It’s a little after 6:00 am, and all I can see in my headlights is tall grass. In that tall grass is the car I’m following; off to the sides is darkness, water. My car struggles to stay straight on the overgrown levies of the Saint Marks Refuge, and my hands stay busy on the wheel. Soon, Don Morrow and I are standing in the dark hearing least bitterns and frogs, and a distant barred owl. We’re in position to count shorebirds.

Don does this roughly twice a month, based on the tides. “I’m looking for a 2.5 foot tide, at least, at the mouth of the St. Marks River,” He explains. High tide today, September 11, 2020, is at about 7:50 am. The high water on the coast will drive shorebirds to the Refuge’s interior ponds, where they’re easier to count. It’s a few weeks into winter migration, and Don is seeing more and more birds with every survey.

But the value of his data isn’t strictly in the season to season numbers, it’s in the year to year. A study published last year found that North America has about three billion fewer birds than in 1970, and that shorebirds have declined by about a third. While the Refuge offers prime coastal habitat, many of its winter migrants breed in the ever warming Arctic. Habitat loss elsewhere could affect numbers here.

Don’s data is useful to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which has had volunteers survey shorebirds for several years. He also likes to play with the numbers himself. “I play with it and graph it, and I look for patterns, and I see what’s going on. And it helps me to understand what’s happening on the Gulf.”

6:30 am: Stoney Bayou II

We listen for the last sounds of the night hunting birds. “Chuck-will’s-widows have stopped calling,” Don says. The summer nighthawks have moved on, but others are migrating in. He points at a cypress dome I can’t see, which is where he would expect to hear barred owls call from.

Being here now may or may not help his data, but we start our day with a fuller feel for life on the Saint Marks Refuge. “I like watching the seasons unfold,” Don says. “I like being part of the morning as the night ends and the day begins.”

Don Morrow had been birding here for decades before taking on the shorebird surveys.

“I’ve been a birder since I was a kid. And I’ve been a birder at St. Marks since before I moved here. Been here thirty-five years. I’ve led field trips at St. Marks for maybe fifteen years. And I retired a couple of years go, and I asked them, ‘What do you need? I’ve got time.’ And then they said, ‘Would you [like to do] shorebird surveys?'”

Citizen science works best when it’s a win/ win for the scientist as well as the organization. US Fish and Wildlife gets their data, and Don gets to immerse himself in one of our area’s premiere birding destinations. Sometimes he gets torn up by mosquitos. One time, he watched a bobcat kitten playfully pouncing its mother’s tail for fifteen minutes. He sees, hears, and feels a different side of the Refuge than most of us get to experience.

The Pools and Ponds of the Saint Marks Refuge | Good for Ducks, Good for Shorebirds

The sun rises on Stony Bayou Pool II, not that we can see it. It’s a blue, misty morning. The pool is a little too flooded for shorebirds, which like sand or mud flats, and shallow water. Don focuses on the mud at the edges of the pool, where he starts spotting blue-winged teal, the first of the migratory ducks to arrive at the Refuge. They aren’t here to stay.

Blue-winged teal use the north Florida coast as a rest stop between the arctic and the northwest corner of South America. “They’re always the last to finish passing through, and the first to get back.”

We see more shorebirds on Stony Bayou I, and more of the teal as well. Again, the water is too deep for shorebirds in most places.

