The little coral snake slithers onto a bed of reindeer moss, its bright reds and yellows popping against the pale green. A few of the biologists and zoo representatives gathered today mention that the snake is on their life lists; soon, the sky above it crowds with cameras. In a couple of minutes, those cameras find an even younger mud turtle hatchling. And then, of course, the cute little striped newts that have brought us here today. Everyone gets to hold a pair of these rare creatures, and lower them into an ephemeral wetland in the hopes that they’ll breed and rebuild the population here in the Apalachicola National Forest.

It’s a little warm for February; outside of a couple of days that dip into the thirties, we’ve barely had a winter. Ryan Means points out bog violets growing at the edge of the wetland, mentioning that they usually bloom in the spring. Later I look up the eastern mud turtle, after we find a few hatchlings at the edge of the wetland. They usually breed in the early summer, and their eggs typically hatch in August and September.

The seasons seem a bit off right now; but then, it’s just one month in one year.

The story of the striped newt is one of seasons over several decades. That’s one reason I attend the Coastal Plains Institute’s striped newt releases every year. In addition to the different flora and fauna we see at every release, the wetlands tell us a story about the climate in our area.

Annual Ephemeral Wetland Breakdown- You Can Skip Ahead If You’ve Already Read This on the Blog

I write about these releases just about every year. To understand the story, we have to understand the hydrology of ephemeral wetlands, and how the striped newt has adapted to survive here. I don’t want to seem repetitive to those of you who’ve read my previous posts. I give you my blessing to skip the following section. Below that, we’ll dig deeper into the relationship between the fullness of the ponds and our drought cycles. We’ll also talk to Ryan Means about the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to not to federally list the striped newt. And we’ll have more pics of the cute animals we saw. Such as: look how many newts this woman decided to release all at once!

Striped Newts in the Munson Sandhills | Climate Indicators for Leon County, FL

Ephemeral wetlands in the Munson Sandhills go dry, and that’s okay. They’re dry now, even lower than they were for the 2018 release, which at the time was the driest I’d seen them. Between the 2018 and 2020 releases, the wetlands briefly became so flooded that several nearby ponds connected to form one giant wetland.

Their fullness reflects the level of the aquifer beneath them. There’s still a lot that’s mysterious about our groundwater, the source of our drinking water and springs. But in the places where it interacts with and becomes surface water, we gain insight as to how water moves beneath the surface. Ephemeral wetlands give us some indication of how much rain it takes to raise the water table.

One of the things I love about the salamander stories I’ve done with the Coastal Plains Institute and with their recently retired founder, Dr. Bruce Means, is how tied the animals are to geology. The underlying soils and rocks form different wetlands: seepage slopes, steephead ravines, ephemeral wetlands. Different salamander species have evolved to thrive in each of these different places. For striped newts, that means changing themselves to live outside the pond, in the longleaf forest, when ephemeral wetlands go dry. When the water level rises again, they metamorphose into an aquatic form and return to breed.

But what if the water doesn’t return?

That’s what happened in the 1990s. An extended drought in north Florida kept the wetlands dry for several breeding cycles. Adults died off, and there were no children to replace them. They went from inhabiting 20 ponds in the Apalachicola National Forest to just one.

Ephemeral Wetlands and Drought | How Much Rain Does It Take to Fill One?

The fullness of our ephemeral wetlands is tied to our cyclical dry and wet periods. It all starts in the eastern Pacific Ocean, where years long cycles of cooling and warming water affect wind and rain across the globe. Warmer waters in the eastern Pacific mean more rain in the American southeast, while cooler waters there mean an overall warmer and drier climate here.

