Just over a year after it dried down, I visit Lake Jackson and find it holding water- for now. Dr. Tom Sawicki is netting the lake edge, or what has recently become the lake edge again. After a year of low water levels, the lake has expanded beyond scattered pools, and Porter Sink is submerged. Water is starting to reach the vegetation surrounding the lake, the habitat of Crangonyx apalachee. But Tom isn’t finding the small amphipod today.

Tom Sawicki is the principal investigator of Florida A&M University’s Groundwater Biodiversity Lab. He and his students have been diving into caves across Florida looking for minuscule, shrimp-like crustaceans. Doing this, they’ve discovered a few new species living in extreme environments. Crangonyx apalachee is a surface water relative of those blind cave dwellers. And Tom’s lab discovered it almost by accident.

What brought Tom to Lake Jackson was its groundwater connection with Wakulla Spring. A dye trace conducted by McGlynn Labs has connected Porter Sink to the spring; when water drains into the sink, it travels underground to Wakulla. Tom was out on a boat collecting water samples from the lake with the Wakulla Springs Alliance, and his graduate student at the time, Andrew Cannizzaro, decided to stay back and net the area by the boat ramp.

That impromptu act of netting paid off. Taking his samples back to the lab, he and Tom found that they had a species new to science.

They’ve found closely related Crangonyx in nearby lakes, but so far, C. apalachee is found nowhere but Lake Jackson. So while Tom and his current graduate student may not see the little critter today, in June of 2022, this isn’t its first rodeo. It should know what to do when the lake dries down. Tom just has to figure out what that is.

From the Lake Jackson Food Web to Mars

Tom Sawicki’s interest in amphipods and isopods may have more to do with outer space than lake ecology. His lab studies creatures that live in the cave systems beneath springs and sinkholes. These are dark places with few food sources. When he thinks of what it takes to survive in such an environment, his mind goes to Mars. In fact, the first thing you read when you visit his lab’s website is this:

Studying life in extreme environments can provide insights into how life may survive on planets such as Mars. For instance, it is possible that deep below the Martian surface groundwater flows through the rock’s interstices. Within those spaces, even today, life may thrive.

Groundwater Biodiversity Lab website

A few years ago, I went to Merritt’s Mill Pond in Marianna to talk to Tom about a new species his lab had found in the springs there. As he dove into Hole in the Wall Spring, Andrew netted the area outside the cave. He quickly found a couple dozen small crustaceans- amphipods and isopods.

Amphipods resemble shrimp, but they have no carapace. They swim in the water while isopods crawl on the bottom, and there are terrestrial isopods as well. The roly-polies in your garden are isopods. The amphipods and isopods Tom studies are a few millimeters long- small, but numerous.

At some point in the distant past, some ancestors of those animals swimming in Merritt’s Mill Pond drifted down into the cave. Over eons, the critters trapped in the cave adapted to its extreme conditions, and evolved into new species.

In that segment, we focused on the cave critters. But what Andrew told me on the boat stuck with me. Small amphipods and isopods are found in every lake and pond in Florida, and in large numbers. He estimated that in Lake Jackson alone, they would number in the millions.

The Bottom of the Food Web

If there are millions of any type of animal in a body of water, you can imagine they have some importance to that ecosystem. But when it comes to the various species of amphipods and isopods in the lake, Tom says they don’t quite know what that might specifically be.

They know even less about the role of any individual species. What niche might Crangonyx apalachee fill compared to other Crangonyx species, or the more common Hyalella species of amphipod?

“We do know, however, that biomass in these lakes is relatively high,” Tom says, “and so they are important in terms of a food source for small fish, for larger crustaceans, but particularly fish. And so they’re going to be really, really important in terms of, you know, small fish eat the amphipods, large fish eat the small fish.”

Walking around the edge of the lake, frogs hop into denser grass for better cover. Wading birds from great blue herons to wood storks forage at the edges of lakes and ponds. Even if those animals don’t eat Crangonyx apalachee directly, they may eat something that eats it, or that eats the things that eat it.

Tom admits that they have been focused on identifying species rather than studying their behavior. We’ll talk more about that below. But identification is a first step to understanding.

