At Bald Point State Park, we kayak past a little bit of everything that defines Florida’s Forgotten Coast.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

When we get to the mouth of Chaires Creek, the tide has gone out enough to see the tops of some oysters. It’s a little after 1 pm- high tide was 10:16 am, and low tide is 4:02 pm. If we stay too much longer, the mouth of the creek will be choked by oyster bars, and sand bars will make the kayak back to Tucker Lake slow going.

And then we see some migratory ducks, red breasted mergansers, fishing by the marsh. It’s footage I have to get, and so I end up paddling after them, keeping a cautious distance but close enough to zoom in and see fish in their mouths. It’s part of a pattern today.

The trip from Tucker Lake to Ochlockonee Bay and back is only about three miles. We have several hours in which to do this. The problem is- and it’s my favorite problem- is that it’s such a nice day here in Bald Point State Park. I’m here to get footage, and there are too many things I can’t let the camera ignore.

Often, I find myself looking up from the screen to see three kayaks far ahead. They’re used to this from me. Doug Alderson is the Assistant Chief of Florida’s Office of Greenways and Trails. Georgia Ackerman is the newly anointed Apalachicola Riverkeeper, and had coordinated the Apalachicola RiverTrek paddle trip for years. I’ve paddled a combined hundreds of miles with Doug, Georgia, and Mike Mendez, multiple RiverTrek participant.

Left to Right: Doug Anderson, Georgia Ackerman, and Mike Mendez. I’ve kayaked a combined hundreds of miles with these guys. But then, they’ve kayaked thousands of miles together over the years.

So this is a familiar pattern for them. I slow down, get footage, then hurry up to catch with the group. Over and over again.

When you watch the video, you’ll see why. Mullet are jumping, and I stop to get video of a man casting his net to catch them. I stop to shoot two recreational fishermen, and an oyster boat. It’s late fall (we recorded at the end of November); ducks have recently arrived, and monarchs are still gathering by the water’s edge before heading out over the Gulf.

There’s a lot of great habitat footage to get. I just have to get it before I get stuck.

Planning Your Tucker Lake/ Chaires Creek Kayak Adventure

Before we explore the lively habitats in Bald Point State Park, here’s what you need to plan your own Chaires Creek paddle trip. The first thing you’ll want to figure out is your tidal window- when will the water be high enough to avoid getting snagged by oyster or sand bars?

This link will take you to a tidal gauge at Bald Point. Starting an hour or two before high tide, you can reach Ochlockonee Bay when the water’s at its highest. At this point, oyster reefs should be completely submerged.

Next, what route do you take? We went out to the bay and back, but you have options outside the park as well. This map shared by Visit Wakulla guides you to a ramp by the Highway 98 bridge over Ochlockonee Bay. This 3.7 mile trek keeps you on the Franklin County side of the bay, so you can stay along the coast. There is also a boat ramp across the bay in Mashes Sands, but there is a fee to use it.

This is not a beginner’s paddle, unless you decide to stay in Tucker Lake. Depending on the weather, a bay crossing can be a challenge. Check the winds on Ochlockonee Bay before deciding whether or not to cross.

Finding the Tucker Lake Boat Ramp

It’s an easy turn to miss, because the park sign isn’t right up on the road. Once you turn off of Highway 98 onto Alligator Drive (towards Alligator Point), it’ll be your first left. Once you’ve made the turn, follow the signs to the ramp.

The Florida Circumnavigational Saltwater Paddling Trail

I first met Doug in 2011, on our first EcoAdventure. It was a segment on the FCSPT, a paddling trail encircling all of Florida. Completing the trail is a major undertaking, but the Florida Office of Greenways and Trails has organized it into several dozen segments (link to maps and other resources).

This means you can custom design any number of smaller trips along the coast, choosing your own pace. The key to this flexibility is the spacing of campsites, and here along the Forgotten Coast, there are plenty. The campsite where we had lunch is one of those sites.

So, for the more advanced paddlers among you, your Tucker Lake adventure can continue well beyond Ochlockonee Bay.

Hiking, Bird Watching, and Beach Going at Bald Point State Park

And fishing, too, as we see in the video. The same entrance that takes you to Tucker Lake takes you to the Chaires Creek Bridge, where we see the mullet fisherman casting his net. You can fish from a boat or a kayak, and I’ve seen plenty of people surfcasting from the beach.

The great thing about the beach here is that it’s right next to oyster reefs and salt marshes. Bald Point is at the meeting of two coastlines. One is the north-facing Ochlockonee Bay coast, lined with critical estuary ecosystems. The beach faces east, into the much larger Apalachee Bay. If you squint on a clear day, you can see the St. Marks Lighthouse. And because it faces directly to the east, you can watch the sun rise out of the water.

One of my favorite experiences at this beach was a full moon low tide back in 2015. The beach went on forever that day, as we accompanied author Susan Cerulean as she observed shorebirds and read from her (then) about-to-be-released book, Coming to Pass.

