UPDATE: Scroll down to see the recent good news in the striped newt repatriation project covered in this video (May 24, 2016)

The striped newt is a bridge between the longleaf pine ecosystem and the many local water bodies that connect to our aquifer. If you want to know more about other longleaf species like red cockaded woodpeckers (one of whose cavity is taken over by another species in the video below) or gopher tortoises (in whose burrows striped newts may shelter during fires), you might enjoy our recent Roaming the Red Hills series. The location of our gopher tortoise video is Birdsong Nature Center, where the stars of our striped newt adventure will be leading the first ever Ephemeral Wetlands Extravaganza this Saturday, May 21 (EDIT: This is event is being rescheduled due to storms forecasted for Saturday morning. Keep an eye on the Birdsong calendar or Facebook page for more information) .

Like in Roaming the Red Hills, original music was composed for this video by local musicians. Hot Tamale has contributed music to EcoAdventures in the past. In one of the first ever posts on this blog, Hot Tamale’s Craig Reeder wrote about their song Crystal Gulf Waters, which was inspired by the 2010 BP Oil Spill. The segment below aired on the May 19 episode of Local Routes.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Ryan and Rebecca Means put the future of the striped newt species (in the Apalachicola National Forest, anyway) in the hands of young children. They didn’t intend it to be symbolic; it just seemed like it would make for nice video. And it was. The images do, however, reflect a central mission of the Means’s work with the Coastal Plains Institute: to foster a love of our local ecosystems in the young, with the hope of creating a new generation of stewards.

Rebecca Means, of the Coastal Plains Institute, prepares to hand out striped newts to a group of young volunteers.

In January of this year, CPI released one hundred and twenty three newts into ephemeral wetlands in the Munson Sandhills region of the Apalachicola National Forest. Ryan and Rebecca brought their daughter, Skyla, and invited some friends with kids to take part. They were nice enough to let me bring my own boys, Max and Xavi, as well. Max is just about old enough to understand when I tell him that the water in these wetlands is connected to our drinking water source, the Floridan Aquifer. Ephemeral wetlands rise and fall according with the fullness of the aquifer, which is influenced by natural wet and dry climate cycles. A long drought disrupted these cycles, drying out wetlands in the Munson Sandhills for an extended period.

Striped newts are born in these ponds, but will metamorphose and climb out into the longleaf pine forest. “They spend most of their lives in the uplands as terrestrial salamanders” Ryan told a group of passing equestrians, “Eating insects, eating worms, eating whatever they can shove down their gullet.” The ability to change their bodies makes them well-suited to make use of a wetland that empties and refills. Having left the wetland, they roam under the protective cover of the grasses, flowers, and succulent plants that grow with considerable diversity in the longleaf ecosystem. When fire sweeps through the landscape, they may seek cover in a gopher tortoise burrow, or under a fallen tree. They are well equipped to survive in the uplands. For the species to continue, however, newts need to return to those ponds to breed. During the extended dry period, ponds stayed dry and newts disappeared from the Munson Sandhills.

The Coastal Plains Institute has assembled a coalition of partners and volunteers to reintroduce the species to the Munson Sandhills, battling the newt’s biology and global climate trends in an attempt to preserve the biodiversity of the Apalachicola National Forest.

R-Selected Species | Strength in Numbers

Striped newt newly released into an ephemeral wetland in the Apalachicola National Forest. Note the three red stripes running down its back.

Over six years of the repatriation project, CPI has released over one thousand striped newts. A lot of effort went into breeding this large a number, and from a small population at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens. “I find it amazing that the majority of our 1188 newts have been produced by six individuals,” Ryan told us. The good news is that a single breeding pair can spawn several hundred larvae. The bad news?

In the video, you see a spider near where Max deposited two of his newts. The moment each pair of newts left a pair of hands, they entered a world of predators and other dangers. Their primary defense is not a set of ferocious claws or razor sharp teeth- it’s volume. “Amphibians produce a heck of a lot of young,” Ryan said, “It’s called an r-selective reproductive strategy.” I immediately think of how many tadpoles I see in the pond by my house versus how many adult frogs I see afterwards. I also think of the snakes, herons, and large fish I always see moving along the the water’s edge when it is full of tadpoles.