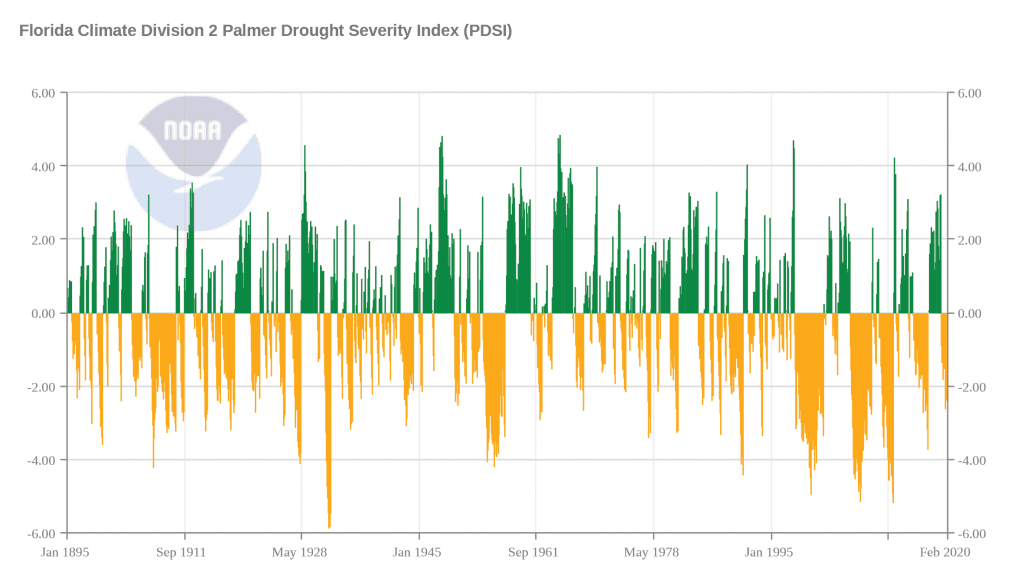

I generated the chart above using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Time Series tool. It shows the state of drought in all of north Florida east of the Ochlockonee River- Division 2. You can see that the cycles are not regular, and that there have been prolonged wet and dry periods. Looking more closely at the right side of the chart, you can see that our drought periods have been long and intense in recent decades, and our wet periods not as wet.

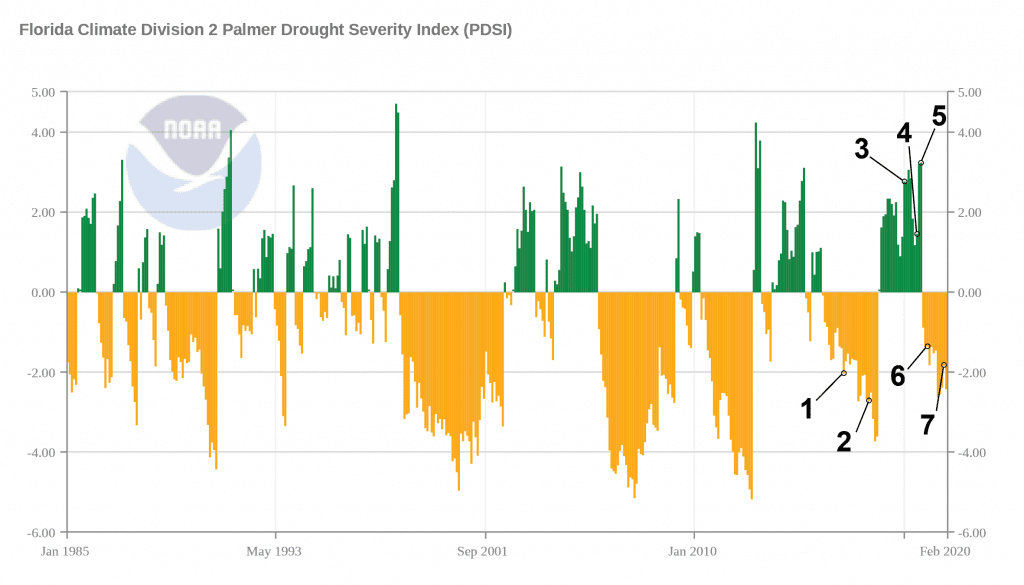

Below we zoom into that period with a graph looking at droughts in our area between 1985 and February 2020.

