Ephemeral wetlands have remarkable amphibian life within them. But, as we’ll see, the life around the wetlands is equally amazing.

Saturday is EcoCitizen Day, where you can observe wildlife at Lake Elberta and here in the Munson Sandhills. And then Monday, you’ll want to watch PBS Nature’s three night American Spring LIVE (April 29, 30, and May 1 at 8 pm ET on WFSU-TV). EcoCitizen was made possible by a grant from PBS Nature, and is sponsored by the City of Tallahassee. Additional support has been provided by Leon County and Proof Brewing Company. EcoCitizen Day is a part of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Tallahassee/ Leon County City Nature Challenge.

We’re offering field trips to the Munson Sandhills for EcoCitizen Day. The trips are free, but you have to register ahead of time.

Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog to receive more videos and articles about our local, natural areas, and subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Youtube Channel.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

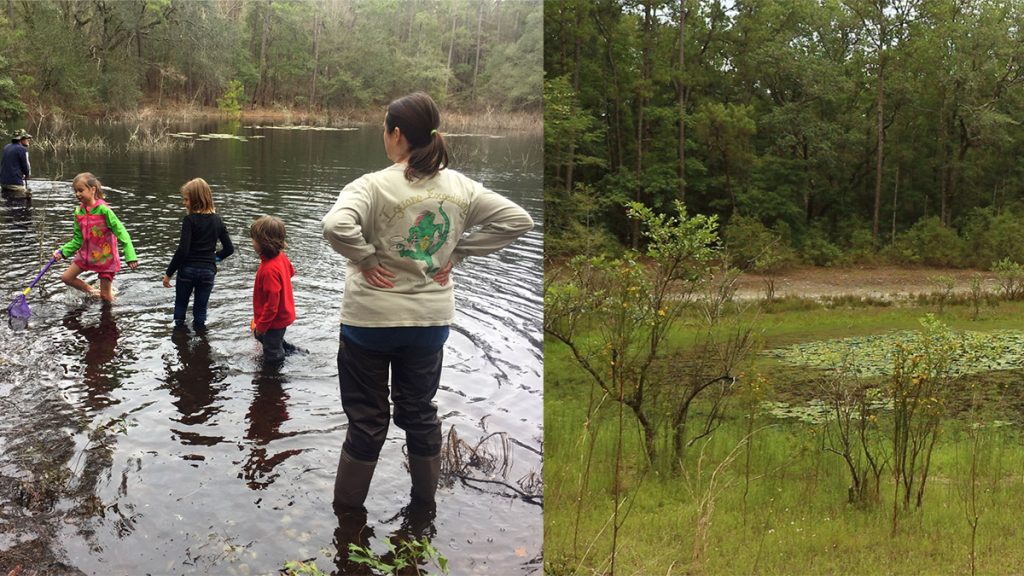

For a video on dipnetting for amphibians, it felt like I spent a lot of time on animals other than salamanders and frogs. Of course, we do see the barking tree frog tadpole, and a few others. And we see kids playing with cricket frogs. But as we’ll soon see, the true value of the Coastal Plains Institute’s Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland Program is greater than just the critters at the center of it.

For instance, on EcoCitizen Day (this Saturday, April 27), the wetlands will be a bit lower than you see in most of the video. Lower, but not bone dry as they were in the summer. No, the dynamic nature of these ponds isn’t something you can see in one visit. But it means that the plants and animals you see in and around the wetlands are always changing. Over time, you see quite a diversity here.

Rebecca Means has selected a striped newt repatriation pond for the event. That means that, in addition to dipnetting the ponds, participants be able to check drift fences around the wetlands. When you watch videos of past striped newt releases, you can see just how many different critters end up in their drift fence traps: turtles, frogs, scorpions, tiger beetles, wolf spiders… It sounds scarier than it is.

And then a few feet away from the pond, there’s the longleaf pine forest. Flowers are in bloom, and insects are pollinating them. Oftentimes, the birds are high up in the canopy, so you need binoculars to see them. Or, like during the last striped newt release, an endangered red cockaded woodpecker might decide to peck lower down on a nearby tree, where they’re a little more visible.

Ryan and Rebecca Means, and their volunteers, will be there to help point out animals to you. There will be plenty of observations to be made on iNaturalist, to help us win the City Nature Challenge. That’s part of why I wanted this to be a location on EcoCitizen Day, because I wanted Tallahasseeans to realize how close by this forest is to them.