“If you have two parents and you produce a thousand offspring, all you need, really, to produce a stable population through time, is just two of those one thousand individuals to survive.” Of course, there would need to be many more than two survivors for the repatriation to be considered effective. “When we stick one hundred newts into a wetland, say, if only ten of them are observed coming out of the wetland to live out in the uplands, I think that’s success.”

A key word in that last sentence is “observe.” As scientists, Ryan, Rebecca, and friends need to have consistent, quantifiable data to gauge the effectiveness of their efforts. They need to know, roughly, how many newts are surviving, how many newts are returning to the wetland to breed, what wetlands have higher survival rates, etc. This is where striped newt repatriation becomes labor intensive.

The Science Behind Striped Newt Repatriation

If you watched our Roaming the Red Hills series recently, you may remember seeing Pierson Hill standing on an Ochlockonee River sandbar in another part of the Apalachicola National Forest, holding a Florida soft-shell turtle. In the video above, we see him working with a species much less likely to take a bite out of him. Pierson is a biologist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which is partnering with the Coastal Plains Institute to tag the newts.

Florida Fish and Wildlife’s Pierson Hill injects green elastomer into a striped newt. Different color combinations on each newt will help researchers identify them later when they are captured at the drift fence.

After a dip in anesthetic “dream potion,” Pierson injected dyed elastomer implants into four spots on the underside of each newt. It’s a slow process, with most of the newts tagged over seven hours on the day before we released. There are four numbered positions on each newt’s underside. When the newt is belly up, the mark by the front left leg is one, front right is two, back left is three, and back right is four. Each newt is given a unique color combination- for instance, the newt Pierson shows us in the video is Red One, Orange Two, Blue Three, Red Four (or R1 O2 B3 R4). This is each newt’s “name.” Gender, length and weight data is recorded, and the newt is placed in a bucket containing a mixture of its birth water from Jacksonville Zoo and water from its new wetland. This acclimates the newt to the water in its new environment.

This is the first year the Coastal Plains Institute is tagging newts, as it’s the first year they’re releasing sexually mature adults and not larvae. Newts were released in pairs of males and females in the hope that they would get to work creating even more striped newts. If these captive bred newts can successfully breed in the wild, the species is more likely to have a sustainable population in the forest.

Ryan Means inspects a net after running it across the bottom of an ephemeral wetland. Despite catching a few species of frogs, toads, insects, and one turtle, Cobb Middle Schoolers did not find any striped newts.

Each pond is surrounded by a one-foot tall metal enclosure- the drift fence. This lets researchers and volunteers constrain movement into and out of the pond, giving them an idea of how many newts are trying to leave and how many are trying to return. It is critical that the traps are checked at least once a day, as the newts are easy prey when trapped in one of those buckets. Newts caught in the traps inside the fence were trying to get out- their identity is recorded and they are set down on the outside, free to scamper into the uplands. Likewise for those on the outside buckets, returning to the wetland to breed. After three months, no released newts have yet been found in traps. Neither were any newts found when Cobb Middle School students dip netted two of the ponds. As Ryan Means said, “That’s neither good nor bad. It’s just data.”

As it turns out, once a newt settles into the pond, they’re hard to find, even right after release. “Six hours later, Pierson went into that wetland and dip netted very intensively to see how many of the 93 (from the first release) he could find,” Ryan recalls. “The answer was ten.” This was part of a detectability study, which gives them a sense of how they might interpret findings later on.

So far, we see that newts don’t survive in large numbers. They’re hard to find. But the biggest challenge to striped newt repatriation is of a global origin.

Ephemeral Wetlands and Climate Change

Visiting the wetlands where newts have been placed, you’re not going to see one major modification meant to aid repatriation efforts. Each pond has a rubber lining intended to slow draining during dry periods. While we’re seeing full ponds now, recent history and global climate trends are working against the newts having adequate breeding conditions for as long as they need to keep a stable population.

“When these area wetlands normally go dry,” Ryan said, “We wanted a puddle to remain at the center to help out our released striped newts, to help them have two to four weeks longer.”

