A couple of weeks ago, we visited the “snowy plover factory” at St. Joseph Peninsula State Park, and learned about the bird’s nesting habits. Today at Deer Lake State Park, two newly hatched chicks get banded.

Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog to receive more videos and articles about our local, natural areas, and subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Youtube Channel

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

“It’s good just to act like beach goers,” says Marvin Friel. “Just looking for shells.” We’re approaching a snowy plover nest at Deer Lake State Park, and we’re acting casual. The nest is up by the dunes, and we’re walking along the water. We look ahead at the waves, not wanting the parents to see us eyeing their chicks. Marvin takes a few sidelong glances before radioing Raya Pruner, “I think we’re going to approach now. Are you ready?”

The chicks are two days old, but they can already run. They can do this two hours or so after hatching. They’re quick, and they make Marvin work a little before he has both in hand. He has to move with speed but still be gentle as he scoops them up. His purpose today is to help, not to hurt.

Raya and Marvin, biologists with Florida Fish and Wildlife, are aware that this is a traumatic experience for the chicks and their parents. So they move as quickly and efficiently as they can, and with cameras pointed at them no less.

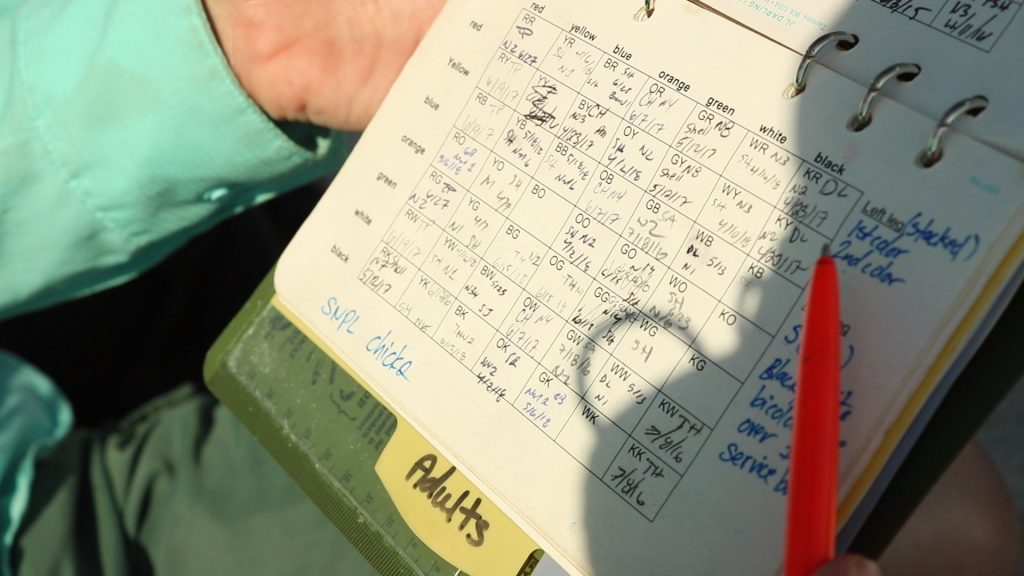

Raya is FWC’s Shorebird Program Coordinator for the Panhandle. She consults a book containing several pages of charts. Each sheet is a matrix of colors- seven by seven. These are the colors of the bands from which they’ll pick two to place on each chick’s left leg. Like the other birds on this page, the chicks will get a metal and a bicolored black and white band on their right legs. Each snowy plover tracked by FWC has a unique combination, which is kind of its name. The chart ensures that there are no repeats.

And now, please welcome black-orange and black-green to Florida’s shorebird banding program.

Raya Pruner holds a chart listing possible color combinations for banded snowy plovers in the Florida panhandle.

Why Band Shorebirds?

In our last post, we got to know the snowy plover. The dune habitat they prefer is mostly found on protected public lands, and so that’s where the plovers breed. But, outside of north Florida, a lot of the coastline in the snowy plover range has been developed, and so their numbers have declined.

To protect a species that’s being threatened by habitat loss, researchers have to understand what the animal does throughout its lifetime. In this case, we have a small bird that doesn’t stay put. The chicks can walk, but how far will they go for food? When they learn to fly after about 30 days, where will they go? And finally, where along the coast will they decide to breed?