City Nature Challenge and Citizen Science

The Munson Sandhills region of the Apalachicola National Forest is just south of Capital Circle. It is, in fact, in Leon County. That means that any iNaturalist observation made here between April 26 and 29 counts for the Challenge. Any species observation made anywhere in Leon County gets us closer to beating out 170 other cities across the world.

The point of the City Nature Challenge is to observe as many species as possible within your city’s area. I love this, because it gets you thinking about where life is in relation to you. On the morning of April 26, the monarch caterpillars in my yard should be a nice size. I’ll likely make them my first observation. Those weeds that I’ve used iNaturalist to identify- I’ll observe some of those as well. Maybe I’ll wake up early enough to get a dozen or so observations before I leave for work and help the team make final preparations for EcoCitizen Day.

On Saturday, I counted 16 first instar monarch caterpillars on my milkweed plants. How big will they be on Friday?

All throughout this weekend, insects, squirrels, and birds will pass through your yard. Once you start paying attention to them all, you’ll be surprised at just how many plant and animals species are around you every day. If you walk down to your closest city park, you’ll find much more to observe.

EcoCitizen Day is the biggest Tallahassee/ Leon County City Nature Challenge event. It’s your chance to visit a couple of places full of wildlife, and do so with biologists and iNaturalist experts to guide you.

Everything starts at our headquarters on FAMU Way, next to the Railroad Square Playground. There will be activities for kids and adults, PBS KIDS Nature Cat, music, and author readings. From there, it’s a short walk to Lake Elberta. We’ve covered this remarkable location over the last few months– it’s an unlikely wildlife hot spot. Apalachee Audubon will be there to help you spot the birds, pollinators, and other critters that call the park home.

From headquarters, you’ll also be able to catch shuttles to San Luis Park, and to the Munson Sandhills. In a second, we’re going into more depth on the Munson Sandhills. However, you can click here to see a full list of City Nature Challenge events.

Citizen Science | Fun and Easy to Do?

At the center of the City Nature Challenge is the iNaturalist app. This is an app whose information can be used in various citizen science programs, so it seemed like a natural fit to partner with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission for what they were planning to do with the Challenge. After all, one of the EcoCitizen Project’s main missions is to get people to engage with citizen science.

And while we’ll be having a field day with iNaturalist in the Munson Sandhills, we also wanted to feature ongoing citizen science in the form of the Adopt an Ephemeral Wetlands Program. Rebecca and Ryan run a two person research and conservation organization, the Coastal Plains Institute. They study over 150 ephemeral wetlands in the Munson Sandhills, and they spearhead a multi-organization effort to reintroduce the striped newt to its historic wetlands. That’s a lot for two people to do.

Enter our local citizen scientists.

The citizen science movement helps professional scientists by providing free help in collecting data for research projects. People sign up to do this because they care about the research, but there has to be a greater motivator for them.

“This is one of the things with citizen science projects is that, you have to meet your objectives for data gathering,” Rebecca says. “But you also have to make sure that it is easy and fun for people to do.”

You see some of the program’s participants in the video. A toddler. Teenagers. They splash in the water. They run in the woods. Just last week, after this video was produced, the Palmer Munroe Teen Center kids returned to their pond, and Rebecca had them drawing tadpoles and forest scenes.

The primary mission is to survey the pond and report data. For those of us who are doing this with our kids (like me), our goals are more closely aligned to learning to love the forest through our visits. And then there’s another benefit of being a citizen scientist- what you learn by participating.

In the case of Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland, you learn best after repeated visits.

In and Around Ephemeral Wetlands, Season by Season

Over the past year, I’ve visited several wetlands during different times of the year. I’ve seen wetlands go from bone dry to flooded and back down to something more typical. As this was going on, different plants bloomed around the wetlands, and different animals went through different stages of their life cycles.

Your feel for this seasonality increases when you factor in the surrounding longleaf forest. The families in our Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland group picked a wetland that we had to hike into. All children should know what it’s like to walk through a forest. There’s just as much to see on that walk as there is at the wetland.

The following is a look at the things I saw in every season of the last year over various shoots and family field trips:

Summer 2018

It was a dry winter and spring, and so we missed out on dipnetting our wetland, and CPI couldn’t do their normal striped newt release in January. There was eventually enough rain to release newts in June. And I ended up visiting my family’s wetlands in June as well, when I wanted to test a new piece of equipment. So I got to see the wetlands during a different time of year than I normally visit.

