After a few weeks of isolation, we’re ready to go out and see something. Something big. Having produced a few segments on the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region lately, I’ve come to realize that it’s been a few years since we’ve had a family adventure there. Those outings had taken place in Torreya State Park. But now, I wanted the boys to see Alum Bluff, and steephead ravines. So I convinced Amy that we had to hike the Garden of Eden Trail.

The trail runs through The Nature Conservancy’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve (ABRP). Torreya and ABRP protect geologically and biologically unique steephead ravines, and the highest river bluffs in Florida. And both are restoring the native sandhills habitat in the uplands around the ravines. The Garden of Eden Trail lets you see all of that in a less-than-four-mile hike.

You may read elsewhere that the Garden of Eden is one of the more difficult trails in Florida. After all, we’re in a mostly flat state. You’re going to hike into and out of two branches of the same ravine on the way to Alum Bluff, and then again on the way back. Otherwise, the trail is fairly flat. Climbing down into a ravine isn’t too strenuous; it’s the climbing out where you’ll most exert yourself. TNC has installed steps to make the steep rise a little more manageable, and yet those might leave you winded anyway. (If you want to see how you’d get into and out of a steephead ravine without steps, check out this video from a couple of years back.)

Highlights of the Garden of Eden Trail

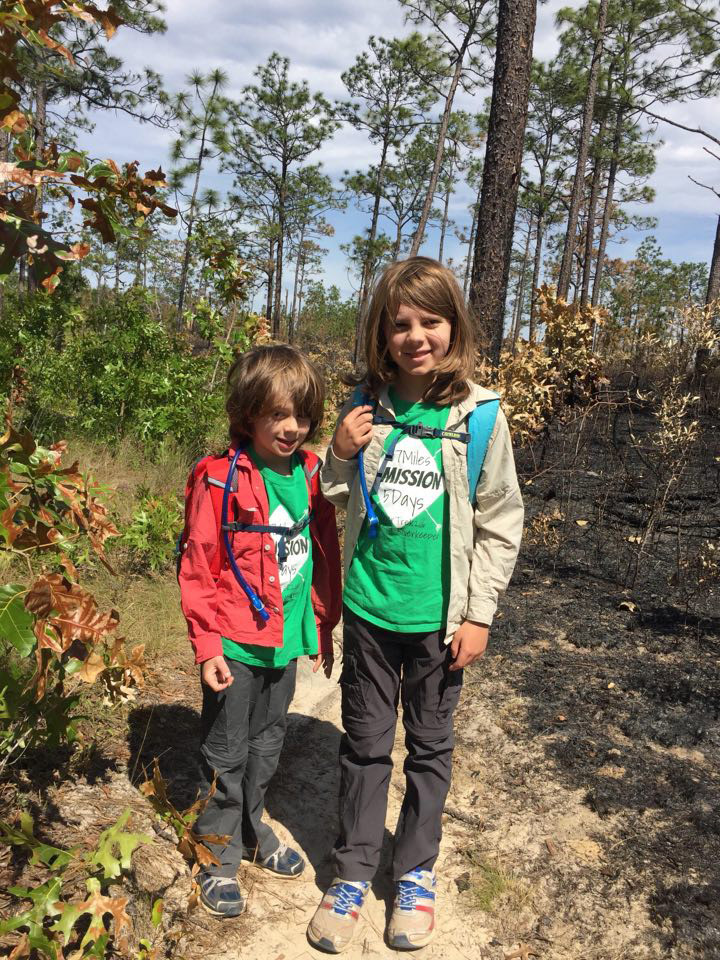

The elevation was part of the draw for us. During a trip to Colorado last summer, we found that the boys can get bored on flat trails, regardless of the scenery. They like to climb, and engage their arm and leg muscles. Their knees are much younger than mine.

For me, a big draw is the flora and fauna of the region. In a short period, you’ll hike through fire dependent sandhills, and wetter, shadier ravine slopes and streams. Each of these zones has its different plants, and the geological uniqueness of the ravines has attracted some interesting specimens. I’m going to have a field day on iNaturalist, as you’ll see in the photos below.

