migratAs we await might be the last whooping crane class to winter in the St. Marks Refuge, we look back at a visit we took to the whooping crane site with Brooke Pennypacker, a dedicated crane handler with Operation Migration. We also look at the future of ultralight guided whooping crane migration, which Operation Migration is defending as they meet with partner organizations.

UPDATE – 1/25/16

This year’s ultralight guided whooping migration will be the last. Operation Migration will remain involved in the efforts to create a self-sustaining whooping crane population. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has explained the rationale behind the decision (you can read more on that below), while Operation Migration’s Brooke Pennypacker has written this touching post-decision entry to the OM field blog. From our interview with Brooke and in following Operation Migration over the last few years, I can see how invested he and the other OM staff are when it comes to whooping cranes. They have sacrificed a lot to raise, train and guide flock after flock of cranes, and I can’t imagine that they won’t continue to do so.

This year’s St. Marks flyover, likely to be this week, will be the last. A number of cranes have continued to migrate back to the Refuge after their initial migration, and under the new management regime, the hope is that they will be the ones to guide captive-raised chicks south for the first time. It will be years before the new practices can be judged to be successful, and even then, as in the case of ultralight guided migration, the results may not conclusively predict the long term success of the population. All I can with certainty at this point is that I know there will be dedicated people working their hardest to make it work.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

When I met Brooke Pennypacker, he brought with him an example of the many challenges faced by a whooping crane handler. The staff at the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge visitor center told us that Brooke was busy handling an issue in the crane pen, and that he’d be late. About 30 minutes later, he pulled up in an Operation Migration pickup truck. In the bed was a bundle of plastic fencing and white cloth from which an alligator tail protruded. Brooke had recently noticed the cranes move from their usual roosting spot, next to an oyster bar, to a spot on the other end of the pen. They were acting spooked. After spotting the young gator, he borrowed a seine net from Jack Rudloe at the Gulf Specimen Marine Lab, caught it, and wrapped it in his whooping crane feeding costume. All in a day’s job.

This young alligator found its way inside of the St. Marks Wildlife Refuge whooping crane pen. Alerted to its presence by spooked cranes, Brooke Pennypacker removed it and wrapped it in his whooping crane feeding costume.

I visited the crane pen in 2014 during the process of finishing the Oyster Doctors documentary. I wanted to close the show out with shots that illustrated the importance of salt marsh, oyster reef, and seagrass bed ecosystems, and I wanted them to span Florida’s Forgotten Coast. Scalloping in Saint Joseph Bay (seagrass). Oystermen in Apalachicola Bay. Whooping cranes in salt marshes on the Refuge. If these cranes are ever going to shed their endangered status, they’ll need healthy estuarine marsh habitat featured in the show. I got the shot I needed, but I’ve only just revisited the rest of the footage and interviews we got that day for the video you see above. I wanted to get it to air as the cranes were close to arriving.

A lot of work goes into raising and guiding the cranes from fresh water marshes in Wisconsin, and Brooke is there at every step. From the time they hatch at the Patuxent National Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, Brooke is there to feed and train them. Flight training begins in Necedah National Wildlife Refuge after the cranes are 50-60 days old. In the fall, when the cranes are old enough, Brooke is one of the pilots flying them down in ultralight planes, or “trykes” (kind of like large motorized tricycles with wings).

That migration happens over several short hops, as the trykes’ fuel supply doesn’t carry them far. High winds or fog can easily ground the small aircraft at any number of the stops, and so it can be difficult to predict their arrival. They’ve gotten here as early as November (a two month journey), but in other years, it’s taken until January. As I’m writing this, they’re laid up in Georgia until at least the 24th, potentially making this their longest migration. Operation Migration blogs their trip down, and you can follow their progress on a Google map. It can be fun and frustrating to follow, and kind of addicting.

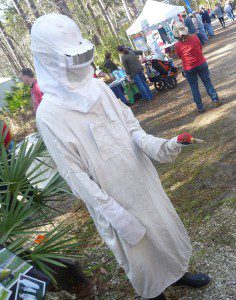

Once at the St. Marks Refuge, Brooke looks over the cranes from a blind located about a quarter mile from their pen. By the time they depart, on their own, Brooke will have been with the cranes for almost a year. They’ll never have seen his face. To prevent cranes from being habituated to humans, crane handlers wear white, featureless suits with a whooping crane dummy on the hand. Within a couple of months, the process begins anew. Brooke has been at it since joining Operation Migration in 2002, but that may all end this year. After the cranes fly north in the spring, there may not be a new ultralight class.

The Future of Guided Whooping Crane Migrations

In the video, Brooke mentions a black fly infestation scaring whooping crane parents off of nests in Necedah. Black flies are the largest reason that the Eastern Migratory Population has had little success breeding in the wild, and it may cause a shift away from ultralight guided migrations.

The Eastern Migration Population (EMP) was created through the efforts of the Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership, a coalition of non-profit organizations and government agencies that includes Operation Migration and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The EMP was intended to be a second self-sustaining whooping crane population that would supplement the primary Aransas Wood Buffalo Population. The centerpiece of the effort to date has been the guided migration of cranes by Operation Migration. The cranes are raised in captivity and guided to Florida by ultralight planes, from where they return on their own. The hope is that they would continue to migrate on their own, hatch and care for new generations of birds, and teach their offspring to migrate. Achieving this is part of the EMP being considered a self-sustaining population. Fifteen years after the first ultralight guided migration, however, the USFWS is uncertain that the goal can be achieved using the current strategy.