Striped newts all but disappeared from the Munson Sandhills during the 1990s. This region of the Apalachicola National Forest is just south of Capital Circle in Tallahassee. Wakulla Spring lies to the south; its springshed (the area from which its waters enter the aquifer) ranges from Tallahassee to Thomasville, Georgia. Both the spring and these wetlands give us some indication as to the state of groundwater in our area.

From recent, informal interviews with groundwater researchers at FSU, I can share that they’re not concerned about our drinking water supply. The Floridan Aquifer is one of the largest in the country, and it is deep. But ecologically, we have seen effects of depressed groundwater resources on these wetlands, Wakulla Spring, and our sinkhole lakes.

With that in mind, I marked the chart above with several of my visits to ephemeral wetlands in the Munson Sandhills starting in January of 2016. Looking at drought and precipitation information during this time, you can get a rough sense of what it takes to fill these wetlands.

1. January 2016 | My First Striped Newt Release

Here, we’re a few months into a drought period. I don’t want to say this is “average fullness;” after all, fullness is always in flux here. But you see that there is a sizable pool of water reaching almost to the encircling drift fence. It’s normal for these ponds to have vegetation like this, and in fact, the species that inhabit the ponds need it. During dry periods, fire will clear it out just as it does in the understory of the surrounding longleaf forest.

2. January 2017

One year further into the same drought period, and we can no longer see the puddle of water from the edge of the pond.

3. June 2018

Here’s where it starts getting interesting. Using the Palmer Index, one drought period ended in May of 2017. But by January 2018, Ryan and Rebecca still didn’t feel they had enough water to release newts.

By June, they felt they had enough rain had pooled in their ponds for a release. They’ve lined the three recipient ponds into which they release newts, so water doesn’t drain directly into the underlying limestone. So the striped newt ponds are a little fuller than nearby ponds.

Of course, winter is when striped newts breed; so in June, they released late-stage larvae rather than the usual breeding adults. In their aquatic larval stage, they were able to imprint on the wetlands, and hopefully return to breed. But they’d also metamorphose soon after, and leave a pond not guaranteed to hold water for much longer.

The photo above is of a reference wetland near a release pond. The Coastal Plains Institute uses this to see what their wetlands would look like without the linings they installed. This one was bone dry, but that’s not necessarily bad. A wildfire came through and killed back the plants in the pond, which is beneficial for the animals who use it. Otherwise, the vegetation would become too thick.

You can see that pine trees were among the plants burned by the fire. Pine trees encroaching on the wetlands is a sign of extended droughts. If this fire, and the floods to come, didn’t kill these pines, they’d become established and begin to shade out the wetland, changing its ecology.

4. November 2018

A few months later, the wetlands weren’t much fuller. This is not a striped newt recipient wetland, but one not too far away. Rebecca Means was hosting an Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland group from the Palmer Munroe Teen Center, and she was checking out their pond ahead of time. Rebecca was, at this point, realizing that they’d have a tough time netting the pond in search of amphibians. Instead, they spent more time exploring the surrounding upland forest.

5. January 2019

Just two months later, everything was much wetter.

Here’s the thing about the photo above. They’re standing towards the edge of what is usually the wetland basin. The water behind them is stretching out into the next wetland. Two lined ponds and three unlined ponds formed one larger than usual basin, including the totally dry wetland we visited six months earlier. This was the very last month before we entered drought conditions again.

6. April 27, 2019 | EcoCitizen Day

Three months later, the water levels were again lower. Here it’s ankle deep at the edge of the wetland. This is another of the unlined wetlands adjacent to two lined wetlands.

7. February 2020

And finally, the most recent release. A year after the wetlands flooded into one another, this is the lowest I’ve seen it since I started coming out. This is a lined wetland, and fuller than surrounding ponds.