After a little more than a mile and a half, you reach the top of the highest river bluff in Florida. I consider it one of our state’s great vistas, from above and below. From the top, you see a panoramic view of the Florida’s largest river, in terms of flow. When you boat or kayak up on the Apalachicola, you can see the bluff a little more fully. It’s the largest geological outcropping in the state, and as we found on RiverTrek 2016, it’s full of fossils.

We’ll start with some trail basics. After that, we’ll share our experience on the trail, and show you what we saw. That includes the flora and fauna. What I’ll do is highlight a select few plants and animals in the following sections, and then below that, we’ll look at many more of the species we saw. We’ll also have an update on the trails at Torreya State Park.

Garden of Eden at a Glance

Length: Up to 3.75 miles, depending on whether you take the loop trail off of Alum, Bluff (we didn’t).

No dogs, camping, firearms, or hunting.

There are no facilities along the trail. Bring plenty of water and whatever snacks you need.

Social distancing note: In the wide openness of the sandhills, it’s easy to step aside and give someone a six foot berth. On the way into and out of the ravines, the trail is steep and narrow, and there might not be a safe place to step aside.

Visit the Nature Conservancy in Florida website for up to date information on the trail.

You can consult the map below for directions. A sign on State Road 12 directs you onto Garden of Eden Road, which leads to a small parking area.

We start in a charred landscape…

As luck would have it, The Nature Conservancy had a prescribed burn just three days before our hike. Right along the trail, from the parking lot to where it starts to dip into the ravine, was black and brown. But they only burned on one side of the trail; so, in a way, we’re getting the best of both worlds.

On one side, you have an ecological lesson of the type I subject my children to. “Look how empty everything is between the pine trees! Look at the dead oaks!” And then we see, just three days after the burn, that wiregrass is already starting to grow back:

You can see clips of the burn provided by The Nature Conservancy in the video above. Though TNC’s North Florida Program Manager David Printiss didn’t know we were coming, it sounds like he was talking to us:

“Today’s burn at the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines is being conducted right adjacent to the hiking trail.” He says, panning his camera as fire spreads. “Come back in just a few short days when all of this will be green and verdant once again.”

In another clip, which I didn’t use in the segment, he mentions that it’s the beginning of their burn season (they burned May 5). This is when lightning storms start passing through our area more frequently. It’s also the beginning of the growing season, and plants burned down to their roots will regrow more vigorously now. You can see how it continued to grow when I revisit a few months later.

And on the other side of the trail…

So, on the one side, we see the process that clears woody growth between the pines, and allows grasses and other ground cover plants to flourish. On the other side, we see those plants.

Right now, this gopher apple plant is starting to flower. It will eventually produce a fruit that is popular with small mammals and, as hinted at by the name, gopher tortoises. In fact, the plant wasn’t too far from a burrow:

Closer to the ravine, I see a small shrub with pink flowers. At first, I think this is Apalachicola rosemary, a plant that only grows here in Liberty County, at the edge of steephead ravines. But the leaves of this plant aren’t the needle-like ones rosemary has. It does smell minty, which Apalachicola rosemary is supposed to.

I enter it into iNaturalist as Apalachicola rosemary, as you should always venture some sort of guess. A false guess is better than no guess, as it’s more likely to be noticed by other users. One of those users suggested Florida calamint, which fits the description both in terms of how it looks as well as geographically, and in its habitat.

It’s an interesting flower in its own right. Florida calamint ranges from Walton County to Wakulla, and is listed as Threatened in the state of Florida. I’m glad to meet this plant.

These are just a couple of the plants we saw in this habitat. I don’t want to bog the story down with too many plants for those of you who are more interested in hiking than botany. For those who are into plants, scroll down for more pics and descriptions of what we saw in the sandhills.

Down into the Steephead Ravine

We enter the shade, and as the trail curves around the edge of a slope, the boys look down.

“Wow, we’re really far up!” Xavi says. It’s an impressive sight not hinted at by the surrounding landscape. You can see large hills or mountains from a distance. Walking up to the dense forest surrounding a steephead, though, nothing tells you that the land drops so precipitously.

