Video: bird watching, nature writing, and possibly the best sunrise spot on the Forgotten Coast. Author Susan Cerulean joins us at Bald Point State Park.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Susan Cerulean and I are watching a bufflehead duck dive for food by an oyster reef. We’re at Bald Point State Park, and Susan is putting me in tune with nature’s cycles. “You can’t know when that last one’s left,” she says of the duck, which should soon be departing for the north. This is the seasonal cycle, warming and cooling that spurs many of the birds we’re seeing to start continental and intercontinental flights.

We’re here to see as many shorebirds as possible, so we arrive at low tide. Today, that happens to coincide with sunrise. Lunar and solar cycles. In fact, the full moon has exposed quite the sand flat, an epic low tide that we enjoy throughout the morning, as do foraging dunlin and ruddy turnstones. Further off, pelicans and least terns sit at the water’s edge. Through the simple act of scheduling our shoot when we did, I’ve already gotten quite a lesson in the cycles of the natural world.

Bald Point provides a sunrise vista that’s uncommon on our Forgotten Coast. Here, the coast faces straight east into Apalachee Bay, meaning you get to see the sun rise out of the water. While the park doesn’t open until 8 am, there is sunrise beach access along Bald Point Road (Consult this brochure for a map). It’s an hour away from Tallahassee, but I need to come out and start my day here more often.

Bald Point provides a sunrise vista that’s uncommon on our Forgotten Coast. Here, the coast faces straight east into Apalachee Bay, meaning you get to see the sun rise out of the water. While the park doesn’t open until 8 am, there is sunrise beach access along Bald Point Road (Consult this brochure for a map). It’s an hour away from Tallahassee, but I need to come out and start my day here more often.

Once you do get past that gate, you can walk on the beach or up onto observation platforms at the mouth of the Ochlockonee River. Today, the extra-low tide exposes something of an oyster reef maze.

I should have guessed from where I was going that there would be reefs; instead I’m kicking myself for not bringing my “oyster shoes.” That’s my nickname for the old shoes I would save from the trash for my shoots with David Kimbro and Randall Hughes. Many of those took place on the other side of this park in the oyster reefs of Alligator Harbor, where I started following their research for the In the Grass, On the Reef project. Oysters are sharp and are unkind to feet and footwear; it’s best not to bring your favorite pair of shoes. Oyster reefs are a great place to see birds, as they shelter so many invertebrates.

Walking on a reef, if you really look, you’ll see stone crabs, mud crabs, and various predatory snails. Birds love to eat these and the many small fish and shrimp that hide in the crags of submerged oyster clumps. It was no surprise to see, as you may have noted in the video above, fishermen and shrimp boats reaping the bounty of the estuary systems at the mouth of the river.

Oyster reefs also line the edges of Chaires Creek, a couple of miles of winding marshy stream leading to Tucker Lake. I’ve not paddled it, but I have accompanied fishermen retrieving traps full of blue crabs here. There is a boat launch at Tucker Lake, so you can put in kayaks or a boat and maybe go after some of the big fish that forage in intertidal systems. (We ended up kayaking Chaires Creek for a segment in late 2017).

Oyster reefs will cut up your shoes. They can have a strong smell. And the mud around them can be treacherous. I will always love walking on and around them.