Now Lets Look at Rainfall in Inches

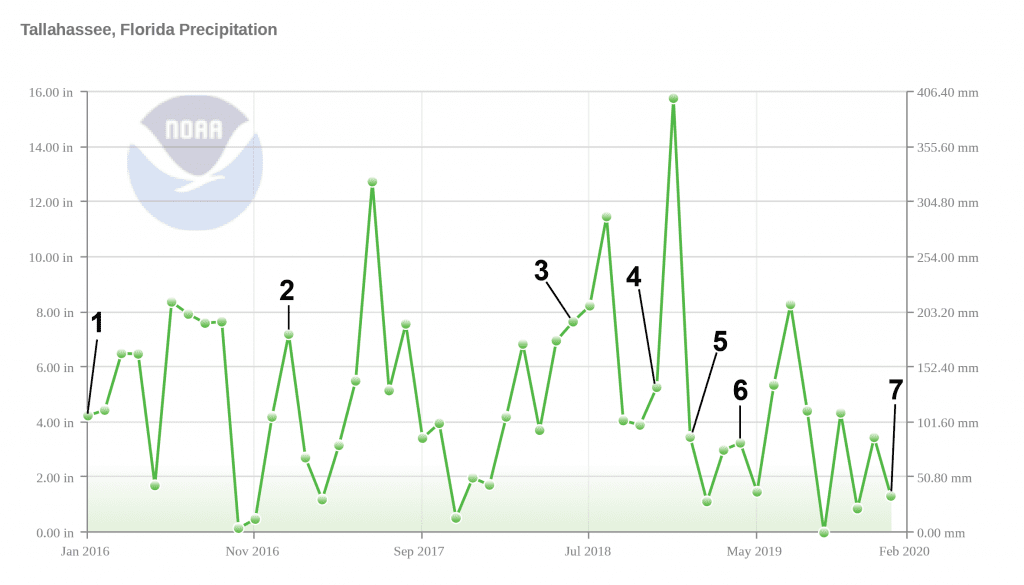

The Palmer Drought Severity Index measures prolonged moisture or dryness in a given region. It’s also looking at climate regionally, and not locally. The NOAA time series tool lets us look at rainfall by city. So, out of curiosity, I wanted to see how Tallahassee’s rainfall corresponded to the scenes we’ve just shown.

You can roughly see our normal wet and dry periods throughout the year; Low points in the fall, and two rainy periods in, more or less, late winter and early summer. Every year is different, and even in the dryer years, there are these peaks and valleys of more and less rain.

The largest spike on the chart is December 2018, one month before the wetlands were flooded. This was one last deluge after months of steady rainfall. Even the dryer time of that year had about four inches a month.

It had rained steadily for months before we went in June 2018 and saw a bone dry, fire scarred wetland. Eleven inches in August didn’t do much to fill wetlands in November. All this time, the limestone aquifer was saturating, inching the water table closer to the surface and just over it. By the time sixteen inches rained down in December, the limestone beneath the sandhills was already soaked.

In January, we sloshed around in and around the wetlands. In February, our Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland group, consisting of my family and a couple of others, couldn’t walk more than a dozen feet or so into our overflowing wetland before the water was up to our armpits. But then, by April 2019, we saw how quickly water moves beneath us. Into springs, out of our taps, through underground channels barely mapped. Groundwater disperses, and the water table lowers again.

These four years, the way I’ve presented them, are a snapshot. It gives us a visual representation of what we see in the charts. We see that it can take a lot of rain to top off the aquifer beneath the wetlands even after a long, harsh drought has ended. And long, harsh droughts have become normal here.

