Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

I like the idea of hiking cross country, unimpeded, for miles at a time. Trails are great, of course. But they only offer up so many possibilities. What if you could stand in one place, look in every direction, and just go where it looked most interesting?

I like the idea of hiking cross country, unimpeded, for miles at a time. Trails are great, of course. But they only offer up so many possibilities. What if you could stand in one place, look in every direction, and just go where it looked most interesting?

On our hike through the St. Joseph Bay Buffer Preserve, Dr. Jean Huffman is leading us on just such an adventure to look for rare plants. The showiest of those is Chapman’s rhododendron. This is the only public land where this flowering shrub is found. Other unique-to-Florida (or unique-to-the -panhandle) species are hidden within the grass.

Fire creates this open landscape, eliminating woody oaks and titi that would otherwise crowd out hundreds of grasses, flowers, and other succulent plants that thrive in this ecosystem.

The grass also hides something else that has considerable ecological value. As Jean tells us, this is one of the few places with old growth longleaf pine stumps. Like a lot of what is now managed longleaf habitat, this used to be timber land. Typically, stumps would have been sold along with the trees. Here, however, are stumps from trees that date back hundreds of years.

So why are these stumps important? They help Jean in her research. They can tell her how often this forest had burned before Europeans arrived in Florida. This in turn will tell us how often this forest should be burned, if we want the ecosystem to support the diversity of plants and animals that it’s known for.

We’ll look at that research in a minute. First, let’s take a peek in the grass and see some of that diversity, with some great photos by production assistant Alex Saunders.

Rare Flowers of the St. Joseph Bay Buffer Preserve

Our first destination of the day was a cluster of Chapman’s rhododendron (Rhododendron chapmanii) bushes:

Chapman rhododendron (Rhododendron chapmanii) bushes at the Saint Joseph Bay Buffer Preserve in north Florida.

This flower is endemic to about four Florida counties. And the Buffer is the only public place where you can view this flower. It typically blooms in late March/ early April. But, like any seasonally dependent blooming flower, that range changes depending on the warmth of the winter and subsequent spring.

Deeper in the grass, we find a plant endemic to three Florida coastal counties- Telephus spurge (Euphorbia telephioides):

Again, this is the only public land where you can find this plant. This is a fire dependent plant only found within four miles of the coast in Bay, Gulf, and Franklin counties.

And yet another panhandle endemic species, Chapman’s crownbeard (Verbesina aristata). Dr. Alvin Chapman was an Apalachicola based botanist who discovered many rare plant species.

We find many species here typical of the transitional areas between pine flatwoods and wetter areas. This means a lot of carnivorous plants and orchids, such as this bearded grass pink orchid (Calopogon barbatus):

One carnivorous plant we found was Chapman’s butterwort (Pinguicula planifolia). This is a threatened species within our state:

Another carnivorous plant is the oblong leaved sundew (Drosera intermedia). Here, Alex racked the focus on his camera to see the flower, where bees can safely pollinate the plant, and the sticky leaves at the bottom, where the plant traps and consumes bugs.

The friends of the Saint Joseph Bay Preserves maintain a full list of plant species found around the bay.

The Fire History of a Forest- Read Through Its Tree Rings

So, how often did forests burn before European settlement of Florida? It turns out that trees have the answers in their rings. We get a glimpse of this towards the end of the video above, but I wanted to take a closer look at how Dr. Jean Huffman was able to interpret the data locked within trees.