Adapting to a Lake Where Water Disappears

One thing Tom knows about his lab’s new discovery is that they found it in the grass at the very edge of the lake. This, he says, is the lake’s upper littoral zone. On our coasts, the upper littoral is also known as the intertidal zone. Intertidal ecosystems are submerged at high tide, and exposed at low tide. Salt marshes and oyster reefs are adapted to these daily cycles, as are the host of marine animals that inhabit them.

We don’t typically think of water levels in lakes as being so dynamic. But the edge of a lake isn’t as set as the blue line we see on a map. Even between dry down events, Lake Jackson will contract and expand based on rainfall and evaporation during dry periods. Crangonyx apalachee‘s littoral zone is possibly the most dynamic of the lake’s habitats. And that’s without the sinkhole becoming exposed.

When we looked at the history of dry downs in Lake Jackson last year, we saw that it’s not uncommon for the sinkhole to go dry multiple times over an extended period.

When we visit with Tom in June, Lake Jackson holds water, and does for a couple of weeks more. It’s still low, though- I couldn’t see a boat launching from Sunset Landing, and Faulk Drive Landing has been closed to motor vehicles for some time. By the start of July, it dries down again. I visit on the morning of July 11 to film the sinkhole. Then, a storm that night fills the sinkhole basin, but water has not reached the upper littoral zone.

By the time I publish this post, a tropical disturbance in the Gulf of Mexico could fill it further.

An animal of the upper littoral zone of a lake is adapted to dry conditions now and then. And an animal adapted to Lake Jackson even more so. The question is, how?

Where Do Amphipods Go When Lake Jackson Dries Down?

Tom and his current graduate student, Joshua Sisco, aren’t finding any amphipods here in June of 2022. No Crangonyx apalachee, nor any of the much more common Hyalella species. Wherever these amphipods went during the dry down, they’re not quite ready to return.

There are plenty of insect larvae in the muck- small beetles, dragonfly and damselfly larvae, something that looks like a pre-adult mantis. Tadpoles and small fish are swimming around our muck boots. But no crustaceans. We end up driving to Piney Z. Lake, where they quickly net dozens of Hyalella by a couple of the fishing fingers. Typically, amphipods are numerous by the edge of a lake.

I ask Tom about where these critters might have gone. Here are a few possibilities:

1. They retreated into smaller pools of water- and are staying there

If you try to envision a dry down without ever having seen it in person, you might imagine an entirely empty lake basin. Thankfully for the fish in the lake, that isn’t the case.

As we saw when we visited last year, there are pools of varying sizes in the lake bed. There’s also a good sized part of the lake that stays submerged, sending a continuous stream into the Porter Sink Basin when it’s exposed. The humans with fishing poles and nets, as well as the crowds of wading birds, tell us that plenty of life concentrates itself in the remaining water.

The amphipods at the edge of the lake may have moved to one of these spots to stay submerged. If so, they may stay there for a while, even as the lake holds more water. As we’ve seen over the past year, the lake may temporarily hold water several times before the dry down event is truly over.

It can take time for water to fill the space beneath the lake. So an animal that flees into a deeper area might stay there until the lake holds water consistently for an extended period of time, so that it can reduce the risk of being stranded if the water unexpectedly retreats.

2. They retreated into the sediment below the littoral zone

After twenty or thirty minutes of fruitless netting, Tom sends Joshua to get the Balrouge pump out of his truck.

“It’s commonly used for the Hyporheic zones of streams and rivers,” Tom says. “The Hyporheic zone is a sort of a region below the benthic layer.” Benthos, the benthic layer, is the surface of rocks and sediment at the bottom of a water body. Beneath a river’s benthic layer is the Hyporheic zone, where water flows beneath the surface of the riverbed, bleeding into groundwater. The Hyporheic zone is a refuge for microbes and macroinvertebrates; macroinvertebrates are minuscule animals that are just visible with the naked eye, such as amphipods.

As we learned last year, water is always flowing down through Lake Jackson’s sandy bottom, and into the aquifer. Might the saturated sediments beneath the lake be filled with the same kinds of critters found beneath a riverbed?

Tom pumps a few times, expelling an attractive brown sludge into his net. Rinsing it in the water, sediments wash off of clumps of well preserved algae. This is what Crangonyx eat, but the fact that it’s so well preserved beneath the surface makes Tom skeptical about finding amphipods there.