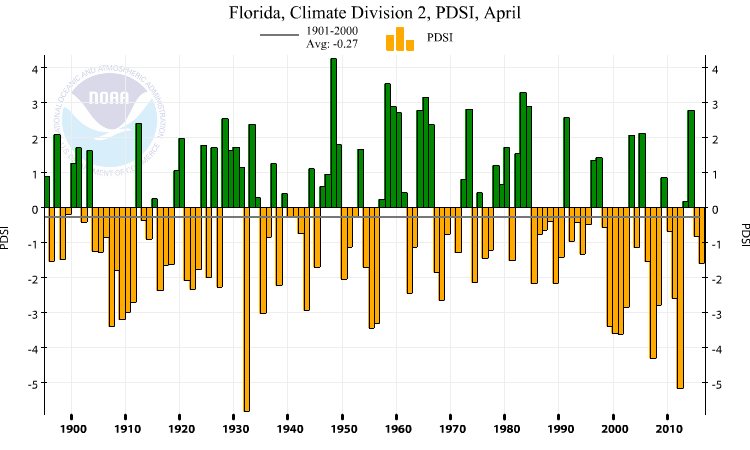

The Palmer Drought Severity Index for NOAA’s Climate Division 2, from 1895 through March of 2016. This region is bordered by the Ochlockonee River on the west, and includes Tallahassee. Data and graph courtesy the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

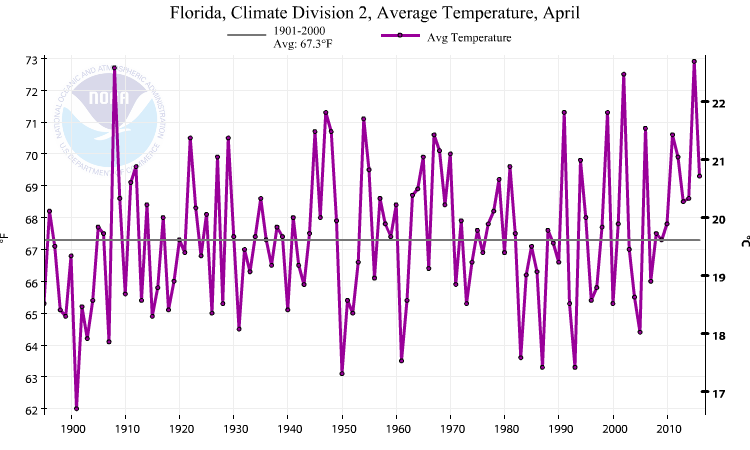

In the video, Ryan references a drought of nearly twenty years that kept wetlands dry for longer than usual. The graph above displays drought severity using the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), which is calculated using rain and temperature, and uses algorithms to account for factors such as evapotranspiration. Evapotranspiration is a loss of water through evaporation and plant transpiration. While we have had rainy stretches during the last thirty years, not all water that falls from the sky ends up in the aquifer. With increasing temperatures, more of that water may turn to steam before it becomes groundwater. The PDSI is not without its controversy, but it is widely used to look at long term drought conditions.

A couple of notes on the graph above. One is that, starting in 1985, there are only eight years not classified as drought years. That’s eight out of thirty two (though 2016 is not complete). Also, four of the five driest years have occurred since 2000. Looking across the graph as a whole, you can see the natural dry and wet cycles- El Niño (wet in the American Southeast) and La Niña (dry) years. These cycles have been affected by increasing temperatures, resulting in harsher droughts and heavier rainfall during wet periods (hard falling rain tends to run off into streams and other low lying areas rather than sink in where it lands).

Average temperatures in our region starting in 1895. Data and graph courtesy the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Striped newts are a local symbol of global climate change. In the coming weeks, we’ll revisit our area’s most famous victim of drought, the Apalachicola oyster. We’ll head out to the bay and get an update on the recovery process, and we’ll also explore the Apalachicola River delta and floodplain, which contribute to the “perfect conditions” in which an oyster can grow. That assumes, of course, that sufficient water is flowing down the river and reaching wetlands in the floodplain forest.

In early 2013, a particularly dry period ended- the second worst drought year since data started being recorded in 1895- and it has been fairly wet since. Within the next year or two, the cycle is likely to flip back to dry. While trends over the last few decades point to favorable conditions for another severe drought, it’s not a certainty. Regardless, Ryan and Rebecca will be monitoring newts in the forest and working to keep them there.

UPDATE: Successful Wild Breeding of Released Newts (May 24, 2016)

Yesterday, The Coastal Plains Institute released the photograph below after Ryan Means and Pierson Hill dip netted this larval newt in a pond where 23 adults were released in January. As Ryan said in an e-mail to partners and supporters of the repatriation effort, “The high-fiving, hootin’, and hollerin’ could be heard across the Munson Sandhills clear on up to south Tallahassee!”