We can see why birders would like the park in the video above (as well as in the segment with Susan). Bald eagles, migratory ducks, shorebirds- and we didn’t even spend much time in the pine woods.

Lastly, there are hiking trails throughout the park. With a variety of habitats and wildlife, the scenery should be anything but monotonous.

Life on Land and in the Water: the Habitats of Bald Point State Park

From the water, you can notice the openness of the pine flatwoods around Chaires Creek. Regular prescribed burns keep hardwood trees from cluttering the view between these pine trees.

Pine Uplands

We start at the Tucker Lake boat ramp. This was once a freshwater lake, but has since been connected to nearby Ochlockonee Bay. The ramp area, and the kayak campsite down the creek, are well above the wetland ecosystems at the edge of the lake and creek. We’re in a familiar kind of pine forest.

Like many of the protected forests we visit, this land was once owned by a paper company. Companies that grew pine for paper, timber, and/ or turpentine once clear cut almost all of the longleaf pine forests that had covered the American southeast. Slash and loblolly pine are similar to longleaf, but faster growing and with lesser quality wood. Much of the pine forest we see today has been replanted with these species.

The trees were planted in rows, as you can see at 01:48, and they were planted much closer together than is natural for this ecosystem. That’s why Kristin Ebersol mentioned that they’re thinning the forest. It seems counter-intuitive that a healthier forest would have less trees. But in a southeastern pine upland forest, the plants that grow on the ground are just as important as the trees.

We don’t spend a lot of upland time in this adventure, but it’s an ecosystem we’ve covered in greater depth with our Roaming the Red Hills series, and in several segments afterwards. These uplands are biodiverse, fire dependent ecosystems.

Salt Marsh and Oyster Reef

Once we’re on the water, marshes are all around us. From some of my favorite vantage points, the grass goes on and on with islands of pine within them. As the tide goes out, we start seeing oysters along the marsh, especially closer to the bay.

Oyster reefs and salt marshes show their health in the very best way: by sheltering lots of things I like to eat. Of course, In the years I spent covering these ecosystems for our In the Grass, On the Reef project, I learned that they do much more than that. They filter water and solidify the shoreline. And they provide shelter to many more animal species than the ones best complimented by a dash of lemon or cocktail sauce.

But, as for a singular image of ecosystem prosperity, how can we do better than this?

This duck’s home waters have frozen over, and it has flown over a thousand miles to find a place to spend the winter. It touches down on the water by Bald Point State Park. And here we see that, cruising between the marsh and some oyster bars, it finds a tasty meal.

Salt marshes, oyster reefs, and seagrass beds are the critical ecosystems of a north Florida estuary. Species like mullet and shrimp find shelter here when they’re young and most vulnerable; on the other hand, predators like blue and stone crabs find habitats full of food.

Miles of protected north Florida shoreline, and the seafood and tourism economies they support, are at the center of the region’s identity: Florida’s Forgotten Coast.

Next to an observation deck just off of Bald Point, the state park has lined the coast with bagged oyster shell. Oysters will settle on such artificial reefs, creating habitat and preventing erosion.

Beach and Sand Dunes

Ducks aren’t the only migrants we see. When I’m interviewing Doug at the kayak campground, little orange butterflies are going crazy behind him. We made this trip in late November, at the tail end of the monarch butterfly migration season.

Monarch butterflies “hug wings” on pine needles just behind sand dunes at Bald Point. On our beach shoot day, monarchs continuously flew over dunes, sometimes departing over the water.

Regularly burned pine woods are full of flowering plants, as are protected sand dunes. Here, monarchs can fuel up before their long flight across the Gulf of Mexico to their wintering grounds on the Yucatan peninsula.

The dunes are also an important nesting habitat for shorebird species. You can see several species foraging along the beach at Bald Point- at this time of year it’s a mix of resident and migratory birds.

In our segment with Susan Cerulean, she talks about walking with caution around shorebirds during there nesting season. This will start as winter transitions to spring. When we walk to close to their nests, we scare them off and leave their eggs vulnerable to ghost crabs and other predators. When they become threatened and fly away and back, they use precious energy (parents of newborns can relate- you need to conserve your energy!).

The Ochlockonee River Watershed

A couple of months ago, we visited the Bradwell Bay Wilderness with Dr. Bruce Means. As I mention in that post, that swamp provides nutrients to oysters and other critters at the bottom of the Ochlockonee Bay food web. So, while it’s important to have healthy marshes and oysters, the health of the estuary depends on a much larger system, one that covers over a hundred miles of river and wetland habitat.

The Ochlockonee River is an interesting case. It starts south of Macon, Georgia, and receives pollutants from its tributary streams. Additionally, its water level is affected by cotton farming. Cotton is a thirsty crop, and when we kayaked the Georgia part of the river in 2015, the water was much lower than other local rivers I had kayaked at around the same time.

As I mention in the post I just linked, a lot of that pollution doesn’t make it past Lake Talquin, just outside of Tallahassee. This lake is created by the Jackson Bluff Dam, and the water that flows from the dam and into the Apalachicola National Forest is cleaner than what flows in from Georgia.