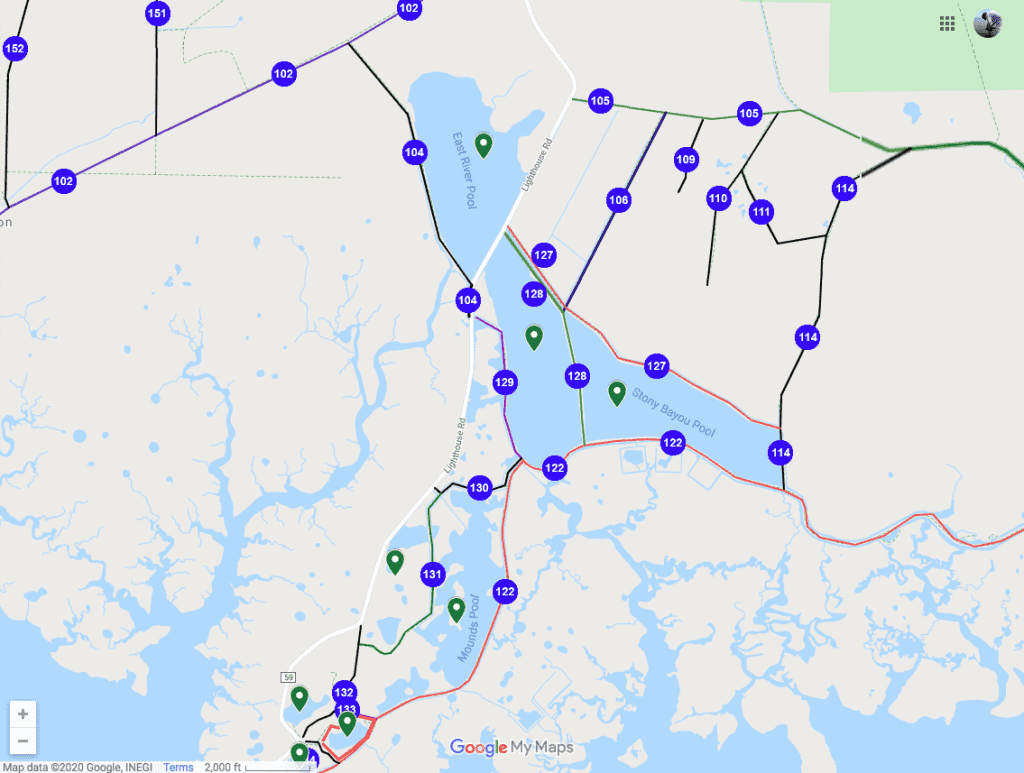

“In order to keep woody vegetation from establishing in the ponds,” Don explains, “they have to be flooded at least part of the year.” The Refuge manages the levels of its interior ponds, closing gates at high tide to keep water in when they need it. The pools are man made, impounded by the Civilian Conservation Corps when the Refuge was established in 1931. Their goal was to “provide a resting place for wintering ducks.”

The pools also ended up being good habitat for the 31 species of shorebird that stay at the Refuge throughout the year. “When you protect that land for ducks, it’s being used by other birds, it’s being used by bobcats, it’s being used by any number of different creatures.”

Tower Pond

We finish circling the Stony Bayou pools, passing Mounds Pool to get to Tower Pond. The water level here is much lower than in the other pools, and you can see shorebirds of various heights walking all over the pond, and longer legged wading birds as well. There are many more species here, and in much greater numbers than we’ve seen so far.

Don focuses on one species at a time, starting with marbled godwits, the largest shorebird here. I shoot video of all the action in the pond, and every once in a while Don calls out a species count. Eighteen willets, migrants from the Great Basin in the western US; the willets that bred here over the summer have already left for South America. Fifty eight semipalmated plovers. Twelve black-bellied plovers, some still in breeding plumage. Thirty four short-billed dowitchers.

We see a number of dark grey wading birds- juvenile reddish egrets starting to molt into their attractive blue and pinkish-red feathers. Don mentions that they sometimes have a white phase, which we saw at The Nature Conservancy’s Phipps Preserve a couple of years ago.

We hear black skimmers making their barking noises, and a dozen or so take off and circle the pond. Don checks to see if any are banded; if so, he would report the sighting.

It’s almost 8:30 am, so we’re not much past high tide. “You come back here in another three hours, and most of these birds will be gone. They’ll have moved out to the coast. And just before the next high tide hits, if you stand here, flocks of birds will come flying in.”

The final shorebird count

We make one last stop at a spot overlooking wide sand flats. Don’s birding scope sees further than my camera, and he spies far off willet, black-bellied plovers, marbled godwit, ruddy turnstones. He tallies his counts for the day. “We’re somewhere between 500 and 600 birds, which is about normal for this time of year.”

Having done this for four years, Don has a good numerical handle on how bird populations ebb and flow throughout the year.

“By the end of June, all the migrants are gone. We have our breeding birds, and a few non-breeding birds that are oversummering. But you might have 200, 300 at most. By the time we get to winter, we’ll have 3,000 shorebirds out here. And at that point, I will be counting dunlin by the hundred.”

