The name Red Hills is perhaps underused by those of us who actually live here. That’s why the folks at Tall Timbers set out to reintroduce us to the area between the Ochlockonee and Aucilla Rivers, from Thomasville to Tallahassee to Monticello. In defining this eco-region and the benefits we receive from living here, I gained a new perspective on our longer running exploration of the Forgotten Coast and its own gifts and uniqueness. I’ve often written about miles of unspoiled coastline and how that benefits our seafood industry. But any large healthy tree has an equally large root system that we don’t see, and for our estuaries these are miles of unspoiled river banks, sloughs, springs, and lakes. In our last EcoAdventure we hiked along sloughs in the backlands of the Apalachicola River floodplain, little fingers reaching into the nutrient rich muck to send it on its way to the bay. In the video above, we visit the lakes of north Leon County, through which water enters the Floridan Aquifer. This is our water, the water I’m drinking as I write this. It’s the water that feeds our springs, such as those that in turn feed the Wacissa River. That water emerges from Wakulla Springs, which flows into the Wakulla River and down to Apalachee Bay.

This adventure was about more than just the lakes, which were great to kayak and SUP. These lakes are protected by forested land that filters storm water runoff and buffers them from pollution. That’s an ecosystem service the land provides. That’s a value that we receive, as consumers of the water. We also receive the benefit of having the land to visit as parkland or, for the hunters who own private forested lands north of Tallahassee, to hunt animals sheltered in the habitat.

There is often this tension between ecology and economy, a perception that land has more value if it can be sold as real estate or built upon with stores and offices. That’s why there has been a push in recent years to put a dollar amount on ecosystem services. In our collaboration with Randall Hughes and David Kimbro, we’ve cited a study that determined the value of a salt marsh. Tall Timbers has been promoting a similar study conducted at the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forestry an Natural Resources on the services provided by the Red Hills. For a detailed look at how Dr. Rebecca Moore determined the value of services, click here.

The total value of Red Hills ecosystem services determined by the study are $1.136 billion per year. We focus on groundwater recharge ($229 million) and water supply protection ($615 million) in the video. Another service is pollination, at a value of $60 million. That means that the forested land around town supports pollinating species like bees and butterflies to the advantage of both farmers and us amateur gardeners. Aesthetic value is listed as $163 million.

The one thing that has surprised me the most since I started talking to Tall Timbers about this piece is that much of the forested land providing these services is privately owned. Tall Timbers estimates that there are 445,000 acres of forested land in the greater Red Hills Region. Over 300,000 acres are privately held on largely contiguous quail hunting properties. Many of these properties were purchased in the 1800s and early 1900s, sparing them from logging and preserving old growth coastal plain forest. These forests, and the bobwhite quail that live there, are what drew people here.

The Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy

One of the people drawn to the Red Hills was Henry L. Beadle. His hunting plantation on Lake Iamonia is where, in 1958, Tall Timbers was established. It was his desire to have a place to conduct research on fire ecology and its effect on “quail, turkey and other wildlife, as well as on vegetation of value as cover and food for wildlife.” While hunters in the area had made use of fire to manage the longleaf/ wiregrass ecosystems on their property, it wasn’t until fairly recently that it became a mainstream practice (get two land managers together and see if they don’t start trading fire stories). Tall Timbers mission is to “foster exemplary land stewardship” while also “respecting the rights and recognizing the responsibilities of private property ownership.” They are advocates of “smart growth,” development with a broader view of economic feasibility. That means factoring in the value of ecosystem services when planning new development.

Lake Iamonia

It seemed like the appropriate place to begin the adventure. It’s Leon County’s largest natural lake, and it has an interesting hydrology. Michael Hill from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission met us on the lake to talk about the work he and FWC have done to restore the lake. I met Michael for the first time last fall on Lake Lafayette. Like Lakes Iamonia, Jackson, and Miccosukee, Lake Lafayette has a sinkhole that connects to the Floridan Aquifer. All of these lakes had natural dry down cycles, where the lake would cyclically empty and refill. In the early twentieth century, people viewed this draining as an ecological catastrophe. They set out to “save the lakes.” They built earthen dams to isolate the sinkholes from their lakes. This kept the lakes full, but disrupted much of their ecology. On Lake Lafayette, Michael showed us the effects of a lake not being able to go through its normal drought/ rain cycles. Muck builds up on the bottoms of these lakes, and floating islands of vegetation called tussocks form. This alters the habitat for fish and other species. And removing tussocks is an expensive process involving herbicides and heavy machinery.

Water flows under the twin bridges on Meridian Road, from the Ochlockonee River into Lake Iamonia. February 27, 2013. Photo by Michael Hill, FWC.

Lake Iamonia’s dam failed, however, and the gates were removed. This allowed the lake to dry down again, and for FWC to come in and scrape the muck off of the bottom. “We’d seen that there were two to four feet of Muck,” Michael told a gathered group of Tall Timbers employees. “Muck is aquatic plants. It’s at advanced stages of decomposition.” When the lake dries down naturally, the sun dries the bottom. When it doesn’t, muck accumulates. Seeds start growing in it, and it starts to float on the surface of the water as islands. The fish that spawn on the lake bottom prefer a sandier surface, so muck inhibits them. During Iamonia’s last dry down, FWC removed 23 acres of muck. Last year, they removed 25 more. But just as the lake was full for 40 years, Michael thinks it might take another 40 or 50 more for the muck to completely disappear.