“The question is just how would they survive anoxic conditions down there,” Tom says. “Because clearly not a lot of oxygen, not a lot of decomposition going on.”

Algae hasn’t decomposed because there’s no oxygen beneath the bottom, so how would an amphipod survive? Tom doesn’t find anything alive in the algae.

3. There aren’t adult Crangonyx apalachee in the lake right now.

A few months back, we took a look at efforts to bolster the population of frosted flatwoods salamanders in the Apalachicola National Forest. This is an animal adapted to another water body with a more seasonal wet/ dry cycle. The ephemeral wetlands near Sumatra have historically dried over the winter.

One of the salamander’s food sources is amphipods. Before the wetlands dry down, the small crustaceans lay eggs, which survive in the sediment until the wetlands refill. I asked Tom if Crangonyx apalachee might do something similar.

“We collected these things in October,” says Tom, “so there may be a seasonal aspect to their emergence, which would potentially explain why we’re not seeing anything here in June.”

But how would that play out in a place with a wet/ dry cycle not tied to seasons? And with the potential for repeated dry downs over the course of months or years?

With Changing Water Levels, Changing Vegetation

As Tom and Josh net the lake edge, it occurs to Tom that all of the plants around us have started growing here in just the last year. Andrew found Crangonyx apalachee much closer to the boat ramp, and the plant species are a little different here than they were back there. Different place, different plants.

I took similar photos to the one above last June, and right around the same area. Aquatic plants are stranded on land, and terrestrial plants start to grow. But how will those terrestrial plants fare when that piece of bottom is once again submerged?

It makes me wish I had visited the lake regularly over the past year, to document the changes in plant communities in and around it. That spot above would have been dry in June of 2021, and yet we see growth that is new in July of 2022. How many times did plants grow and die here, either drowned or dried out?

Right around where Tom is netting in June is pickerelweed, which grows in shallow water. Behind that is swamp smartweed, which grows in moist soil, and can be semi-aquatic. These plants grew and flowered within the last year. Bees are happily feeding as they net. Within another year, these plants may be gone, and where we’re standing could be a few feet underwater.

A New Piece of the Lake Jackson Puzzle- and More Questions

Over tens of thousands of years, every plant and animal in Lake Jackson adapted to the lake’s changing water levels in its own way. At the same time, they formed relationships with each other. Crangonyx apalachee was found in an area where it was sheltered by grassy plants at the edge of the lake. It eats algae, and is eaten by animals larger than it.

A dry down’s effect on one of these organisms affects every organism with which it has a relationship, and vice versa. Likewise, learning about one organism’s adaptation to this environment can give us clues about that of another.

This is what’s exciting about a new species discovery. Now, we have another piece of the Lake Jackson puzzle. And yet, with this newly described species come more questions. Here’s a lake, not deep in the forest, but just outside of Tallahassee, and we still have much to learn about it.

One thing Crangonyx apalachee can teach us lies in its DNA.

DNA and mapping the formation of waterways in Florida

When it comes to identifying creatures of this size, with several similar looking species, Tom says that advancements in DNA testing have been a “game-changer.” Instead of spending considerable funds to send samples off to be tested, Tom can sequence DNA right in his own lab.

