A couple of years ago, David wrote about what seemed to be a very locally contained problem. An out of control population of crown conchs was decimating oyster reefs south of Saint Augustine. Now, he’s seeing that problem in other Florida reefs, including those at the edges Apalachicola Bay. In reviewing his crew’s initial sampling of the bay, he sees that the more heavily harvested subtidal reefs are being assaulted by a different snail.

Dr. David Kimbro FSU Coastal & Marine Lab

Along the Matanzas River south of St. Augustine Florida, Phil Cubbedge followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather by harvesting and selling oysters for a living. But this reliable income became unreliable and non-existent sometime around 2005. Then, Phil could find oysters but only oysters that were too small for harvest. Like many other folks in this area, Phil abandoned this honest and traditional line of work.

Along the Matanzas River south of St. Augustine Florida, Phil Cubbedge followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather by harvesting and selling oysters for a living. But this reliable income became unreliable and non-existent sometime around 2005. Then, Phil could find oysters but only oysters that were too small for harvest. Like many other folks in this area, Phil abandoned this honest and traditional line of work.

In 2010, Phil was fishing with his grandson along the Matanzas River and spotted several individuals who seemed severely out of place. Because Phil decided to see what they were up to, we are one step closer toward figuring out what happened to the oyster reefs of Matanzas and what may be happening to the oyster reefs of Apalachicola Bay.

Before I met Phil on this fateful morning, I was studying how the predators that visit oyster reefs may help maintain reefs and the services they provide (check out that post here). My ivory-tower mission was to see if the benefits of predators on oyster reefs change from North Carolina to Florida. To be honest, I’m not from Florida and I blindly chose the Matanzas reefs to be one of my many study sites. And in order to study lots of sites from NC to Florida, I couldn’t devote much time or concern to any one particular site. In short, I was a Lorax with a Grinch-sized heart that was two sizes too small; I just wanted some data from as many sites as possible.

Hanna Garland (r) discusses with Cristina Martinez (l) how they will set up gill nets as part of their initial oyster reef research in St. Augustine.

But then I met Phil, heard about his loss, and understood that no one was paying attention to it. After looking around this area, my Grinch-sized heart grew a little bigger. Everywhere I looked had a lot of reef structure yet no living oysters. Being a desk-jockey now, I immediately made my first graduate student (Hanna) survey every inch of oyster reef along 15 km of Matanzas shoreline. I think it was about a month’s worth of hard labor during a really hot summer, but she’s tough. Hey, I worked hard on my keyboard!

With these data and lots of experiments, we showed that a large loss of Matanzas oyster reef is due to a voracious predatory snail (crown conch, Melongena corona). This species has been around a long time and it is really important for the health of salt marshes and oyster reefs (in next week’s post, Randall shows the crown conch’s role in the salt marsh). But something is out of whack in Matanzas because its numbers seemed to look more like an outbreak. But, why? Well, thanks to many more Hanna surveys and experiments, we are closing in on that answer: a prolonged drought, decreasing inputs of fresh water, and increasing water salinity.

David took an exploratory trip to Apalachicola Bay with the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services in the fall of 2012, where they found these snails.

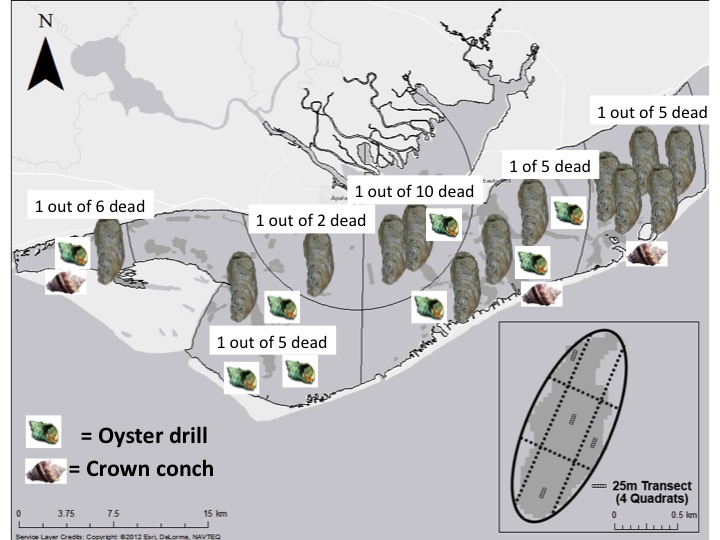

We need to figure this out soon, because we see the same pattern south of Matanzas at Cape Canaveral. In addition, I saw conchs overwhelming the intertidal reefs of Apalachicola last fall. While these reefs may not be good for harvesting, they are surely tied to the health of the subtidal reefs that have been the backbone of the Apalachicola fishery for a very long time. Even worse, the bay’s subtidal reefs seemed infested with another snail predator, the southern oyster drill (Stramonita haemastoma). Is this all related? After all, according to locals and a squinty-eyed look at Apalachicola oyster landings, it looks like Apalachicola reefs also started to head south in 2005.