The numbers help tell a story, and trends over time and across the region could influence future management decisions in the National Wildlife Refuge system. But numbers are only one part of that story. After spending a morning with Don, I really enjoy taking in his observational knowledge, gained by showing up before sunrise, and from decades of walking the levees.

I recommend reading his birding reports on the Friends of the St. Marks Wildlife Refuge web site. In addition to telling you what birds he sees, he describes their behavior, and the sights and sounds of the day. It’s a good way to get a feel for what you might see if you visit the refuge- or a nice escape if you’re stuck at your desk.

Visiting the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge

As of the writing of this post, the Refuge is open but the Visitor Center and Lighthouse are closed in order to prevent the spread of COVID 19. For up to date information on closures on the Refuge, check the Friends of the St. Marks Wildlife Refuge web site.

That site also has a map and additional information on Refuge trails. The trails include the levees, allowing access to the ponds for bird watching.

If you want to time your bird watching with the tides, check the gauge at the mouth of the St. Marks River. Don Morrow looks for high tides of at least 2.5 feet; this is when shorebirds leave the coast for the ponds.

Not all birds on the shore are shorebirds

As we see in the video, birds of all different shapes and sizes make use of coastal habitats. But not all of them are what birders would classify as shorebirds. Charadriiformes are an order of birds which include plovers, sandpipers, oystercatchers, American avocets, and black-necked stilts. We often see them intermingled with longer legged wading birds, such as herons, egrets, bitterns, wood storks, ibis, and roseate spoonbills. The lone flamingo that has been visiting the Refuge is also a wading bird. We may also see shorebirds together with gulls and terns on sandbars or sand flats. And swimming off the coast, we see ducks and other swimming birds, such as loons, grebes, and cormorants.

What Did We See in the Video?

We visited the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge at a time of transition. Not only are birds migrating to and from the north Florida coast, but they are also molting out of their breeding plumage. Sharper, more distinct patterns help males stand out to females in the spring and summer breeding season. In the winter, the same shorebirds tend to be a uniform grey or dull brown color, which makes them less distinct to the eyes of predators. The survey we tagged along for came as many birds were still in between breeding and winter plumage.

As always in this section, we’ll start at the beginning and identify what birds we saw at what time in the video, showing a few photo highlights along the way.

Video Intro

00:00 Greater yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca). The greater and lesser yellowlegs look almost exactly the same. The differences are size and that the greater has a bill longer than its head, whereas the lesser’s has a length about the same as the diameter of its head.

00:04 After I parted with Don, I walked up and down the shore behind the Saint Marks Lighthouse, where I found a few shorebirds and wading birds. Where a section of salt marsh has died back, we see two larger birds among the smaller sandpipers: ruddy turnstones (Arenaria interpres).

00:10 One juvenile reddish egret (Egretta rufescens) chases another in Tower Pond. As they molt, the faint pinkish grey of their necks will become brighter.

00:37 Tricolor heron (Egretta tricolor) in the marsh behind the lighthouse.

Stony Bayou I

01:56 Three blue-winged teal (Anas discors) take off from a muddy, grassy area where we see several shorebirds.

02:26 A lone willet (Catatrophorus semipalmatus) grooms itself in shallow water.

Tower Pond

03:08 In order from largest to smallest of the crowd of birds we see: Yellowlegs, short-billed dowitcher (Limnodromus griseus), which are more of a brown color than the other birds, and a small sandpiper. Small sandpipers are also known as peeps, several species of the Calidris genus that look very similar. According to the Sibley Guide’s section on peeps, the ones most likely on open coastal mudflats would be western or semipalmated sandpipers.

03:11 Juvenile reddish egret climbs onto a log. The loose feathers and white flecks make me think it’s molting.

03:15 Black skimmers (Rynchops niger) in flight, landing at the edge of a mud flat.

Back to Stony Bayou II

04:23 Saltmarsh sabatia (Sabatia stellaris) in the marsh next to the levee, opposite of the pool.

Around the Saint Marks Lighthouse

Behind the Saint Marks Lighthouse is a long beach lined with salt marshes. Here, you may find many of the same birds as on the mud flats, but other birds are better suited to picking invertebrates out of sand than mud. Seagrass wrack washes up onto the coast and decomposes over several months. It offers shelter to invertebrates, and you’ll often see plovers and sandpipers pecking at it.