Part of that is the relative narrowness of steepheads, which is shaped by the way in which they’re formed. It starts with the surrounding sandhill habitat. In this environment, water passes through the sand to whatever is below it. In the Munson Sandhills south of Tallahassee, the sand is directly over porous limestone. That is a land full of ephemeral wetlands and sinkholes, where water freely enters the aquifer.

The sandhills here sit over 150 feet above the Apalachicola River, along an ancient shoreline from when the sea level was much higher. The sand extends all the way down to about river-level, where it hits a hard rock/clay layer. Water percolates down to the rock, making aquifers just above the surface of the river. Sometimes the aquifers start to trickle out of the river bluff and into the river, and the trickles become streams that carve out narrow channels in the bluff. Over time, you get a steephead ravine.

The walls of the ravine can be as steep as 45 degrees, the angle of repose. Any steeper and sand would slide off of it. This makes the descent into the ravine quick and fun for children. At least it does if their dad doesn’t stop them to frame a few shots.

Pyramid Magnolia | Ice Age Refugee

On the way down the slope, we pass by a plant with a story to tell.

Many people come to the Garden of Eden and to Torreya State Park because it reminds them of hiking in the Appalachian Mountains. There is more than just a superficial resemblance to the ways in which trails climb and descend terrain. During the ice ages, plants and animals migrated south from the Appalachians as those mountains were covered in glaciers. When it warmed up again, many of those life forms felt enough at home in steepheads that they stayed.

The plant above is a pyramid magnolia. It’s either a variation of a Fraser magnolia (Magnolia fraseri var. pyramidata)- which is an Appalachian plant- or its own species (Magnolia pyramidata).

The pyramid magnolia and its cousins to the north were once a single species. After the ice ages, its population split, and each group evolved separately. Did the pyramid magnolia evolve enough to be considered a new species, or just a genetically distinct sub-species? That’s a question for another day. It is, like the Apalachicola dusky salamander and Florida Torreya tree, both an ice age refugee and a Florida native.

The Ravine Stream

The Garden of Eden Trail crosses the Kelley Branch ravine twice. If you look at the map above, you can see that there is a central ravine and stream, and a few smaller branches on either side. It looks almost like a misshapen Christmas tree. Our first crossing takes us over the largest lower branch of the tree.

The stream runs fast and clear over a sandy bottom. This is groundwater, seeping from the steephead theater, as Bruce Means calls it. So it’s nice and cool, around 68 degrees. The act of its seeping erodes the steephead theater and continues to move it further from the river, growing the ravine.

We’re seeing the insects below in the streams and the lower slopes. They’re a type of damselfly, which are closely related to dragonflies. These are hunters, picking flying insects such as mosquitos from the air. Not enough of the mosquitos, today, but that’s okay.

There were also a lot of panicgrasses growing along the trail, which I neglected to photograph. These are native plants that I let grow in my yard as weeds.

Hiking along the Slope

The steps out of the ravine are in rough shape, but safe. It wouldn’t be fun if the trail were too easy, would it?

Just past the steps, the trail is steep, and Amy needs to help Xavi keep his footing. Soon, we’re hiking along the rim of the ravine, and the trail flattens out. On one side of us, the land slopes out of view behind a tangle of vegetation. You never see the bottom from up here, though you can see that we are high up.

Right along this section of trail, though, we see flowers in bloom.

Carolina ruellia (Ruellia caroliniensis) on slope.

Redring milkweed (Asclepias variegata) on slope trail.

Smooth yellow false foxglove (Aureolaria flava) growing along slope forest.

Indian pink (Spigelia marilandica) on ravine slope.

Like I said, we’ll have more information on these and other plants below, for the enthusiasts.

After the trail turned and we started heading towards the second ravine crossing, Xavi noticed something on a log:

Fence lizards do a nice job of blending in with bark. We watch it for a second before continuing. The second ravine crossing is a little more involved than the first.

Back into the Ravine

Here we cross the main trunk of the steephead. The stream is wider, and the descent and ascent take a little longer.

They boys throw leaves in the ravine stream, watching how quickly the current caries them away. The water also carries the sand it erodes where it seeps out, depositing it into the Apalachicola.