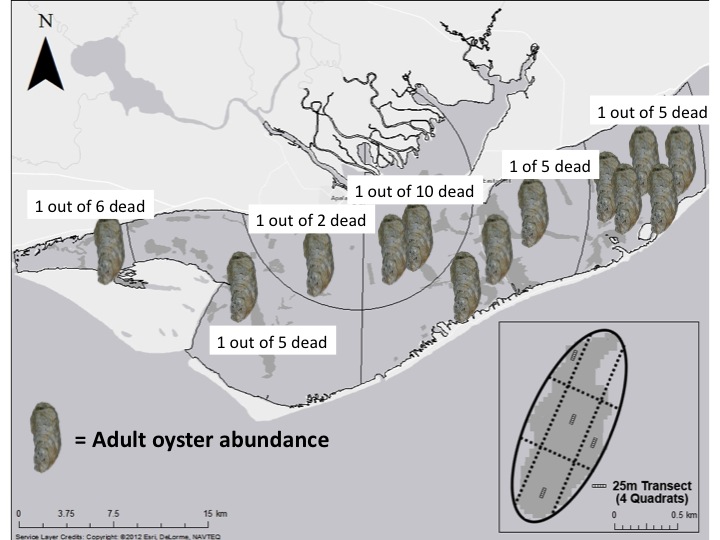

To help answer my question, my team began phase 1 of a major monitoring program throughout Apalachicola Bay in January 2013.With funding from Florida SeaGrant, my lab targeted a few oyster reefs and did so in a way that would provide a decent snap shot of oysters throughout the whole bay. With the help of Shawn Hartsfield and his trusty boat, a visit to these sites over a time span of two weeks and hours upon hours of sample processing back at the lab revealed the following:

(1) There is a lot more oyster reef material in the eastern portion of the bay;

(2) There are also a lot more adult oysters toward the east;

(3) Regardless of huge differences in adult oyster density and reef structure, the ratio of dead oysters to live oysters is about the same throughout the whole bay;

(4) Although the abundance of snail predators is not equal throughout the whole bay, it looks like their abundance may track the abundance of adult oysters.

(4) Although the abundance of snail predators is not equal throughout the whole bay, it looks like their abundance may track the abundance of adult oysters.

These data do not show a smoking gun, because many different things or a combination of things could explain these patterns. To figure out whether the outbreak of multiple snail predators is the last straw on the camel’s back for Apalachicola and other north Florida estuaries, we are using the same experimental techniques that Hanna used in Matanazas River. Well, like any repeat of an experiment, we had to add a twist. Thank goodness Stephanie knows how to weld!

Luckily, I have a great crew that is daily working more hours than a day should contain. As I type, they are installing instrumentation and experiments that will address my question. If you see Hanna and Stephanie out on the bay, please give them a smile and a pat on the back.

More later,

David

Click here to see graphs illustrating the increase in salinity in the Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR). The NERR System allows you to review data from sensors at any of their reserves, including Matanzas and Apalachicola.

Music in the piece by Philippe Mangold.

In the Grass, On the Reef is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

9 comments

Any boring sponge with the increase in salinity at your sites?

hi John,

thanks for your question. We are still working up those data. But boring sponge certainly loves elevated salinity, so I expect to see a bunch of it. A really good scientist up at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Niels Lindquist; http://ims.unc.edu/home/people/lindquist/) studies this scenario. From the results I’ve seen out of his lab, boring sponges can have huge effects on oyster reefs. So, your question is right on the mark.

Best,

David

[…] Donate Skip to content HomeThe ScienceThe “In the Grass, On the Reef” Master PlanCoastal Habitat Quick DictionarySalt MarshIn the Grass- Salt Marsh Biodiversity StudyMeet the Species “In the Grass”Oyster ReefOn the Reef- The Biogeographic Oyster StudyMeet the Species “On (and swimming around) the Reef”Watch Oysters GrowJacksonvilleSaint AugustineAlligator HarborSeagrass BedPredatory Snails, and Prey, of Bay Mouth BarIn the Grass, On the Reef DocumentaryEcoAdventures North FloridaEcoAdventures HomeActivitiesPaddlingHikingBird/ Wildlife WatchingArt/ PhotographyHistory/ ArcheologyApalachicola River and Bay Basin ← Predatory Snails Overrunning Florida Oyster Reefs […]

[…] […]

[…] you’re a fan of oysters and you read David’s previous post, then you probably don’t like crown conchs very much. Why? Because David and Hanna’s […]

[…] When they die, their shells open permanently). You can read a brief summary of his results here. Hanna is currently deploying an experiment featuring live oysters and spat tiles (watch a video […]

[…] forget about the conchs that are eating away at oyster reefs in St. Augustine, Florida and may be doing the same to those in […]

[…] the oysters themselves as well as the resident crustacean and invertebrate species. We found some interesting patterns, but this survey data is just a “snapshot” in time of the oyster reef communities, so we […]

[…] the National Weather Service correlate warm episodes with events Randall and David care about: the ruining of oyster reefs south of Saint Augustine by crown conchs in 2005, the Apalachicola oyster fishery crash last year, […]

Comments are closed.