In January, David Kimbro’s lab did a preliminary survey of Apalachicola Bay oyster reefs, looking at the overall health of oysters and the presence of predators. They followed this up with an experiment meant to monitor oyster health and predator effects over time. Many of their experimental cages were displaced, likely due to the buoys marking them breaking off. But what they found in the cages that remained intact was that oyster drill numbers appear to be exploding in warmer waters. David is looking for help keeping tabs on them.

Dr. David Kimbro Northeastern University/ FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Wishing that you were wrong is not something that comes naturally to anyone. But that is how I felt at the most recent oyster task force meeting in April. There, I shared some early research results about the condition of the oyster reefs. In our surveys, we found that the oyster reefs in Apalachicola Bay were in really bad shape and that there were not any big bad predators hanging around the reefs to blame. Even though I had originally shot off my big mouth about the oyster fishery problem being caused by an oyster-eating snail, I hoped that our first bit of data meant the snails were never there. Or better…that they were gone. The story of the boy who cried wolf comes to mind.

But an alternative of this David-cries-wolf story is that our January sampling didn’t turn up many predators because it’s cold in January, and because they were hunkered down for a long winters nap. Unfortunately, this option is looking stronger.

Since the task force meeting, we have been figuring out how conduct field experiments in Apalachicola. To be honest, an underwater environment without any visibility is an experimentalist’s worst nightmare. Still, we deployed fancy equipment, big cages, and then little mini experiments inside each big cage to figure out how much of the oyster problem is due to the environment, to disease, or to predators.

Even though we lost over half of our experiment and instrumentation, we recovered just enough data to show that the problem could be predation and that the culprit is a voracious snail. So, after learning some lessons on how to not lose your equipment, we decided to take another crack at it. In fact, Hanna and crew just finished sampling half of our second experiment today. We got the same results….lots of snails quickly gobbled up all of the oysters that were deployed without protective cages. But the oysters that were protected with cages did just fine.

This photo illustrates what Apalachicola oyster reefs are dealing with. This is one clutch of eggs laid by one adult snail. Within each little capsule, there are probably 10-20 baby snails. After a long winter’s nap, these snails are hungry.

We are going to keep at this, because one week long experiment doesn’t really tell us that much. But if we keep getting the same answer from multiple experiments, then we are getting somewhere.

In addition to updating y’all, I wanted to ask for your help. Because my small lab can’t be everywhere throughout the bay at all times, there are two things you could do if you are on the water.

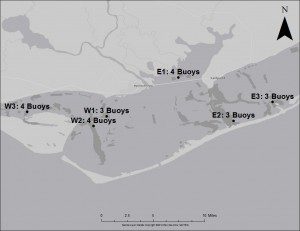

First, if you come upon our experiment, can you let me know when you happened upon them and how many buoys you saw? If you report that all buoys are present, then I’ll sleep really well. And if you alert us that some buoys are missing, then I’ll be grateful because we will stand a better of chance of quickly getting out there before the cages are inadvertently knocked around, so that we can recover the data. Click here for GPS coordinates and further instructions.

Second, if you are tonging oysters, then you are probably tonging up snails. It would really help us to know when, where, and how many snails you caught. Take a photo on your phone (Instagram hashtag #apalachcatch – Instagram instructions here) or e-mail them to robdv@wfsu.org. We’ll be posting the photos and the information you provide on this blog.

This is kind of a new thing for us, attempting to use technology and community support this way. There may be some bumps along the way. If you’re having trouble trying to get photos to us, contact us at robdv@wfsu.org.

Thanks a bunch!

David

David’s Apalachicola Research is funded by Florida Sea Grant

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.