A row of trees separates the shore from large sand flats and marshes. Here, again, you’ll find a mix of the birds we’ve been seeing along with a few different species.

04:50 Several peeps pick through seagrass wrack while a juvenile yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) walks on the sand behind them.

04:52 The night heron is now in a tree. I think I frightened it with my camera and tripod, and it sought a safer place.

04:54 A tricolored heron walks through marsh cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora). The salt marsh is an estuary ecosystem, full of the small fish eaten by tricolored herons.

04:59 A great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) sits perched on a dead shrub at the edge between needlerush and a sand flat. After I parted with Don, he called me to tell me about this owl out in the open during daylight hours. Perhaps there’s prey hiding in the needlerush?

05:02 A flock of white ibis (Eudocimus albus) feeds in the low lying marsh plants behind the lighthouse.

Shorebirds on the WFSU Ecology Blog

The north Florida coast is a patchwork of different coastal habitats, each with different shorebirds adapted to nesting and feeding in and around them. Snowy plovers nest in bare patches alongside sand dunes that are open, but near vegetation. Oystercatchers and least terns nest on small, flat islands near the coast. And for oystercatchers, of course, the islands would need to be near oyster reefs.

The one footed snowy plover we see here was photographed at The Nature Conservancy’s Phipps Preserve, on Alligator Point. This kind of long strand of beach, like on St. Joseph Peninsula or the tips of our barrier islands, are critical shorebird habitat.

Citizen Science on the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge

Don Morrow collects data for the US Fish and Wildlife Service as a citizen scientist. The Refuge asked Don to undertake these surveys because of his considerable experience. Those of us who are less experienced, though, can also collect data as citizen scientists using apps and programs designed for naturalists of all levels.

iNaturalist is a free app that helps you identify any plant, animal, or fungi species from photographs you take. Its auto-recognition software presents users with a list of possibilities. Other users, including biologists, then confirm or recommend different identifications. Observations are added to a number of research databases, tracking everything from the spread of invasive species to occurrences of rare flora and fauna.