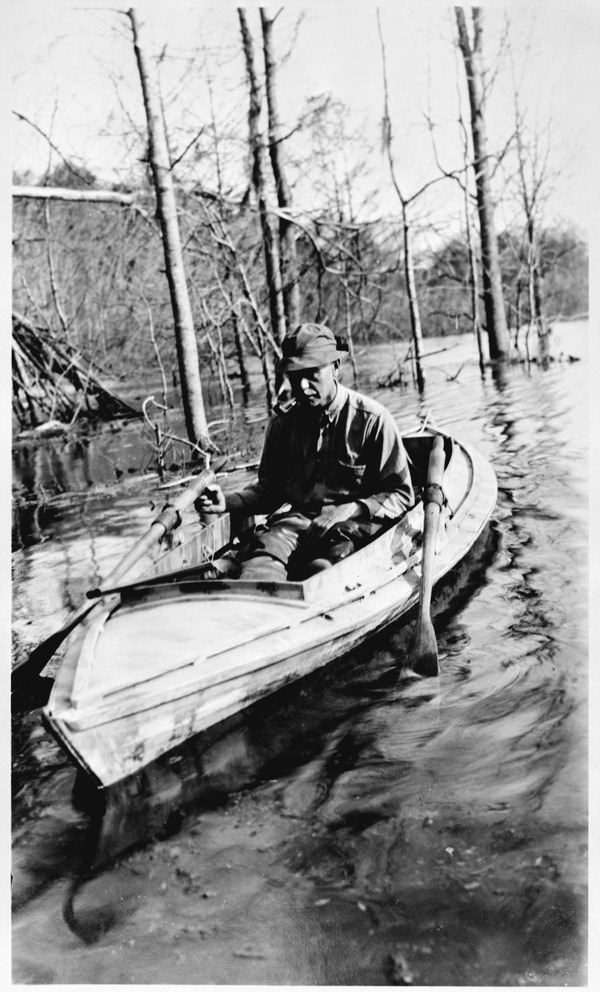

The other interesting feature of the lake is its relationship with the Ochlockonee River. While the river does not flow directly into Lake Iamonia, it does feed the lake by overflowing into it. Michael shared some photos of this flooding, which mainly passes under Meridian Road at the twin bridges that run alongside the lake. Iamonia dries down every seven years, and it is filled by rain and by the flooding Ochlockonee.

Elinor Klapp-Phipps Park

After we left Michael, we went not to Leon County’s other major lake, but to land adjacent to it. It was a cooperative purchase between the City of Tallahassee and the Northwest Florida Water Management District (NFWMD). “Their interest was the activity centers; the ball fields and the soccer complex,” Said NFWMD’s Tyler Macmillan. “Our interest was a passive recreation area that protected Lake Jackson.” Hiking through when we did, during the rainy season, we saw a variety of water features at Klapp-Phipps Park. The were small creeks and swamps as well as places where stormwater runoff ran alongside or directly on the path. One number I found interesting in the Ecosystem services report was the value of urban/ suburban forested wetlands. Rural forested wetlands are valued around $4,600 an acre annually; those in urban/ suburban areas are valued at $8,200. The reason for the disparity is that urban wetlands are less common and, in a sense, work harder to abate pollution and filter runoff.

For Tallahasseeans who like to hit park trails, these are great. There are miles of trails in this network; it’s not hard to get lost. After years of walking greenways and trails in Tallahassee parks (we have quite a few), I’m surprised it took me so long to find this one.

Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park

After lugging me around Lake Iamonia in a tandem kayak, taking my son Max out on a paddleboard must have been a breeze for Georgia.

When I think of this park, I think of flowers. And pollen. Years ago when I produced WFSU’s music show, outloud, we brought local zheng player Haiqiong Deng to the gardens to record a few pieces. Spring had just sprung, and after every piece we stopped to wipe a layer of yellow dust off of her instrument and our gear. The combination of music and setting made it one of my favorite episodes of the show, which ran for almost ten years.

The park has much more than these gardens, with miles of trails and Lake Hall, which I managed to not fall into while learning to stand up paddleboard (I do come close, as you can see). It’s a place where you can take your kayak, canoe, SUP, or sailboat and not worry about motorboats. Lake Hall is considered to have some of the best water quality in Leon County. Park manager Elizabeth Weidner told us that in recent years they have installed collection ponds adjacent to the roadways around the park to collect stormwater runoff.

I had a great time exploring these places, and gaining a larger perspective on how water moves through a watershed and beneath us in the aquifer. We’ll be further expanding upon this theme while we continue to look for great places to spend a day (or more). I don’t like to jinx myself by saying what we’ll be shooting in the coming weeks, as the weather can be uncooperative (we got the video above on our third try). Let’s just say we’ve planned a hike in a place with a reputation for being difficult and are heading back to the Apalachicola basin for a seasonal treat.

Follow us on Twitter @wfsuIGOR