VIDEO: “Turtle” Bob Walker and his dog Al lead us through longleaf forests and a steephead ravine on Nokuse Plantation.

Wandering through a sandhill looking for gopher tortoises, “Turtle” Bob Walker spots a young longleaf pine. This tree is in its bottlebrush stage, a knee-high teenager getting ready to bolt. Unlike Walker or I, it could very well witness the entirety of the 300-year plan here at Nokuse Plantation. It likely first sprouted during Nokuse’s first habitat restorations in the early 2000s; in 2300, it might have grown to be a grandfather tree in an (almost) old growth forest.

The three hundred year plan was M.C. Davis’s vision. After making a living as a gambler in his 20s, Davis turned his winnings into hundreds of millions of dollars buying land and mineral rights. Then, one day, he stumbled into a rally for black bears in Florida. Learning about bears led to his devouring books on ecology and Florida habitats. He caught the conservation bug, and starting in 2000, he spent $90 million on land for a private preserve along the Choctawhatchee River.

Restoring and managing 55,000 acres of private land is an ambitious undertaking. A majority of the property was once timber land that Nokuse is returning to native longleaf pine ecosystems. As we’ll see on our adventure today, there are also wetlands and waterways here; these would benefit from regularly burned pinelands.

But back to the size of the property. In winter of 2019, we visited Torreya State Park, where a 4,600 acre restoration has been underway for about as long as Nokuse’s. They’re still methodically working their way through that restoration, 300 acres at a time. Transforming a property several times larger- well, it’s no quick task.

And neither is exploring it. Luckily, our guides have selected a few highlights.

Nokuse Plantation at a Glance

- Nokuse Plantation is a private preserve, but about 27 miles of the Florida National Scenic Trail runs through the plantation. The trail passes through sections of Nokuse in different states of habitat restoration. In 2017, we hiked this trail section shortly after the construction of a boardwalk through a cypress swamp on the Choctawhatchee River section.

- For more information on hiking and camping, visit the Florida Hikes pages for each of the three trail segments on the property:

- Nokuse also operates the EO Wilson Biophelia Center, an educational facility focused on north Florida ecosystems.

1. Young Gopher Tortoises in the Sandhills

We have two guides today. One is Bob Walker, Nokuse Plantation’s gopher tortoise biologist. The other is his dog, Albert Einstein. Why don’t I have more dogs in my videos?

Our first stop is, unsurprisingly, a section of restored sandhill where gopher tortoises had been relocated. Sandhills are longleaf habitats on sandy soils that don’t hold water for long. As a result, the understory plants in a sandhill are adapted to making do with not so much water.

Prescribed burns every two to three years keep woody shrubs, such as turkey oaks, from clogging the space between the pines. This creates open space for tortoises to make their burrows, and for the herbaceous plants they eat.

The setting is right. We find tortoise favorites such as gopher apple, milkpea, blueberries, and wiregrass. We also see pollinator plants such as soft greeneyes and slimleaf paw paw, the larval food of the zebra swallowtail butterfly. We’ll take a closer look at the plants we found here below.

Their food is here, but we’re not finding any evidence of the tortoises that were relocated here. But we are finding some burrows.

The difficulty of relocating adult gopher tortoises, and hope

“This tortoise is about this size,” Walker says, holding his fingers a few inches apart above a small burrow, “which means that it’s a sub-adult. It’s not even an adult yet.”

We see this sub-adult burrow, and then one for a smaller juvenile. Gopher tortoises make burrows that are just big enough for them to turn around. The size of the burrow tells us the size of the tortoise. So, while we aren’t seeing the adults that were introduced here, there is hope.

“They’re very difficult to relocate, so if they’re not in that perfect spot they want to be, they will leave.” Walker says. “They’ll find another area. And in this case, they laid eggs before they left. And the coyotes and the raccoons did not find them, and we had some actual success with the regeneration of the tortoises here.”

We’ve previously covered different animal reintroduction projects on the blog, such as striped newts and indigo snakes. It can take several years of releases for enough animals to survive predators, make homes for themselves, and find mates to breed. And then to, ultimately, have generations of breeding, creating a self sustaining population.

The gopher tortoise adults introduced here may not have stuck around, but having tortoises conceived and born here is a good sign.

2a. Partially Restored Habitat Shows Promising Signs

Our next stop is not in the video, and it wasn’t on our schedule for the day. But, on the way to our second spot, Walker sees a nice sandhills milkweed specimen, and here we are. We’d been passing plots in different stages of restoration; this particular section had been a sand pine plantation. Sand pines are Florida natives, but this isn’t their natural setting.

Nokuse had clear cut the sand pines, but hasn’t introduced fire here yet. Even without fire, though, we see a species at home in a regularly burned sandhills habitat.

This is a transitional, incomplete ecosystem. And yet, we see how life has adapted here. Nearby, Walker finds another staple sandhill species- the Florida harvester ant. Harvesters usually decorate their nests with charred bits of pine needle. Without fire, however, these ants have found other bits of material to adorn their mounds.