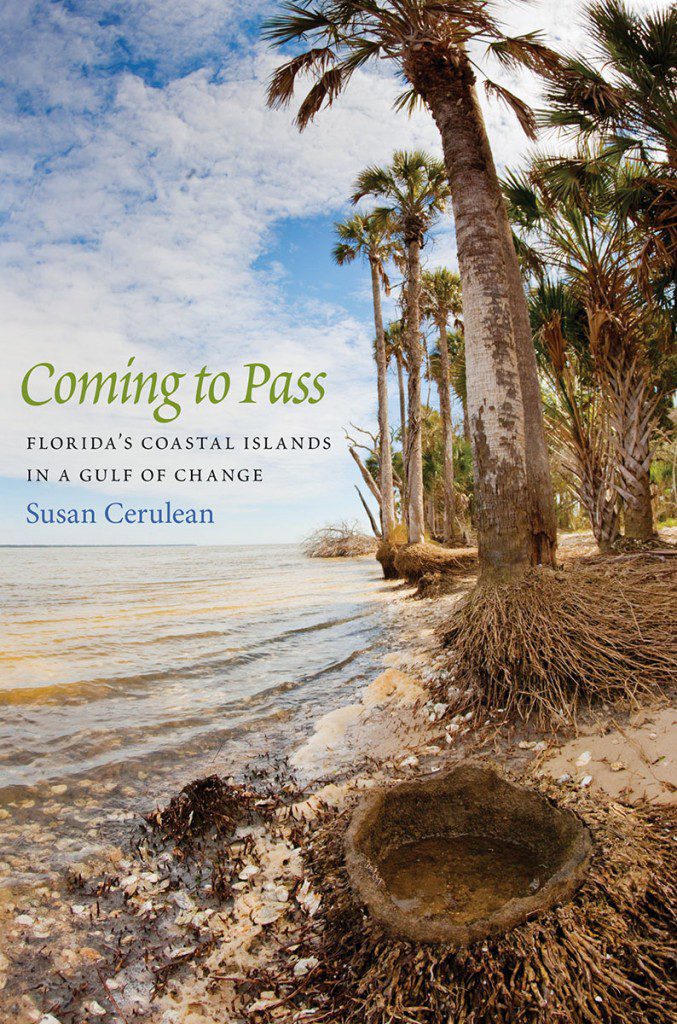

Coming To Pass

Bald Point nicely encapsulates much of what we love about the Forgotten Coast. Susan has spent the last eight years writing a book that captures the very heart of this region; appreciating what we have while we still have it. “Like those buffleheads- you can’t know when the last one’s left,” She says. “And that’s sort of how I feel about our coast.”

Specifically, she’s writing about the barrier islands of the Forgotten Coast: Dog Island, St. George Island, and St. Vincent Island. These islands were created by sediments carried from the Appalachian Mountains via the Apalachicola River. They physically contain the river’s fresh water, creating what had been, until a couple of years ago, one of the nation’s most productive estuaries.

We often think of the peril faced by that estuary as it struggles to receive freshwater in the quantity and with the consistency that it needs. However, the islands themselves are in trouble, being slowly swallowed by the Gulf of Mexico.

Coming to Pass is the result of a journey that started with Susan interviewing her husband, FSU oceanographer Dr. Jeff Chanton. Over eight years, she researched, she visited the people who live and make their living from the coast, she walked from one end of St. Vincent Island to the other. The book is about more than sea level rise. But that is the focus.

In the linked pdf produced by Gulf of Mexico Coastal Training, you can see that it projects to be a slow process. In the 2100 map, St. George looks to lose a little bit of coastline but St. Vincent looks like it’s falling apart. Aside from helping to create the estuary, the islands are a key stop for already diminishing flocks of migratory birds.

Over decades of shorebird counts, Susan has seen big declines in the abundances of each species. “We’re not really set up to see these changes with eyes and senses so much.” She still sees all of the types of birds, but the quantities of each have been shrinking. During those decades, more and more coastline has been developed and habitat lost. Sea level rise threatens to claim more of that habitat.

Luckily, that process is slow. For Susan, it means that we can still do something about it. “I’m grounded in knowing what’s at stake and what’s been lost” Susan says. “But I feel if you only go that far, it’s a dead end. ‘Well, okay then, let’s just have a party.’ But where does that leave the children?” Judging by the passages she read in the video (and the one we didn’t use), this is not a depressing book about our destruction of the planet. It’s as much about the islands themselves, and the bay, and all those things we love. In a way, it feels like a wake up call. Here’s the thing we love; now please don’t let it go away.

Word of South

Susan’s friend, Velma Frye, provided us with two tracks to use in the video. The two of them will be collaborating for a performance piece in the upcoming Word of South Festival that’s hitting Tallahassee’s Cascades Park on April 11 and 12 (it says rain or shine, which is brave for a location that’s designed to flood).

They’re still working on the specifics of combining Susan’s words with Velma’s music, but Velma described it to me like this:

“I’ll begin an instrumental introduction to deepen the response as Sue is still reading and later she will resume reading after I have finished singing the song and am playing a long coda, like wind and water interacting.”

Two of Word of South’s organizers, Mark Mustian and Mandy Stringer, joined Julz Graham on Dimensions this week. Watch the interview to learn more about the festival.

There are Other Nature Blogs on the Internet

Yes, it’s true, this isn’t the only one. I normally try to shelter readers from this fact, but I would like to mention that Susan Cerulean has a blog that she started after completing Coming to Pass. I had been reading it, and throughly enjoying it, when one day I thought to myself “I bet a day with Susan on the coast would make a good video.” I’ll leave that for you to decide; regardless, I enjoyed the process.