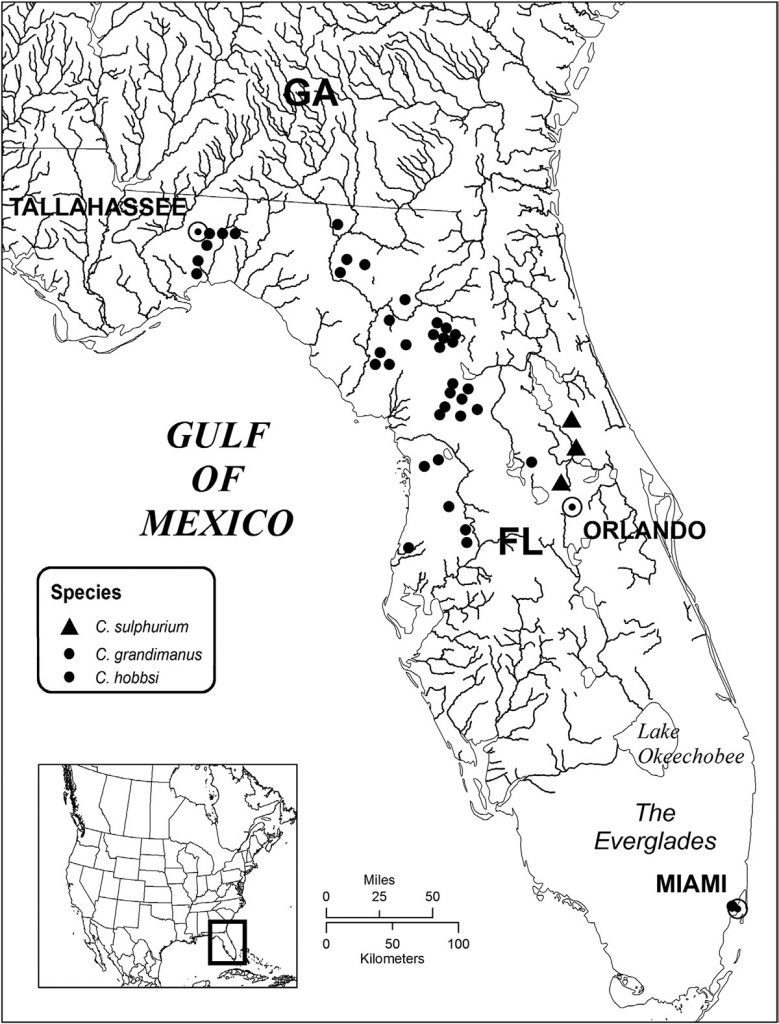

To Tom, the DNA tells a story of how land and waterways change over millions of years. Many Crangonyx species in Florida are closely related, meaning that- in geologic time anyway- they had common ancestors in the not too distant past.

“It’s sort of a simple thing for folks to understand,” Tom says, “you know, you would expect your DNA to be more similar to your siblings… than, say, to your first cousin, and then more similar to your first cousin [than to] your second cousin. Species are going to be the exact same way. As long as you’re exchanging genes, you’re going to have similarity in your DNA.”

If a Crangonyx species has less DNA in common with species A than species B, it stopped exchanging genes with species A further in the past. What would cause that stoppage for small and numerous amphipods is a physical separation. Waterways that were once connected, became disconnected.

Florida Rises from the Ocean

Florida has spent tens of millions of years trying to get out from under the ocean. We’ve succeeded at it for the last couple millions years, but history shows it won’t last. Oceans have risen and retreated, constantly (in geologic time) reshaping our state.

When Tom looks at the DNA of Crangonyx species in Florida, he’s thinking about saltwater rising up and separating freshwater bodies. This in turn would have separated freshwater crustaceans of a single species long enough for them to evolve into two or more species. Tom’s wondering whether this accounts for more endemic, hyper-local species here than up north, which has stayed consistently above water.

“Freshwater invaded in this region relatively recently in terms of geologic time,” Tom says. “The question is, as we move north, will we see the same level of endemism? When I say endemism, I mean, you know, species are found in this really small, strict location and don’t seem to be found elsewhere.”

Even before they become new species, different populations within a species can become distinct enough to show a separation. In our story from a couple of years ago, we saw how Tom used DNA to define populations of cave Crangonyx species. A couple of different species range between Tallahassee and Tampa. This means that, at some point, the aquifer was connected enough for these small critters to have spread across that distance.

Somewhere around Lake City, however, there was a split. Groups on either side were more closely related to each other, and Tom even identified some sub-groups. Parts of the aquifer that had been connected, became disconnected.

More New Species on the Horizon

Dr. Tom Sawicki is working on describing a few more new species, as is Joshua Sisco. It’s nothing they can talk about now. But with each newly described species, Tom gets a clearer picture about the evolution of amphipods and isopods in Florida, and about the waterways they inhabit.

That comes, of course, with more questions. About their histories, yes, but about their lives as well. They may not all be as mysterious as Crangonyx apalachee. But, just as learning about Crangonyx species in the Floridan aquifer can teach us about the connectivity of water underground, maybe Crangonyx apalachee will end up teaching us something about the ecology of Lake Jackson.