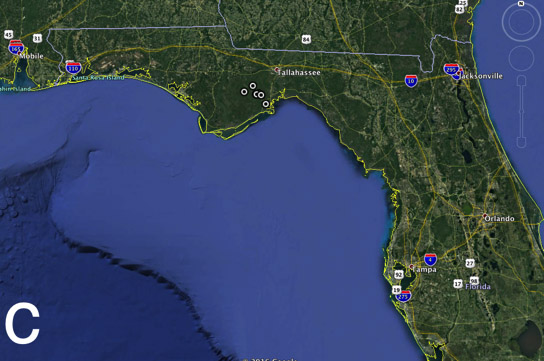

Sites where southern dusky salamanders were found in 2017. The sites on the map are all in or around the Apalachicola National Forest. Map provided by Bruce Means.

“The southern dusky salamander, for some reason unbeknownst to us, has disappeared from most of its habitats,” Dr. Means says. When doing his doctorate work, he’d found them in over 150 locations. Of the few remaining sites, many are in the Apalachicola National Forest.

He and other researchers are looking into the decline, which may be a pathogen. Whatever the cause, Bradwell Bay is remote and protected, and seems to be the best place to find southern dusky salamanders.

The Monkey Creek Swamp and the Ochlockonee River Watershed

Monkey Creek Swamp lies at the center of Bradwell Bay. It’s a headwater of the Sopchoppy River, which winds through the Apalachicola National Forest along its own nice stretch of the Florida Trail. The Sopchoppy flows into the Ochlockonee River delta and out into Ochlockonee Bay.

Ochlockonee Bay is a productive estuary fed by rivers that run through protected land. On a 2015 visit to Bald Point State Park, we saw a shrimp boat out in the bay, and fishermen casting nets in a maze of intertidal oyster reefs.

Ochlockonee Bay is a productive estuary fed by rivers that run through protected land. On a 2015 visit to Bald Point State Park, we saw a shrimp boat out in the bay, and fishermen casting nets in a maze of intertidal oyster reefs.

The seafood species owe a debt to that dark water slowly flowing through Bradwell Bay. It’s dark from decomposing plant matter, nutrient rich sludge that feeds the river and estuary system. So what’s good for the salamander can be good for mullet, shrimp, and oysters as well.

I was reminded of this connection between swamps and estuaries when Dr. Means stopped to chew on some smilax vine in Bradwell Bay. Finishing his impromptu snack, he evoked the most legendary swamp wanderer in north Florida lore: Cebe Tate.

Much of the Apalachicola River delta flows through Tate’s Hell State Forest. That colorful name comes from Tate’s misadventure in the area about 150 years ago. Last year, we heard that tale and took a deeper look at the connection between Tate’s Hell and the Apalachicola Bay estuary. Every river and bay system is different, but the post gives you an idea about how these waterways connect. And also, that protected lands protect more than just the animals and plants within them.

Leaves fall from titi trees and decompose into muck. The water is murky with plant matter. When it ultimately drains into Ochlockonee Bay, it will provide nutrients to the estuary system.

Orange trail blazes mark the Florida National Scenic Trail, usually painted onto trees. Here it’s easy to get lost in a tangle of trees, and so this blaze is painted on a post.