Walking into our wetland, I passed a flowering butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) plant. I didn’t see any monarch caterpillars on it, but a cloudless sulphur was enjoying the flowers. I ended up using video of that sulphur in our recent piece on native milkweed species. As master milkweed hunter Scott Davis says in that video, different milkweed species bloom at different times of year. By June, the monarch migration is in full swing, and the forest is full of blooming butterfly weed and sandhills milkweed (Asclepias humistrata) plants to feed them and their larvae.

After bushwacking through the smilax covered tangle between the trail and one wetland, I see more color than I’m used to here. Bumblebees are buzzing around yellow flower covered shrubs (02:28 in the video). This is common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), an invasive plant introduced from Europe.

On the ground between the St. John’s-wort, I see little pink flowers (02:30). According to iNaturalist, these are meadowbeauties.

A dark shape moves over a white flower (02:33). It’s a type of skipper, those nondescript little brown butterflies, on a buttonbush flower. Thankfully I can zoom in and see the spots under the wing, and the pattern over top. This is a Horace’s duskywing (Erynnis horatius).

Horace’s duskywing (Erynnis horatius) on buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), a native coffee plant.

A couple of weeks later, The Coastal Plains Institute releases striped newts into a nearby wetland. I wrote up their finds, and some interesting seasonality regarding newts and their breeding, this past February.

Fall 2018

One November day, I decided to do some camera training in the Munson Sandhills. Carlee Soeder had recently been assigned to me to help with the EcoCitizen Project, and I wanted her to be familiar with the camera as well as with our featured locations.

Walking along the trails to the striped newt release ponds, we saw members of the aster family in various hues. I was still new to iNaturalist, so while I got so many good closeups of flowers, I didn’t get all of the other photos that help knowledgable plant people make IDs.

This is how I photograph flowers now: I take two to three photos of the flowers you see- 1. Flower closeup, 2. One where you see leaves, 3. One more zoomed out where you see some perspective (is it a shrub, a single flower, etc.). Sometimes I take one with my finger in it, for scale. That can be helpful with the small ones, to show how small they are.

So I don’t have as many flower IDs from this day as I’d like. And anyhow, there are so many similar asters, you don’t always get an ID. I did learn that the purple one on the right is a Scaleleaf aster (Symphyotrichum adnatum).

We also saw a slender blazing-star (Liatris gracilis). Blazing-star species tend to start blooming in late summer and through the fall. So it’s a good seasonal indicator.

And after seeing some cool beetles during the striped newt release over the summer, we encountered this smooth ox beetle (Strategus antaeus). Dean and Sally Jue once told me that many of the people who get into butterfly watching start as birders, and that many of them also get into beetles and dragonflies. Visiting the Munson Sandhills on these shoots, I can see why.

Winter 2018/ 19

When it did rain, it really rained.

Sitting at the edge of the Palmer Munroe Teen Center pond in January, we sat and watched a migratory duck, a bufflehead, swimming around. Perhaps, with it being duck season, it found a nice sized water body where hunters wouldn’t be looking for it.

Walking away from the wetland, most of the wildflowers we saw had gone to seed. One or two stragglers were in bloom, though.

It was a warm January, overall, with waves of cold falling just short of a hard freeze. Carlee spotted this pygmy rattlesnake coiled between oak shrubs and palmettos.

Later that January, CPI released striped newts into over-full wetlands. I wrote about that in February, but what I didn’t mention was how five different wetlands flooded to the point where they were connected, and were, for a short while, one. This includes a wetland we visited last summer, which had no water, and burned in a May wildfire.

That fire zapped several pine trees that had encroached on the wetland basin while it was dry. In January, these dry-environment trees were flooded. This is how nature maintains the wetland, cycles of fire and flood help weed out plants and determine what goes where. With all of that activity, you can imagine that the boundaries between the wet and dry environments is always changing.

We saw this in earnest during a March dipnetting day.

March Dipnetting Days

Rebecca Means often trains new citizen science volunteers in a wetland just off of Crawfordville Highway. Over the last few months, she’s been holding monthly dipnetting days, which are part training, and part commitment-free tryout for individuals or groups curious about the program.

On the March 2019 dipnetting day, this training wetland was still flooded. Several dozen young pines stood directly in water. And several that were still in the grass stage had flat out died.

It was a prolific day for finding amphibian larvae, as well as dragonflies and damselflies in various life stages.

Rebecca was placing her finds in a clear aquarium, where we saw a dragonfly larva eating a damselfly larva.