Specifically, the USFWS is recommending the abandonment of guided migration in favor of an alternative method of releasing cranes called Direct Autumn Release. In an eight page vision statement released in October 2015, the Service sites the “population’s low reproductive success (i.e., hatching and fledging of young)” as the primary factor keeping the population from being self-sustaining. Since 2001, about 250 cranes have been introduced into this population (about 180 in guided migrations), with 93 adults having survived. The population has hatched at least 63 colts; seven have survived to fledge and two are still alive and have successfully nested (page 1 of the PDF. Operation Migration used a wider data set in which 9 birds have fledged). Two-hundred and fifty released cranes have only successfully produced two adult cranes in the wild, and the reason is black flies in the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge. So, what do black flies have to do with ultralight airplanes?

According to the USFWS, “Captive-reared whooping cranes may not possess the behaviors required to tolerate biting insects.” (Page 4) Perhaps, their reasoning goes, the captive-raised birds have been sheltered from flies and other pests, and when faced with them, too easily abandon their nests. Their theory is that the current system of raising chicks is too artificial, and that their instincts have not fully developed as a result.

An Operation Migration member shows off the whooping crane feeding costume at the St. Marks Wildlife and Heritage Outdoors (WHO) Festival. The US Fish and Wildlife Service theorizes that costumed handlers and ultralight training have inhibited the instincts of whooping cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population, leaving them unable to survive without human assistance. Operation Migration refutes this claim.

USFWS is calling for limiting exposure to costumed humans. While lauding Operation Migration’s “novel reintroduction methods,” as well as their success engaging communities and educating thousands of people, USFWS believes that “Ultralight-led rearing and release is more artificial and costly than any other currently used release method and does not appear to yield substantially better results.” (7) In other words, a less artificial means of raising birds might make them tougher against predators and pests. The document goes on to say that the Service values Operation Migration’s efforts, and it looks forward to working with them using new strategies.

Operation Migration has responded that previous Direct Autumn Release (DAR) birds have had lower survival and nesting rates than ultralight birds, and that the method hasn’t been tested extensively enough to gauge its efficacy. DAR minimizes cranes’ exposure to humans, with the expectation that adults in the EMP will guide the DAR juveniles south in the winter. Operation Migration argues that DAR releases birds earlier than when they would naturally become independent. DAR chicks were released in the Horicon Marsh National Wildlife Refuge, where only two adult whooping cranes had returned. The adults took no interest in the chicks, who instead bonded with sandhill cranes. One of the DAR cranes mated with a sandhill to create a “whoophill” hybrid. Operation Migration also points out that the 2013 DAR cohort did not migrate properly and that many individuals died in the cold.

Another point of contention is the data set that the USFWS used to determine the efficacy of ultralight migration. The worst black fly problems occurred at the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge, where all three species of black fly that attack cranes can be found. In 2011, Operation Migration moved their release point to Horicon and the White River Fisheries Area, with the hopes that the birds would return there to nest. The data used to create the USFWS vision statement ends in 2010. Operation Migration notes that whooping cranes can take five years to reach sexual maturity, and that another couple of years will be needed to see whether the classes released in recent years can nest successfully.

Large crowds gather annually in this field by the St. Marks River to witness whooping cranes fly over. With just over twenty stops on the migration, communities along the path have become engaged and educated about the efforts to restore whooping crane numbers. Those who can’t go and see the birds can follow on the Operation Migration web site.

Lastly, Operation Migration takes exception to the USFWS claim that their method is too costly, as they privately raise funds to cover their costs. “To complain about the cost of that gift is ungrateful.”

The USFWS controls the eggs and the land on both sides of the migration path, which gives their recommendations weight. However, nothing has been definitively decided. The members of the Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership have been meeting over the last couple of days (January 20-21) to discuss and come to an agreement on what path best leads to a population of whooping cranes that survives without human aid. Additional strategies will also be discussed, including measures to reduce black flies In Necedah, but the continuation of guided migrations will be the most hotly debated. I’ll update this post after the meeting.

What Becomes of the Broken Hearted?

The single crane seen among Canada Geese in the video is known as 11-09, a male from the 2009 St. Marks class. In the 2011 through 2014 migrations, 11-09 and a female, 11-15, had migrated together to a cow pond in Leon County after having previously returned with their cohort to St. Marks. Sadly, 11-15 has since taken up with another male, leaving 11-09 to migrate alone for the 2015 season.

More in reintroduced species: The Striped Newt

When a species disappears from a geographic region, it’s called extirpation. For example, whooping cranes used to winter from Chesapeake Bay to the north of Mexico. When, the 1940s, their population shrank to 20 or so individuals in Texas, they were extirpated from most of their range. Even though the numbers of that naturally occurring population have improved, having them confined to a smaller region leaves them vulnerable as a species. That’s why the establishment of a second population was seen as a means to further safeguard the future of whooping cranes.

Whooping cranes are an iconic symbol of efforts to rehabilitate species that have been widely extirpated from their range, but they are far from the only ones. Recently, we accompanied Ryan and Rebecca Means of the Coastal Plains Institute, as well as Pierson Hill of Florida Fish and Wildlife and a group of young volunteers, as they released striped newts into ephemeral wetlands in the Apalachicola National Forest. During an extended drought event, these ponds went dry and the newts disappeared. Currently, the only place they are found in the wild is a wetland in southwest Georgia. The newts released were raised in captivity at the Jacksonville Zoo.

We’ll have that video in the next month or two, as well as a response by professional archeologists to a bill that would allow amateur collection of artifacts in Florida, and of course our 10-part journey through the Red Hills of Florida and Georgia.

Come adventure with us in the Red Hills, Apalachicola River and Bay, St. Marks Refuge, and More! Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog by Email.

His hands steadied by CPI Director Ryan Means, my son Max holds a pair of striped newts. Every male was released with a female in the hopes that they would mate and create new generations of newts in the Apalachicola National Forest. As with whooping cranes, successful breeding in the wild is critical if a population is to be self-sustaining.