A coordinated network of researchers and volunteers is working to find these answers. Regularly patrolling the protected coasts where this bird is most found, they spot and record band combinations, along with time, date, and location.

When black-orange and black-green are old enough to fly, they’ll strike out on their own and find a spot they like. Maybe they’ll try Tyndall Air Force Base, some twenty miles down the coast. They may find themselves further east at Cape San Blas, or head west to Perdido Key State Park. Like many local snowy plovers, they may head to southwest Florida.

Volunteers on any of those beaches will see a snowy plover and, from a respectful distance, note the band combination on their legs. They’ll enter the information into the appropriate database, where Raya and company can, over the years, keep track of this bird. They’ll end up knowing where it nests, how many chicks it successfully fledged, and how many nests it attempted during a breeding season.

What Have we Learned by Banding Snowy Plovers?

The chicks’ father was banded as an adult in 2013 at Camp Helen State Park, located just a few miles from Deer Lake State Park. Both are smaller state parks that serve to protect rare coastal dune lakes and their outfalls to the Gulf of Mexico.

“He’s at least six years old right now,” Raya says of the father. “And, of interest, he’s fledged six chicks since he was banded, which is what we were looking for. That’s at least one chick per year.”

That’s what they know about one bird. Having this information for hundreds of birds over several years has rewritten a few key facts about this species.

Snowy Plover chicks like to walk

We see how Marvin had to chase these two-day old chicks in the video. That’s one thing we can see with the naked eye- they can move. Unlike a lot of bird species, they have to go out and find food from the day they’re born. What was surprising is how far they go to forage.

“Because we’ve put bands on them, we’ve actually documented chicks of this age moving over thirteen miles.” Raya says. This underlines the importance of having space to roam. Deer Lake State Park has less than one mile of protected beach front bracketed by hotels and condos. And the beaches on either side of the park attract large crowds during breeding season.

But the park also contains the eastern edge of Deer Lake’s outfall. As Marvin explained in our last post, this is prime snowy plover foraging habitat. So while chicks are able to walk far in search of a meal, it’s critical that this area is healthy and well protected to keep the chicks safely within the park boundary.

This fact also helps explain why Saint Joseph State Peninsula is such a popular breeding spot for the species. With several miles of undeveloped dunes, snowy plovers not only have plenty of suitable nesting spots, but their chicks have space to roam and find food.

Snowy Plovers are Swingers

Another piece of information about snowy plovers would have been difficult to figure out without banding.

“We previously thought that these birds were monogamous,” Raya says, “but we found that they are polygamous, and nest with multiple individuals a season. ”

Snowy plover mothers leave their nests soon after their chicks hatch. Being able to identify them as individuals, spotters would subsequently see them make nests with new mates. An individual snowy plover might nest as many as three times per season.

It’s a breeding strategy that increases the rate at which they successfully pass on their genes.

Florida Audubon’s Bonnie Samuelson peers through a scope as Marianne Korosy looks on. Audubon regularly monitors shorebirds at the Nature Conservancy’s Phipps Preserve near Alligator Point.

What Do You Do if You Spot a Banded Shorebird?

While some individual birds had been banded previously, the banding program started in earnest in 2008. As we see, they’ve learned some interesting things in ten years, and perhaps there’s more to uncover. The exciting thing is, you can be a part of it.

Citizen science, done right, adds valuable knowledge without straining the financial resources of research entities. I’ll emphasize the done right part.

“It can be very complex, “says Bonnie Samuelson, Shorebird Program manager for Audubon Florida, “Which makes it a lot of fun.”

There are two important aspects of shorebird spotting. One is spotting the bird from a respectful distance.

Give Shorebirds Space

“You don’t want to disturb the bird when you get the bands,” Bonnie says.

For instance, if you spot a bird on its nest, you don’t want to get close enough to scare the bird away, leaving its eggs vulnerable.

Last Friday, Bonnie and I were on the Phipps Preserve on Alligator Point, looking to record footage of migratory birds. We learn a lot about their migration routes from banding, but we can easily disrupt a bird’s migration by getting too close to them.

Our north Florida coast is a “launch pad” for many migratory species. Some of these start in the arctic, and are here eating and building up energy to fly across the Gulf of Mexico, where they won’t have as many places to stop and take a break. If we scare them into flight, they use some of that precious energy.