Soon, we leave the shade of the ravines and slopes. But not after a good workout.

Back in the Sandhills

Now, the trails flattens out, and the trees are again more widely spaced. Interestingly, I smell burnt pine again, though they don’t seem to have burned in this section of the sandhills. Perhaps the smell moved over top of the ravine to here, not penetrating the thickness of trees around the ravine.

This section of the sandhills looks more open than those on the other side of the ravine. I wonder if, closer to the river, Hurricane Michael didn’t take out more trees here. David Printiss has mentioned, on an earlier shoot, that they’ve lost a fair amount of longleaf pine. Some of the dead trees are still standing; their barks will show it before their needles turn brown and fall.

Here, we see more plants typical of the sandhills ecosystem:

Another common sight in this habitat are these ant mounds:

I interviewed renowned ant researcher Walter Tschinkel about our native ant species, and this is one of the easiest for any lay person to identify. You’ll find the Florida harvester ant in dry sandhills. Those black bits of debris encircling their mounds are pieces of charred pine needles. No one understands why they decorate their nests, or why they occasionally redecorate them. But this is a recognizable resident of a fire dependent longleaf ecosystem.

Soon, we see the sign for the Alum Bluff overlook. We tried to get here early to get most of our hiking in while it was still cool, but I keep stopping to take photos of videos, both of the boys and their hiking but also of everything alive along the way. We feel the heat here where it’s less shady, and are looking forward to seeing the Apalachicola River.

Alum Bluff | The Highest Point Above Any Florida River

The view from Alum Bluff is one of the best in Florida, and we appreciate it all the more for the work it takes to get here. Could you imagine this place if it were at the side of a road, like some of the National Park overlooks out west? A little parking area, crowds of people waiting to get to edge so they could take their landscape shots and selfies. Waste baskets and restrooms, maybe a little scope you activate by depositing a quarter.

This is a view best appreciated a little sweaty. Here’s where you can take a break before heading back, and watch the river flow by. This water has 84 miles further to travel before reaching Apalachicola Bay. Along the way, it joins up with the Chipola River, and feeds and receives water from tupelo swamps.

You can see the outcropping in the distance behind the boys. Here’s a closer look.

Before we took this trip, I showed the boys some videos I’d produced in the area over the years. They were especially intrigued by the prospect of hunting for shark teeth on Alum Bluff. Four years ago, Assistant State Geologist Harley Means showed us a megalodon tooth he found here, a fossil from the largest shark to ever swim the earth. Twenty million years ago, there was a shallow ocean here, possibly enclosed by barrier islands, the dunes of which eventually became the sandhills we hiked through today.

Where is the Alum Bluff Sand Bar?

The first time I saw Alum Bluff, on RiverTrek 2012, I slept on a sand bar across the river from it. Panning the camera to that side of the river, the sandbar is not visible.

For ten months in 2012, the Army Corps of Engineers released the minimum flow allowed by law from the Woodruff Dam, 5,000 Cubic Feet per Second (CFS). In 2012, the Apalachicola River was the lowest it had been since people had started measuring it. An easy way to visualize the height of the river is in its sand bars, which are numerous north of the delta. Many of those have been made larger by the Corps, who dredged the river to deepen its channel, and dumped the dredge on existing sand bars.

Looking at the data from the Chattahoochee gauge on October 9, 2012, the Apalachicola River’s flow was somewhere between 5,000-6,000 CFS. The photo below shows how exposed the sand bar is when the flow is that low:

Looking the river gauge for today, May 8, the flow is about 25,000 CFS. The river now (on our hiking day) is carrying five times more water than when I camped on the sand bar. That night in 2012, by the camp fire, Retired US Geological Survey researcher Helen Roth told us of the importance of dry and wet periods on the river. When the river is higher, fish gain additional foraging ground, and insects to eat. I wonder if that boat in the first photo is finding fish taking advantage of this.

One more thing I’ll point out is that Florida has been in a drought for a couple of months, and yet the water is running high. The Apalachicola is fed by two Georgia rivers, the Flint and Chattahoochee. West Georgia has had much more rain than we have, and in late April, the Army Corps of engineers released a massive amount of water, bringing the river to flood stage on April 24.