After dipnetting ended, my production assistant Taras showed us where a hawk looked to be making a nest in the distance. Walking away from the wetland, we saw a couple of colorful flowers blooming between the pines.

The first was lady lupine (Lupinus villosus). I had just seen this a few days earlier at a frosted elfin site not far from here, growing alongside sundial lupine.

And also candyroot (Polygala nana) was starting to bloom. Soon after, this flower would have reached full bloom and turned bright orange. I like the photos EcoCitizen intern Nick Carlson took of these flowers.

The month before this, our group of families visited our adopted ephemeral wetland. We hadn’t dipnetted our wetlands in almost two years, though I did sneak in that visit over the summer. We’d seen the pond shrink gradually between our first and second 2017 visits, and it got even smaller over the summer of 2018. In March we saw a small lake.

All the buttonbushes and other shrubs reached leafless branches out of water out at the center of the pond. We found mole salamander and gopher frog larvae, but not the ornate chorus frogs we’d seen so many of two years ago. So much of the pond was inaccessible- we were up to our waists within a few feet of the current shoreline. While a lot of amphibian larvae can be found at the edge of a wetland, where recently inundated vegetation offers shelter and forage, there was just a lot of wetland that we couldn’t net.

Spring 2019

In April of 2019, the Palmer Munroe Teen Center kids returned to their wetland. They never had a day here when the pond was flooded, and by now the water level was much closer to what it had been in the fall.

iNaturalist helped me identify two different grasshopper species:

Off one corner of the wetland edge, blueberries were flowering. If the Palmer Munroe group came back to dipnet their wetland in June, Rebecca told them, they would have a little treat.

Rebecca had them try one of the citizen science programs that will be featured on American Spring LIVE, the Great Sunflower Project. Each teen watched a single flower for five minutes, and recorded any pollination of the flower. A few flies buzzed by the flowers, but for the most part didn’t take nectar. But we learned that not just bees and butterflies pollinate. Flies, beetles- many insects are attracted by the sweet scent of flowering plants.

I did see one battle worn butterfly, this striking zebra swallowtail:

And there were some flowers, but not as many as I thought there’d be. This was a neat one. It was just starting to flower, and I haven’t had anyone make an ID on iNaturalist yet. The app figures this is in the aster family, genus Pterocaulon.

iNaturalist has added a fun element to my Munson Sandhills visits. We see so many different types of plants and critters, and now it’s so much easier to learn their names.

iNaturalist has added a fun element to my Munson Sandhills visits. We see so many different types of plants and critters, and now it’s so much easier to learn their names.

With the way these wetlands change, that’s helpful. The areas around these ponds go from wet to dry to damp to flooded to dry again. Factor in a fire every three years or so, and you have this ongoing cycle of destruction and renewal. When some plants burn or drown, they make space for others. A longleaf forest has hundreds of plant species, so the possibilities are limitless. Different plants will attract different insects and snakes and birds. Every visit so far has had something new to see.

Never the Same Pond Twice

I only just started coming here in 2016 for a striped newt release. The Munson Sandhills are close to WFSU, so I occasionally bring a camera to test new gear or train someone. And we’ll keep bringing our kids to their wetlands every year. Since we started in 2017, they’ve seen ponds at various shapes and sizes. Over the years, they’ll see the ponds take on a few more looks. It’ll always be a different adventure.

That’s the fun of the Adopt an Ephemeral Wetland Program. It’s an adventure a small child can enjoy, and yet there’s always something new to discover. It may be some new creepy crawly in the grass by the water, a migratory bird flying between the pines, some new species of larva in the dipnet, or a whole different patch of flowers where the ground had been underwater last month.

What might you discover if you come out on EcoCitizen Day this Saturday?

WFSU EcoCitizen is funded by Nature, a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET and PBS. American Spring LIVE is a production of Berman Productions, Inc. and THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET.

Major support for Nature: American Spring LIVE was provided by the National Science Foundation and Anne Ray Foundation.

Additional financial support was provided by the Arnhold Family in memory of Henry and Clarisse Arnhold, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation, the Lillian Goldman Charitable Trust, Kathy Chiao and Ken Hao, the Anderson Family Fund, the Filomen M. D’Agostino Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, the Halmi Family in memory of Robert Halmi, Sr., Sandra Atlas Bass, Doris R. and Robert J. Thomas, Charles Rosenblum, by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by the nation’s public television stations.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1811511. Any

opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.