The interview over, we turn our attention to Bruce Means’ office. We have returned from the tepuis of South America’s Guyana Shield, conjured from decades of memories. We are, once again, surrounded by shelves of ecology books, binders of collected research, scattered fossils… and also, live snakes.

“It is named after me.” Means says, cradling a brown and white kingsnake. “It’s a species unique to the Florida panhandle… His scientific name is Lampropeltis meansi.”

The Apalachicola kingsnake is either a closely related species, or subspecies (Lampropeltis getula meansi) of the eastern kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula). Its range is small, confined to the Apalachicola Lowlands region of Liberty and Franklin counties.

Means first found one of these snakes after arriving in north Florida in the 1960s. Sure that this was a distinct species from the eastern kingsnake, he conducted years of breeding experiments. Finally, a colleague of his did the DNA work, and honored Means by naming it after him.

As we’ve learned on our previous adventures with Bruce Means, he’s found several species new to science by doing the dirty work. The literal dirty, wet, mucky work, in often uncomfortable conditions. This is true of his work here in the panhandle, and it’s also true of his work in South America.

That work abroad has recently landed Means a National Geographic cover story and documentary.

Tepuis of the Guyana Shield

Looking for salamanders in a steephead ravine in Torreya State Park takes some climbing and maneuvering. It isn’t easy, but most any able bodied person could manage it.

A tepui, on the other hand, is a bit more of a challenge.

“Tepuis are very simply mesas,” says Means, “and a mesa is a flat topped mountain… on the summits, they are lost worlds, let’s say, that are surrounded by vertical cliffs on all sides, so that one can’t easily climb up a tepui.”

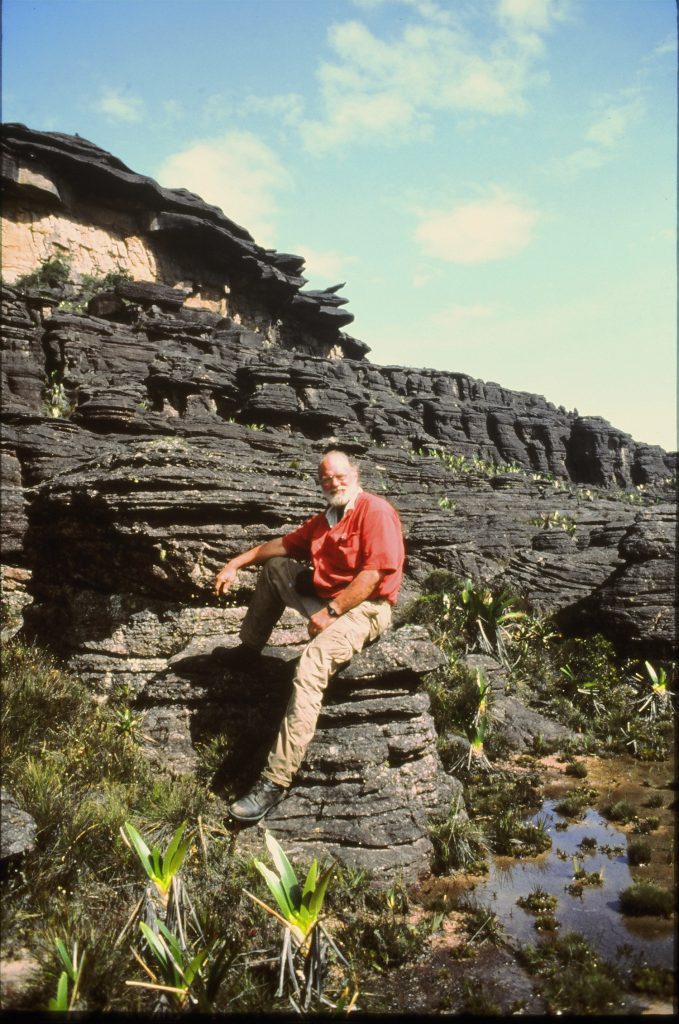

There are over 100 tepuis in the Guyana Highlands area of the Guyana Shield. This 1.7 billion year old geologic formation covers the northeast corner of South America. Over time, as the land here has risen, rain water has worn away much of it, leaving behind what Bruce Means calls “Islands in the Sky.” The tepuis rose thousands of feet above the surrounding rainforest, and plants and animals on them became isolated.

It’s a biologist’s dream. Means started visiting the Guyana Highlands in 1985, and was soon self-funding return expeditions.

“I eventually became familiar enough with the biology of the area that I could write grant proposals. And then I got involved with National Geographic, which funded some of my expeditions and did some documentaries, culminating in the last one, which I just completed.”

Climbing Weiassipu, for Science and Adventure

This last expedition exemplifies the appeal of the place to a biologist.

First, it’s a grand adventure. He conceived of the trip with fellow National Geographic Explorer Mark Synnott, a professional climber. Synnott brought in Alex Honnold, the famed star of the documentary Free Solo. Honnold and Federico “Fuco” Pisani would climb a tepui called Weiassipu, and look for frogs on the cliff face.