Walker spots another sign of life.

“Here’s an old field mouse burrow,” he says. “This is one of end of it here. And you can see that little apron from all that sand they kick out.” Gopher tortoise burrows have aprons as well; a clean apron is one indication that a tortoise is moving in and out, and that the burrow is active.

A few feet away, we find a second entrance. “If they’re down in there and a snake comes in, they can zip out the other end.”

2. Down into a Nokuse Steephead Ravine

One more stop before our destination- Turtle Bob wants to check out a creek. In it, he finds the yellow-bellied slider we see in the video (with that cool leech attached to it).

Our destination is another wetland area. Steephead ravines are a uniquely Floridian phenomenon- on Earth, anyway. Last year, we explored a couple of steepheads on the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve (ABRP). There, we learned how water filters through sand in deep sandhills, accumulating on the rock layer below. From there, trickles start seeping out along river bluffs, eventually carving out steep, narrow, shaded ravines.

We also learned that fire can affect how much water flows downwards. If those small turkey oaks between the pines aren’t burned back, they become full sized, thirsty trees. And they intercept more of that water before it percolates down through the sand.

The first step to entering a steephead is finding an opening where the slope below is both clear of obstacles and not overly steep. This is a smaller steephead, and the angle of the slope isn’t too extreme. We stroll right in.

When we get to the bottom, Al takes off and splashes through the stream. Steephead streams seep from the head of the ravine, cool, clear water moving swiftly over a sandy bottom. I bet it feels nice on dog paws, even if the humans have decided to wear boots.

Where are all the snakes?

As with all steephead streams, this one is lined with Florida anise. Hardwoods shade the stream and the slope. Because of the narrowness of the ravine, the trees up top keep sun from directly hitting the ravine bottom. Among those hardwoods are a couple of impressive southern magnolias, one of which has fallen across the stream.

Steepheads are always expanding, in geologic time. Occasionally, that slow movement of the slope loosens the soil around tree roots, and the trees come down. This one appears to still be alive.

Walker stops occasionally to move over a log, or plunge his hand into a muddy spot. There should be a wealth of amphibians here, but we’re not finding any. Or any snakes.

“What a perfect place for a cottonmouth just to hang out, you know?” Walker says. “It really is. It’s beautiful in here, just incredible. And they have decided to hide.”

These are animals good at hiding, even if Walker is experienced in finding them.

But it occurs to me, the area around the ravine is still in need of restoration. Some snake species move in and out of ravines to forage or seek shelter in the uplands. In the coming decades, the land will transform and gopher tortoises will make burrows that will shelter both snakes and their prey species. There will be more to eat around the ravine, meaning more animals both in and above it.

3. Pitcher Plants on the Seepage Slope

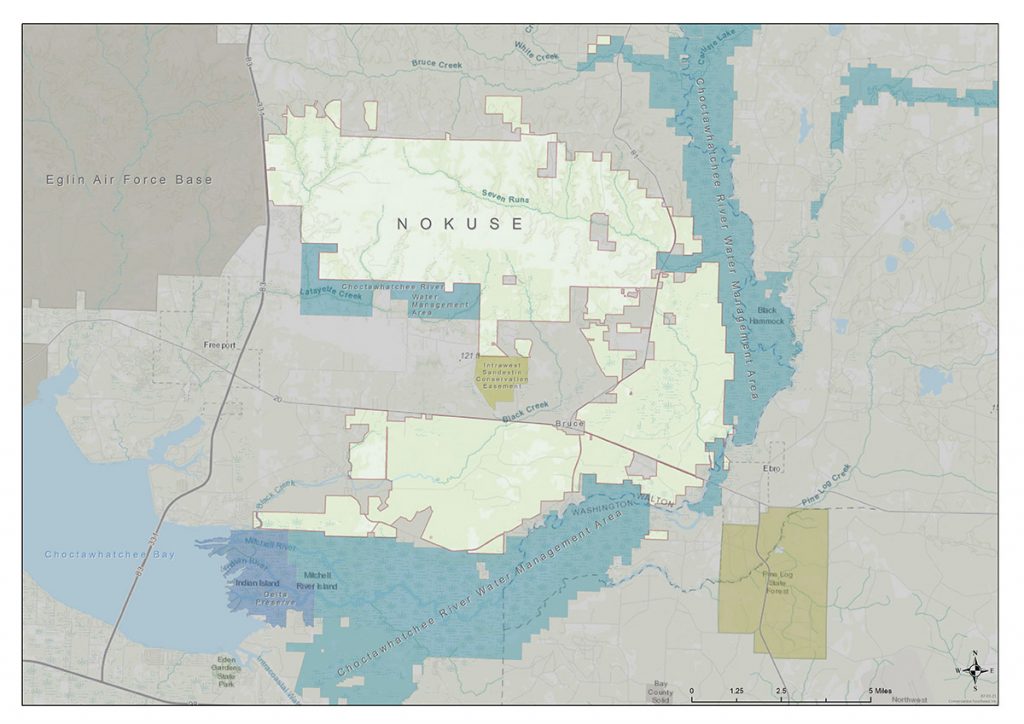

We take another long drive on the way to the next location. Nokuse Plantation covers a lot of acreage, much of which is accessible by networks of dirt roads. The property is also arranged in kind of a “c” formation, so we hit state road 81 to travel between parcels of land.