This is where shorebird spotting isn’t necessarily for the casual beach goer. To be able to read the bands from a safe distance, you’ll need a good birding scope or binoculars. To snap a photograph where you’ll see and be able to read the bands, you need a little bit of a zoom lens.

This is a banded piping plover near Alligator Point. During the winter months, piping plovers migrate to Florida. In their winter plumage, the bird closely resembles the snowy plover.

Learn to Record and Report Banded Birds Properly

As citizen scientists, we want to make sure we’re collecting information properly, in a way that helps the researcher.

For one thing, it helps to know your bird species. Right now, piping plovers have migrated to our beaches from up north, and they closely resemble snowy plovers. Of course, the bands themselves would identify the bird, so if you recorded the combination correctly, Raya and her team might still identify the bird despite the confusion.

Then there’s the matter of correctly reading the bands.

“What we do is read the upper left leg, and the lower left leg,” Bonnie says. “And then the upper right, and lower right.”

Bonnie shows me a notation she’s made after seeing a snowy plover: S//W:X//BK SNPL

S stands for service, the metal bands used by the US Geological Survey, which maintains a database of banded birds. So that’s service over white on the left leg, no tag on the upper right (X) over black. SNPL is the shorthand for snowy plover.

Once you have the information, you need to report it to researchers. Both bandedbirds.org and FWC’s Shorebird database require you to create a login, and you’ll want to familiarize yourself with the websites. There’s a little bit of a learning curve here.

If you’re not a seasoned birder and you’re interested in spotting banded shorebirds, I would recommend connecting with the Florida Shorebird Alliance. There are plenty of volunteer opportunities where you can help shorebirds and receive knowledge from experienced birders.

Other Banded Birds

We’ve done a few stories on bird banding over the years, with Jim Cox of Tall Timbers Research Station. These were all birds of the longleaf pine ecosystem, who have suffered from habitat loss just as the snowy plover has. Two are endemic to the longleaf forest, and the third is a winter migrant.

The Red Cockaded Woodpecker

There are three bird species found in the longleaf habitat and nowhere else: the red cockaded woodpecker, brownheaded nuthatch, and the Bachman’s sparrow.

The American southeast used to be covered with 90,000,000 acres of this ecosystem; today, there is only 3,000,000. Of interest to the red cockaded woodpecker is that only 10,000 acres have never been cut.

RCWs need mature longleaf pine to make a nest cavity, 90 years or older. And the majority of the trees in our forests just aren’t that old yet. Until more of today’s forests mature, this woodpecker relies on artificial cavities inserted into younger trees.

When we were filming our Roaming the Red Hills series, Jim captured a newly hatched woodpecker to band on camera.

Bachman’s Sparrow

While the red cockaded woodpecker needs mature trees, the Bachman’s sparrow relies on an open understory. A properly maintained longleaf forest burns every two to three years, which creates the grassy habitat this sparrow needs to thrive.

This bird has suffered from habitat loss, and is also affected by forest land that isn’t burned regularly.

When the Tallahassee Scigirls visited Tall Timbers a few years ago, Jim captured the sparrow above using a mist net.

Henslow’s Sparrow

Unlike the two previous birds, the Henslow’s sparrow visits our longleaf forests in the winter. During the rest of the year, it makes use of open grassland up north. So, like the Bachman’s sparrow, it’s at home in an open understory.

Jim caught this sparrow with a mist net and banded it for our EcoShakespeare project a few years back. We were in an old growth longleaf forest near Thomasville, and had just watched a scene from a Midsummer Night’s Dream. Jim joked that when researchers looked up the bird after spotting it, they’d see that it was a part of a Shakespearean production.

Tracking the Monarch Migration through Tagging

You can’t band a butterfly’s legs, but you can tag its wings with a small sticker. This is how, decades ago, scientists uncovered the secrets of monarch migration. As this butterfly is threatened by habitat loss, and climate change alters its migratory patterns, tagging can continue to give us important information about this species.

Here, we visited the St. Marks Refuge to tag monarchs as they prepared to fly to their wintering grounds in Mexico. While the Refuge was established for migratory birds, it has been invaluable to monarch butterflies as well.