Over the years, Means and a handful of other biologists had been helicoptered to the tops of tepuis to study their flora and fauna. But the cliff faces had species never before studied by scientists.

Never before studied by scientists. For Bruce Means, this is the real appeal. Evolving in isolation for so long, many plants and animals on tepuis are endemic to the region, or even a handful of mountaintops. And because of the effort needed to explore them, there are untold species never before seen by human eyes. If a researcher can find a way to get up there, they can be the one to find them.

In this regard, the expedition was a success. But it came at a cost.

The Physical Demands of Field Research on Tepuis

“If you read the magazine article and see the documentary,” Means says, “you find out that I petered out physically. And yet, I had teammates with me, the mountain climbers, that actually made sure the expedition was a success scientifically.”

Means turned 80 on an expedition that would have been physically challenging for anyone. Even the approach to the tepui involved a multi-day hike through virgin rainforest. “The trails that we create are very difficult… they’re usually wet and mushy because we’re in either rainforest or cloud forest conditions.”

With no nutrients in the soil, Means says, the trees’ roots evolved to grow aboveground. “So you’re walking along and you’re stepping on these roots and you’re slipping and you’re getting your foot caught. And so it’s challenging. And for an 80 year old man, I had some serious falls.”

Their team included about 70 local Akawaio people, who guided them through the landscape.

“We got to rivers and streams and creeks and the Amerindians had felled trees across them so they could balance and teeter across, as did everybody else,” Means recalls. “But I couldn’t do that. My sense of balance is shot. So I had to clamber down into the creek itself and either swim or crawl or drag myself through the water. Get up the other side. Straight banks- mucky, spidery.”

The plan was for Honnold and Pisani to climb Weiassippu, and find a way to lift Means to the top. I won’t rehash the article. You’ll have to read it to see if Means made it. Mark Synnott does a wonderful job describing the struggles and successes on their journey.

The successes, by the way, include several species new to science.

Naming Species New to Science

“It’s a thrill for a field biologist beyond any measure to be the first one to find and recognize you’ve got a species new to science, and then do the work of naming it.”

The work of naming it. For any of us who do work in the field, the field is what people most associate with our jobs. The fun part. But whether we’re shooting video to edit later, or collecting specimens to analyze later, often, we spend most of our time at a desk.

Let’s look at the work that goes into identifying a new species. First, you physically travel to its habitat. In this case, tepuis and the rainforest surrounding them. Bruce Means has spent decades learning the animals in these locations, and so he knows when he sees one that doesn’t quite match a known species.

Bruce Means couldn’t share photos of the species new to science found on his last expedition, as he’s still writing those research papers. Instead, he sent photos of these related species from the Guyana Shield. He also found one new lizard and one new snake species. All images courtesy Bruce Means.

So he takes photos, and returns to Tallahassee with samples. It’s one thing for an animal to look different from known frogs, lizards, and snakes, but it’s another to define one as a distinct species. There are characteristics that need to be identified, and laid out for others to learn from.

This is the work Bruce is doing now, and he estimates it will take years to finish. Now, after the adventure is over, “when you sit in the office and dream of the fun you had out in the wild. And you have to grind through all the details of writing up a scientific research paper, which is a culmination of all that work.”

Bruce Means’ Legacy

Bruce Means mentioned his age more than once during our interview, and that he’s likely made his last expedition to the Guyana Shield. I say likely because he refuses to rule it out.

He’s in a reflexive mood. This one chapter of his life has closed, maybe, and his mind is on his legacy.

Closer to home, that legacy includes serving as director of Tall Timbers Research Station, and founding the Coastal Plains Institute. There are parks and other conservation lands we enjoy after he surveyed them and found habitat worth protecting. And, of course, there are the species he did the work to describe, from the Apalachicola kingsnake to the Apalachicola dusky salamander and Hillis’s dwarf salamander, to name a few.

That legacy now includes a National Geographic documentary that not only features his work, but features him as a protagonist. His career is charmed in that he’s been able to spend so much time working in not one, but two remarkable bioregions. The Guyana Shield is biodiverse and full of endemic species; but then, so is the Florida panhandle.

“Florida, from about the Suwannee River to the Perdido River, is one of the top biodiversity hotspots of the United States and Canada,” he says. “I have been fortunate in my career. I got my degrees at Florida State University, [and] in the process of studying the biodiversity of the panhandle of Florida, I’ve done research on snakes and frogs and lizards and the like, but also on ecosystems and fire ecology and all the things that go together to make this panhandle such a fabulous place.”

How to Watch and Read

The story of Bruce Means’ last tepui expedition is in the April issue of National Geographic. The documentary lands on Disney Plus on April 22, 2022- Earth Day. Means will give a talk on his tepui research as part of the Tallahassee Scientific Society’s Horizon Lecture series. This takes place Wednesday, April 27 at 7 pm, at the Challenger Learning Center.