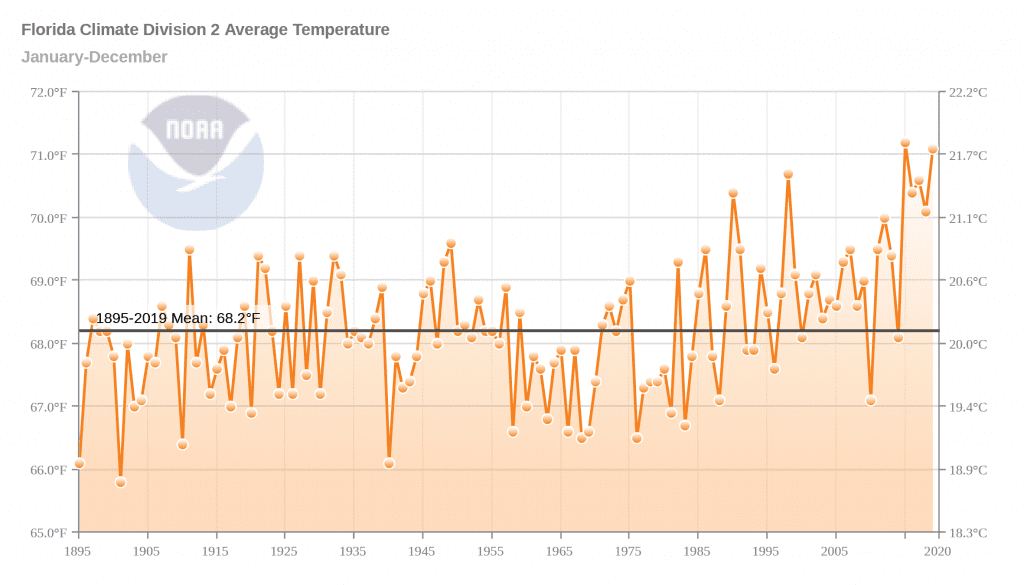

One last chart to share from NOAA’s time series page. It’s 125 years of average temperatures in north Florida.

Striped Newts and the Endangered Species Act

“The striped newt has always been a globally rare species,” says Ryan Means. He’s the President of the Coastal Plains Institute. “It has only ever been known from 120 or less wetlands over the whole course of time that humans have known about the species.”

According to research conducted by C. Kenneth Dodd Jr., D. Bruce Means, Steve A. Johnson in the early 2000s, striped newts had, as of then, been found in 116 wetlands split between two distinct populations. These populations are separated by over 75 miles, and are genetically distinct. The likely reason for this separation is habitat loss; at one point there would have been more or less continuous longleaf habitat between the panhandle/ south Georgia population (Western Clade) and the one in central Florida (Eastern Clade). This had likely once been a more widespread species.

According to that study, the entire species’ range had been reduced to fifteen known locations, areas with clusters of breeding ponds. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission then conducted a statewide survey between 2005 and 2007, finding newts in 28 ponds in nine locations on public land. The animal appeared to be in serious decline.

In 2008, the Coastal Plains Institute petitioned the US Fish and Wildlife Service to federally list the striped newt as Threatened. It was a lengthy review process. “That’s always a process to go through,” Ryan says, “and it should be.”

After ten years of review, in December of 2018, the answer came.

“Based on the best available information, we find that the striped newt does not meet the definition of an endangered species or threatened species.”

US Fish and Wildlife Service, December 19, 2018

Should the Striped Newt be Federally Protected?

“It was a big surprise when the US Fish and Wildlife Service ruled not in favor of listing the striped newt as Threatened.” Ryan says.

There were two main reasons that striped newts were not listed. One was the discovery of new breeding ponds, including one at the Dixie Plantation in Jefferson County, Florida. And while the newt was thought to have been extirpated from the Munson Sandhills, they’ve been recently found breeding in one pond there, adding local genes to the breeding program upon which Ryan and Rebecca rely. That, plus a couple of locations in southwest Georgia, is the extent of the western population. The eastern population is more robust.

Another reason for not listing was that, in the eyes of the USFWS, Ryan and Rebecca have been too successful with their striped newt program: “Additionally, past conservation efforts, including captive rearing and release of striped newts, have helped reestablish striped newt populations in previously extirpated areas, such as in the Apalachicola National Forest.”

“I am the leader of the Striped Newt Project, and I disagree with that notion.” Ryan says. “We have certainly had some success here, and we’re proud of it. But we’re nowhere near successful enough yet.”

So, how do you measure success?