It wouldn’t have been advisable to take a boat or kayak out that day, but I imagine it looked plenty cool from up here.

One last look before turning back

Once at Alum Bluff, you can turn back and return the way you came, or take a short loop trail along the bluff, which joins with the main trail in the sandhills. Either way, you have to cross back over the ravines again.

Here’s one last look at the river before we go:

As we walk away from the bluff, we see this cool little critter resting by the side of the trail:

I don’t shoot as much video on the way back, and we enjoy hiking at a better pace. It has done us good to get out and stretch our legs, and exert ourselves. The hike is a good mix of activity, geology not common in most of Florida, and a taste of why the Apalachicola River corridor is considered a biodiversity hotspot.

Update on Torreya State Park Trails

Last October, I visited nearby Torreya State Park to see how it had recovered in the year following Hurricane Michael. While the main section of the park is just a few miles away from The Garden of Eden, it was hit much harder by the storm. Its trail system was mostly impassible, and clearing trails on heavily vegetated slopes is slow work. And even when the trails are cleared, so many trees were killed or damaged that falling limbs are a real danger.

As of early October 2019, only 2.5 miles of the park’s 14 had been cleared. A few days ago, I contacted park manager Jason Vickery to see what progress had been made over the last few months.

“Right now we have around 10 miles of trail open. ” He told me. “Contract crews will be finishing up next week on the Torreya Challenge loop (which is still closed), and doing some weedeating and brush blading on the Torreya trail in the overgrown areas.

“We are super excited to say that all trails will be open in a couple weeks, but hikers should be aware that blazing may be sparse and signage may be missing due to Hurricane Michael.”

EDIT 5/28/20: Just after posting this, I saw this e-mail from Jason Vickery: UPDATE: ALL TRAILS ARE OPEN AT TORREYA STATE PARK!

Work on signage and blazing trails will continue through July, when an Americorps team will come in to help them finish. Americorps will also install new bridges where old ones had been damaged.

It’ll look much different than it once had, but the trails will still offer the same challenging terrain that make them and the Garden of Eden so popular with hikers.

Plants in the Sandhills | Part 1

Now, let’s take a look at more of the plants we saw on our hike! We’ll start on that first stretch of trail in the sandhills between the parking area and the first ravine crossing.

One plant that was just starting to flower was silver croton:

EDIT June 30, 2020- After an initial ID of Florida pineland spurge, a botanist recommended Greater Florida spurge based on the stem leaves pointing downwards. Comparing photos, I see that he was right. The ID also more closely matches the identification map for both species, as Florida pineland spurge has not been identified on the upper Apalachicola River. Where the pineland spurge has been ID’d throughout the state, the river is the western edge of the greater Florida spurge’s range, which has ben found throughout the panhandle and into Alabama.

Below is a greater Florida spurge about to flower. I look it up later, and see it’ll have a small, pretty flower in the not too distant future. It’s getting hotter and buggier, but if you can stand that kind of weather, it looks like a lot of flowers are getting ready to pop here soon.

The one below is a Gulf Sebastian-bush.

We were able to see a nice diversity of flowering plants in a short section of trail, and we’ll see more more sandhills flora on the other side of the ravine. Now, we head into the shade, and see a different assemblage of plants.

Plants in the Ravine Stream

A couple of the plants we see in the stream are the same as those the Leon County UF IFAS extension put in their wildlife pond. For every Appalachian refugee or rare or endangered plant species here, there are several more that will grow easily in your home space, and allow you to create native habitat.

Here’s one that didn’t make into the finished wildlife pond video, but that Rachel planted. I didn’t see it, or wasn’t able to identify it, when I went back later, and I tried to show a before and after of the plants she included.

We see a related sedge in the Carex genus in that video. This one is on the bank next to the ravine.

This one isn’t in the IFAS pond, but people do cultivate it. This is a summer blooming plant, just starting to flower.