The odd shape of the combined land purchases makes it so that Nokuse connects several pieces of public land along the Choctawhatchee and over to Eglin Air Force Base, which has its own steephead ravines as well as old growth longleaf ecosystems.

Our final stop is a seepage slope. The water that moistens the ground here is similar to that in the steephead. In much of Florida, water sinks down into a porous limestone aquifer; but where rock is less porous, water pools atop it. Instead of forming large springs, these smaller surficial aquifers seep.

Here, we’re walking in an open longleaf/ wiregrass habitat, like in a sandhill. A fire dependent habitat. But the seepage makes the ground moist, and so we see some different plants in the understory. The pines are more widely spaced, and between them we see pitcher plants as far as the eye can see.

“What’s amazing, too, is that at one time, this went on much farther,” Walker says, estimating that the current area covered with pitcher plants is about 100 acres. “The landowners cleared it and planted in slash pine.”

The Future- an Old Growth Longleaf Forest on Nokuse Plantation

The pitcher plant seepage, like the sandhill and the steephead ravine, are little gems among the tens of thousands of acres still to be restored. As longleaf, wiregrass, and fire are returned to the rest of Nokuse, plants and animals will spread from these hubs. Eventually, Nokuse Plantation will form a wildlife corridor with Eglin Air Force Base’s 464,000 acres.

Three hundred years is a major commitment, one to be fulfilled by people whose grandparents have yet to be born. A longleaf pine tree can reach four hundred years. An old growth forest will include several generations of pine, from these oldest to the youngest grass stage and bottlebrush pines. And the richness of the ground cover plants- what would it look like after a hundred or so prescribed burns?

It’s an image that can only exist in my imagination. Right now, we have juvenile gopher tortoises born on a restored sandhill, sandhills milkweed waiting for a sandhills habitat, and pitcher plants ready to expand from their hundred-acre savanna.

Botanizing Nokuse Plantation

1. Sandhill Plants

Here, we spent time looking for plants eaten by gopher tortoises. We also found a few pollinator plants.

Milkpea (Galactia genus)

We have a few different milkpea species in Florida. Milkpea’s are legumes, and as such are nitrogen fixers, a benefit for surrounding plants in this nutrient poor environment.

“It’s very important, especially to young gopher tortoises, because that leaf is so tender,” Walker says of milkpea.

Gopher apple (Licania michauxii)

We saw several of these small shrubs in the sandhill. In the fall,”it will produce a small whitish fruit the size of a grape.” Walker says. “And the gopher tortoises just absolutely love it.”

Wiregrass (Aristida beyrichiana)

During a fire, gopher tortoise burrows provide shelter for tortoises as well as hundreds of other species. Once the fire is over, the animals come out and- what is there to eat for the herbivores?

Luckily for them, plants respond quickly to a growing season burn. “When we burn this, the wiregrass starts coming up almost within the next couple days,” Walker says. “And the tortoises need food, so that wiregrass is important to the tortoises.”

Shiny blueberry (Vaccinium myrsinites)

Another food source for gopher tortoises, birds, and humans out for a stroll in the woods. We shot this in early June, when blueberries throughout our area are ripening.

Narrowleaf silkgrass (Pityopsis graminifolia)

Another important gopher tortoise food. Despite the common name, it’s not a grass. It’s an aster, blooming from July through October.

Soft greeneyes (Berlandia pumila)

We didn’t see a lot of showy wildflowers in bloom, but this member of the sunflower family provided a splash of color.

Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens)

Walking by the palmettos, we could hear buzzing. These large clusters of flowers attracted various pollinators, from honeybees to small butterflies.

Slimleaf pawpaw (Asimina angustifolia)

This is the larval host plant for the zebra swallowtail butterfly. Something had nibbled the leaves, but we didn’t see caterpillars.

Summer farewell (Dalea pinnata)

This is a plant with a tight seasonal schedule, one that signals the transition from summer to fall. Florida Native Plant Society’s Lilly Anderson-Messec taught me about this plant as we visited the Torreya State Park restoration in early September of last year. At that time it was blooming, and swarming with pollinators.

In early June, this plant is starting to establish itself.

Gopherweed (Baptisia lanceolata)

The Baptisia genus (indigos) is also in the pea family. Another nitrogen fixer.

Silver Croton (Croton argyranthemus)

This is a common sandhills plant, and a larval food for the goatweed leafwing butterfly.

3. Seepage Slope

Yellow pitcher plant (Sarracenia flava)

Goldencrest (Lophiola aurea)

Orange milkroot (Polygala lutea)