Ryan and Rebecca have captured marked adults returning to the ponds to breed. They mark newts before releasing; it’s a painstaking process, and they release hundreds of newts during every event. You can read about how they mark newts in this post from 2016. Anyhow, they know that some of their released newts are surviving.

They’ve also captured a few unmarked newts leaving wetlands. Drift fences encircle release ponds, and there are traps on both the inside and outside. When newts try and return to breed, they hit the fence but they keep trying to find a way in, so they move along the fence until they fall into a trap. The traps are checked daily, and any animal trying to get in is then placed on the inside. Animals trying to leave are placed on the outside.

Those unmarked newts leaving the wetlands are the Striped Newt Project’s biggest measure of success. These were born in the wetland, and not in a zoo. Right now, though, Ryan and Rebecca have only found a handful of these wild born newts. The question is, if the Coastal Plains Institute stopped their yearly releases, would the population in the Apalachicola National Forest continue to grow without human assistance?

A few years ago, we took a field trip into an old growth longleaf forest with Tall Timbers ornithologist Jim Cox. He was touting the success of artificial nest cavities in rebounding red cockaded woodpecker numbers. Someone asked him if that meant that the bird was ready to lose its Endangered status. His answer was that until the bird has enough longleaf pine trees of at least 90 years of age, woodpeckers would not be able to build more of their own cavities. And so they’d still be reliant on humans to have places to lay eggs and raise young.

Striped newts in the Apalachicola National Forest are benefiting from lined wetlands, just as RCWs benefit from artificial nest cavities. And breeding ponds receive a yearly influx of over a hundred captive bred individuals. This sounds like a lot, but the forest is full of predators. This is a species that lays hundreds of eggs at a time because there are so many things that kill them; if two of those eggs become breeding adults, then they can replace their parents and maintain a stable population. Of course, Ryan and Rebecca aren’t looking to maintain, they’re looking to grow the population.

What’s Next for the Striped Newt?

A federal listing would have added considerable resources to the striped newt repatriation effort. The project currently benefits from a network of partnerships: zoos, nonprofits, and state and federal agencies, all spearheaded by the Coastal Plains Institute. This is a two person operation, not including the volunteers who help check drift fence traps throughout the year. Perhaps it seemed to the US Fish and Wildlife Service that the project had all it needed. But, to Ryan Means, the resources that come with a federal listing would have given the animal the highest level of protection.

“The really cool thing about the Endangered Species Act is that every species, save for maybe one out of hundreds of species, has either been rehabilitated back to relative health, or has yet to go extinct.” Ryan says. “It’s one of the, if not the world’s greatest conservation policy that any country ever came up with.”

The Coastal Plains Institute may try to reapply for federal listing. In the meantime, there has been a hopeful development at the state level.

“The state of Florida is moving to begin a listing process for the striped newt,” Ryan says,”because Florida contains most of the localities for both the western and the eastern populations of striped newts.” The striped newt is already listed as Threatened in Georgia.

What Else Did We See?

Every time we visit a striped newt pond, we see different animals in and around it. On my second striped newt release, we saw ornate chorus frogs. One time our Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland group went to check drift fences, and we saw gopher frogs. After last year’s release, we saw red cockaded woodpeckers, and the year before, Ryan caught a banded water snake in a wetland (both releases are in the same video).

This year, the coral snake and several mud turtles provided some highlights.

Ryan and I found this one a couple of days after the release. I wondered if it might have been one of the turtles we’d seen earlier. One way to tell is the plastron- the underpart of the shell. Each mud turtle has a different pattern.

Looks like two different individual turtles. Its scientific name is Kinosternon subrubrum; subrubrum means reddish underside. As we see, the orange/ red color fades as they get older:

Here’s a look at the top of the shell. Someone was feeling shy:

Ryan also netted up a southern leopard frog:

And of course, one of my favorite animals to photograph is a wolf spider:

They sit nice and still and let me get my macro right up to them. The first time I tried to use iNaturalist to identify one, the suggestions were all mammals, including an actual wolf. I think it’s the hairy texture captured in macro mode.