As Ryan mentioned in the video, over one hundred adults were released in January, and over 90 of those into the pond we visited. Taking into account the relatively low detectability of newts in the wetland and the smaller population in the pond where this larva was found, it seems as if this year’s release is off to a good start.

Their dip netting also turned up hope for continued breeding. “We scooped up 2 marked adult males and a marked gravid female yesterday as well, as part of our regular monthly sampling efforts to determine newt detectability.”

Their earlier detectability sampling of that pond, designated Pond 18, gives a general idea of how many newts might be in that pond. “As far as detectability goes,”Ryan said, “yesterday, at pond 18, we dipnetted 3 adults out of a possible 23 released (minus one who transformed and exited)(13.6% detectability). And while doing, we also scooped up the single golden larva. This level of detectability has been rather par for the course, and actually at the high end of what we have thus far, and preliminarily, observed….”

The Coastal Plains Institute is pretty good about posting they daily finds on social media. It’s a good way to track, day by day, how the repatriation is progressing. They also post about the other critters they find, so it offers a pretty good education on the ephemeral wetlands of the Munson Sandhills.

Larval striped newt recovered through dip netting. Note the exterior gills . Photo by Ryan Means, Coastal Plains Institute.

Wildlife in the Munson Sandhills

The Munson Sandhills is located just south of Capital Circle in Tallahassee. After a renovation in recent years, its red clay trails have become well loved by local off road cyclists. It’s also popular with hikers, horseback riders, and wildlife watchers. During our two shoot days spanning winter and spring, we saw a good amount of flora and fauna. Here are the species we see in the video:

00:24 Striped newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus)

03:24 Fishing spider (Dolomedes tenebrosus), a species known to catch small fish and invertebrates in the water.

03:46 Zabulon skipper (Poanes zabulon) butterfly landing on white wildflowers (eastern bluestar?). You see this species and many more in our exploration of the Butterflies of the Red Hills.

04:23 Sandhills milkweed (Asclepias humistrata). Pictured right.

04:23 Sandhills milkweed (Asclepias humistrata). Pictured right.

04:26 Longleaf pine (Pinus palustrus) in grass stage. In this early stage of its life, longleaf stays low to the ground and develops its root system. Grass stage can last into the pine’s teen years. See photo below.

04:52 Red cockaded woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis) at Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. While I didn’t see any on our two trips to the Munson Sandhills, there are plenty of white banded trees containing active cavities.

04:58 Great crested flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus). Seeing something flying by banded trees, I moved closer to see if there was a woodpecker shot to be had. What I saw instead was this flycatcher, bringing an insect to nestlings inside of an artificial woodpecker cavity.

05:07 Longleaf pine. You’ll notice the skinny pines surrounding Ryan Means as he introduces middle school students to a wetland. According to Ryan, these young upland trees encroached upon the edges of the wetland during the aforementioned dry period.

05:19 Oak toad (Anaxyrus quercicus)

05:35 Southern toad (Anaxyrus terrestris)

05:28 Chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia)

05:51 Ornate chorus frog (Pseudacris ornata), one metamorph with a tail and another that had recently lost it.

06:11 Gopher frog (Rana capito), larger and in the foreground, next to an ornate chorus frog. Both are in the process of metamorphosing.

And here’s a neat one the students netted that I didn’t include in the video, a larval dragonfly:

And this giant leopard moth caterpillar, eating a smilax leaf:

A couple of details in the photo below give us a feel for the environment of a red cockaded woodpecker. For one, the longleaf’s black bark is evidence of fairly recent burning. The other is the copious sap dripping down the trunk. The red cockaded woodpecker scores the bark beneath its cavity to release sap and make a difficult climb up for snakes and other potential predators.

And here’s a bird’s eye view of a longleaf pine in grass stage:

The Munson Sandhills is also well known for an abundance of fox squirrels. This region of the forest is located just below the Cody Escarpment, where the Red Hills clay slopes down to a thin layer of sand overlaying the limestone aquifer. Geologically, this region south of the scarp is known as the Woodville Karst Plain, where the aquifer frequently emerges in the form of springs (most famously Wakulla Spring), sinkholes, swallets, and, of course, ephemeral wetlands.

Come adventure with us in the Red Hills, Apalachicola River and Bay, the Forgotten Coast, and More! Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog by Email.

WFSU producer Rob Diaz de Villegas trains new production assistants in the Munson Sandhills of the Apalachicola National Forest.