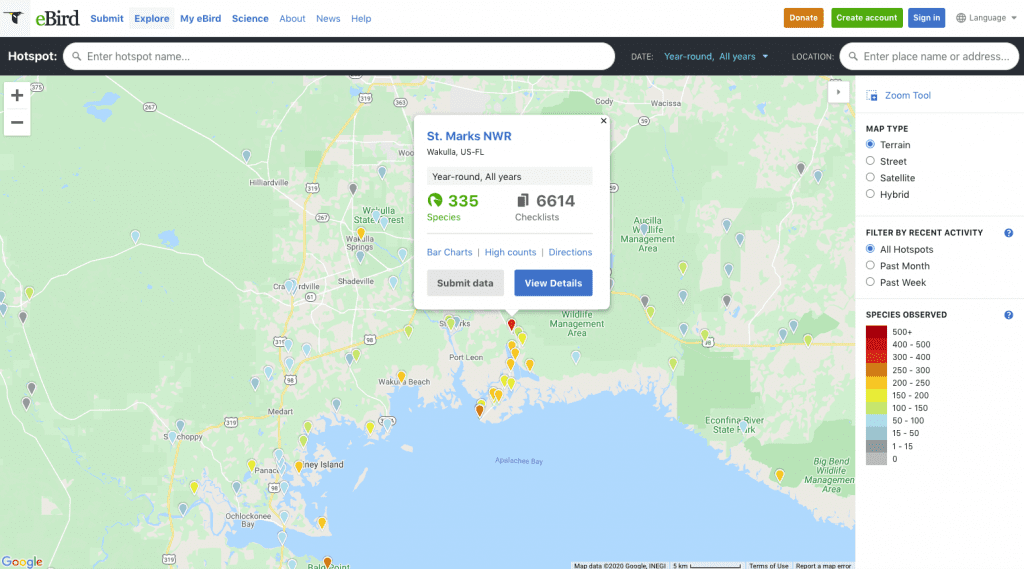

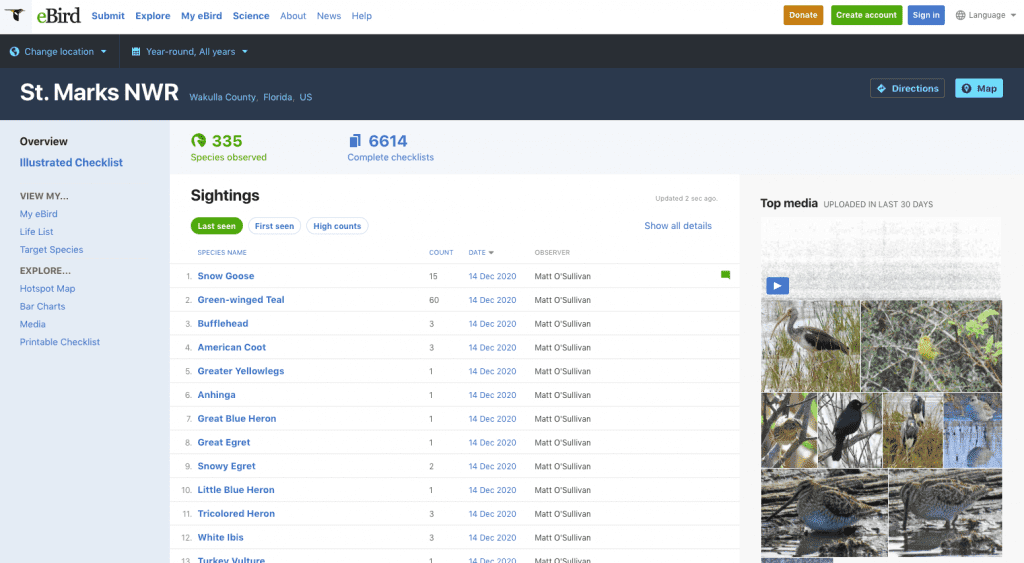

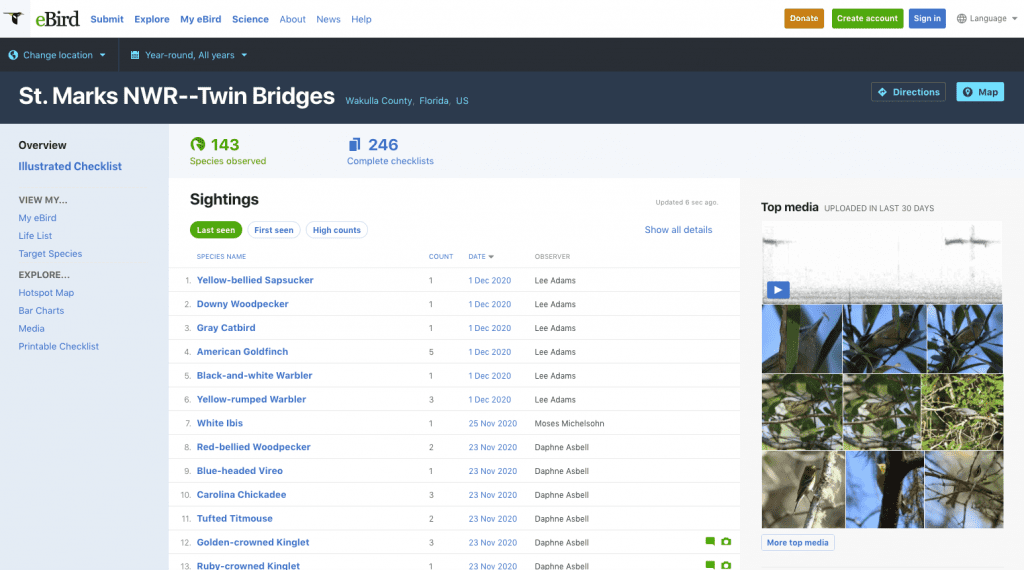

eBird is an app that is better suited for a somewhat experienced birder. Maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, eBird collects data on birds that adds to our knowledge of their migratory patterns, seasonality, and species range. eBird is also a good way for a user to learn about where birds have been sighted in a specific area, either recently or over time. Check out the hotspot map for the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge to see what species have been seen where, and when.