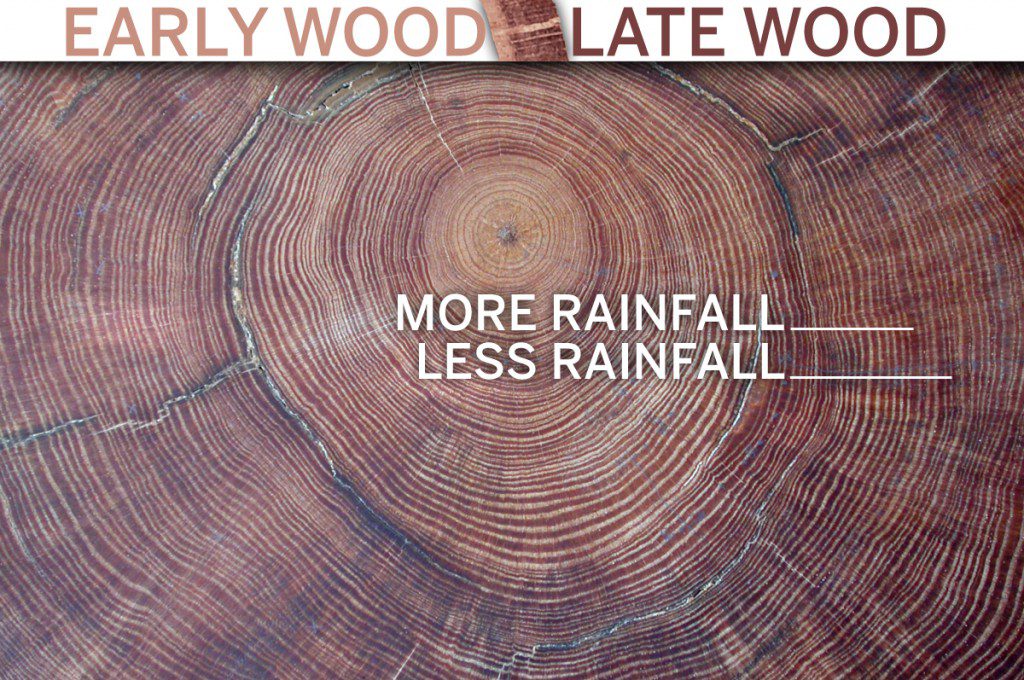

The photo above is a cross section of a longleaf pine (Pinus palustrus) stump. In it you can see that the rings alternate in shading between light and dark. The light wood is early wood. This is from the beginning of the growing season, typically spring, when a tree usually grows the fastest. The growth in the summer and fall is darker, and is called late wood. Winter is the dormant season.

So one light and one dark ring equal one year of growth for the tree. You may also notice that some rings are wider than others. Wide rings indicate a higher rainfall, and especially narrow rings indicate drought. Knowing this, we can start building a master chronology.

Jean creates a master chronology by comparing the relative width of rings in a series of trees. In this way she can date rings in each tree exactly, even if there are occasional missing rings or false rings in an individual tree. The master chronology can be used to exactly date the rings in individual stumps.

Since longleaf pine is such a long-lived species, they store potentially hundreds of years’ worth of climatological data in its rings. When you have data for many trees, they can tell a story that goes back before people started keeping records. This is a dendrochronology (dendro= tree, chronology= matching events to specific dates based on historical records).

Finally, Jean matches years in the chronology to fire scars (that’s a scar to the left). Longleaf pine are a fire resistant species, and it takes a lot to kill the cambium and create a scar. Because of this, Jean only created fire histories for periods when she had at least three “recorder” trees- enough to establish a pattern.

Finally, Jean matches years in the chronology to fire scars (that’s a scar to the left). Longleaf pine are a fire resistant species, and it takes a lot to kill the cambium and create a scar. Because of this, Jean only created fire histories for periods when she had at least three “recorder” trees- enough to establish a pattern.

She determined that there were frequent fires in the area- every one to three years. That’s enough to keep oak and other woody plants from encroaching on ground cover plants, including the many rare plants of the SJB State Buffer Preserve.

The video features music by Pitx and Airtone. Thanks to Dr. Jean Huffman for reviewing my text for accuracy.

Next on EcoAdventures North Florida, we’re going to a place where large chunks of land get swallowed up by the earth, and where a river goes underground. Of course we mean Aucilla Sinks (Wednesday April 11 at 7:30 PM/ ET on WFSU-TV’s dimensions).