In 2015, we got a good look at the Ochlockonee just south of the dam. Children had gathered for a Bio-Blitz event held by Tall Timbers. If you’re not familiar with what a Bio-Blitz is, during one you catch (and release) and/ or count as many animals as you can within an hour or two.

The Florida softshell turtle (Apalone ferox). It lacks the protection of a hard carapace, but as FWC biologist Pierson Hill says “what they lack in armor, they make up for with jaws and claws.”

If you have time, you can check out the linked videos and get a sense of this large river system. Of course, these are just snapshots. There are just so many more things for us to see…

Let’s Appreciate the Relative Warmth of Florida

We’ve had a colder than usual winter in our area, which included snow that didn’t immediately melt when it hit the ground. So, since we’re talking about salt marshes today, I thought it would be fun to share some photos from my Christmas vacation in Duxbury, Massachusetts. The photos below were taken within a month of our Chaires Creek adventure.

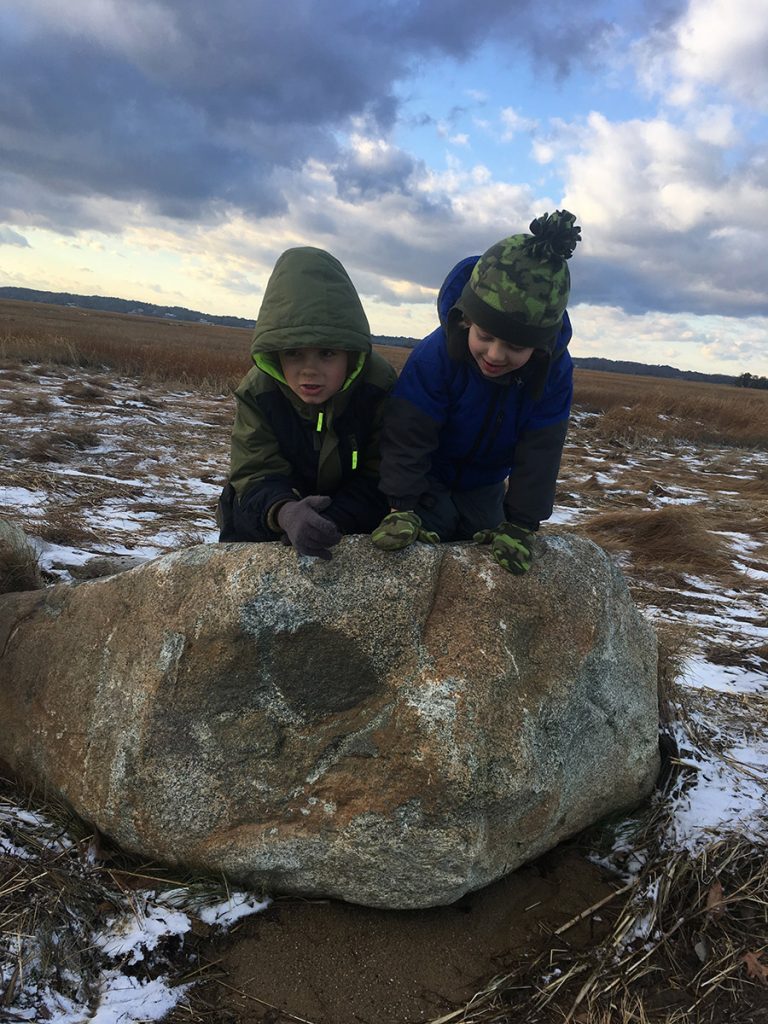

My sons and I took the opportunity to explore the frozen salt marshes by their Grammy’s (my mother in law) house. We left at the same time, more or less, every morning. But with the tides shifting by about an hour a day, we got to see the marshes at different water levels every day.

For the first part of our vacation, it got above freezing by mid-day, enough to melt and re-freeze the ice sheets above. So every day, the ice was a little different.

The ice and snow seemed to kill back some of the marsh. I imagine this has a similar effect to seagrass wrack killing off marsh in our area. Our former collaborator, Dr. Randall Hughes, studied this. When piles of wrack land on marsh grass (Spartina alterniflora) and kills it, it opens up space for other plants, increasing species diversity. Also, a single genetic marsh grass individual can spread out pretty far, connected underground by rhizomes. So newly open spaces let new genetic individuals in, increasing genetic diversity.

Perhaps ice and snow have a similar effect?

There were also a lot of dead crabs and snails.

I enjoyed exploring the marsh with Max and Xavi. We were lucky to be able to go over several days. We saw the tide at different stages, and covered in different of amounts of ice, and eventually, snow. I get this idea in my head that it’s an educational experience for them, that they’ll learn about estuary ecology. But right now, at ages 4 and 6 (soon to be 7), the experience is the thing. They tested the edge of frozen puddles with their feet, and witnessed a snow storm cover a marsh (I didn’t even see snow until I was 25). They’re building connections to natural areas; we’re building them together as a family.

Anyhow, stay warm north Florida!