I was hoping to see Florida star anise. It’s a spring blooming plant, and one that grows in ravine streams. Its flower has a foul odor; it’s a flowering plant of an old lineage. The first flowers predated bees and butterflies, and so they originally smelled like rotting flesh to attract flies as pollinators. I’m not sure, but I think the larger leaves in the lower right of this photo might be Florida star anise (no flower):

Plants Along the Slope Trail

Here is a milkweed species I had previously seen on the Overstreet trail at Maclay Gardens State Park. That’s another shady trail that runs along a ravine in parts. I checked the leaves for monarch caterpillars, but no luck.

Here’s another flower you’re likely to see in Tallahassee. I usually see it not too far from water.

I looked at the iNaturalist map for this, and it has also been identified on the Overstreet trail, and across the street in Elinor Klapp-Phipps Park, as well a handful of other shady spots in town. Looking west, the next spots on the map are along the upper Apalachicola River. A few were identified here, one in Torreya, and one in Chattahoochee. It has a higher density of IDs centered on Tennessee and its surrounding states.

This is a plant associated with the sandhills habitat; Yuccas thrive in dry, sandy soils.

A couple of weeks after our trip, I start seeing photos of this in bloom on Facebook. We scheduled our trip in part based on a cooler weather report, but if we had waited, we’d have seen more flowers.

My iNaturalist guess for this plant is clammy groundcherry. But, using the compare feature on the app, I see that a few members of this genus have similar flowers. EDIT 10/9/2022- an iNaturalist user has suggested Carpenter’s groundcherry (Calliphysalis carpenteri), a groundcherry species not in the Physalis genus. The user writes:

“I think it may be this species because of the clusters of 2-3 flowers/buds rather than single flowers and buds that you’d find in Physalis species.”

The flowers face downward; here’s a closer look:

Some members of this genus produce edible fruit, such as the tomatillo. A different goundcherry species volunteers in our yard, and, as a native fruit producing plant, I let it grow.

Critters Along the Slope Trail

Most of the wildlife we see on the trail are insects, but they’re at least cool looking insects.

Last month, I saw two different Hairstreak species in our yard. Here’s a third, and I have to tell you, they’re not easy to distinguish at a glance. If you can enjoy sitting with a field guide and picking out the differences in their wing patterns, butterfly watching might be for you. Here are the three different species. What differences do you see in their wings?

Striped hairstreak (Satyrium liparops) resting in the shade of a ravine slope.

White M Hairstreak (Parrhasius m-album) resting on lantana leaf.

Gray hairstreak (Strymon melinus) resting on pepper plant leaf.

Before entering the second ravine, we spot this katydid trying to remain inconspicuous amongst leaves:

This is a shieldback katydid, likely one of the eastern shieldbacks. The only shieldback identified in the area is a robust shieldback, but I’m not sure based on the photo.

Here’s one Amy spotted. In the last year-and-a-half or so that I’ve iNaturalized insects in the yard, or out and about, I’ve noticed that we have a lot of insects with no common names. There are just too many of them. It’s a testament to the diversity of life out there, and in an area as biodiverse as this, one can only imagine how many insects fuel the food web.

As the trail starts to dip into the second ravine crossing, we see this massive southern magnolia growing near the stream. At one point, the trail emerges from a tunnel of tight vegetation and we’re eye level with these flowers growing higher up on the tree.

Plants in the Sandhills | Part 2

Here are a few more of the plants we saw after emerging from the second ravine crossing:

This one hasn’t been confirmed on iNaturalist yet, but it seems a likely candidate. It’s only just starting to bloom, like so many plants we saw today.

Dogtongue buckwheat will flower in the summer. Even without the flowers, I like the red fringed leaves.

Sparkleberry is a Vaccinium, a genus that includes blueberries and cranberries. Its berries will feed everything from birds to small mammals, and even bears.

And finally, we saw a few more Florida calamint shrubs.

Thanks for tagging along with us today. This was a fun video to produce at a time when we’re being cautious about meeting up with people, such as the researchers, conservationists, and other outdoors people I enjoy interviewing. Research has been showing that it’s less likely to contract coronavirus outdoors, where I do most of my work. So I will be thinking about the best way to safely continue my work, even if it means having to get creative.