During our second full month of working and schooling from home, I was again able to see plenty of backyard wildlife. The beginning of May picked up where April left off, with plenty of butterfly activity. As the month wore on, we started seeing plenty of different bees as well. And we’re starting to get caterpillars!

I’m not just looking for pollinators, though they are attractive and so helpful. It’s all of those leafhoppers and soldier flies and hard to identify insects that intrigue me. Even in our small yard, which is largely paved, we see a high diversity of insects. All we have to do is look, and make an effort to find out what we’re seeing.

But let’s start with those butterflies. Once again, the lantana bed attracted a diverse lot to the yard.

Pollinators Part 1 | Butterflies

Spicebush swallowtail (Papilio troilus)

This is a returnee from last month. I like this photo better, though. Here we see the underwing of the butterfly, where last month we saw the overwing.

American lady (Vanessa virginiensis)

I originally thought that the butterfly on the right was a painted lady. Both species have similar patterning, and in my butterfly guide, the painted lady had that same orange hue. Also, look at the stripe close to the tip of the of the wing of the two butterflies above; one is orange, one is white. Painted ladies have this white stripe, and that lighter orange coloring. But the rest of the pattern is off from a painted lady’s.

This is the danger with a compact field guide- you only get one photo of an adult. I did a Google image search and found that American ladies have some variation in their coloring, which we’re seeing here. I like that I’m seeing more than one, because I let their host plant grow all over the yard. Cud weeds are not really attractive plants, but they do host American ladies. I never did see their caterpillars in the yard, though.

Here’s a photo of the underwing. Look at that pattern. These Carolina cherry laurel trees are on the side of our house opposite the lantana. They attract a few butterflies, but as we’ll see in a little bit, their flowers are a big hit with bees and wasps.

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

While we’re on the laurel cherries, here’s a common visitor to our yard. I think I saw this one for two or three days, early in the month, crossing between these trees and the lantana. A few times I saw this crossing, which took it over our milkweed plants. I think it was waiting around its host plant for a mate.

Eventually, I did see one egg on a plant, and then some nibbled leaves. That leaf grazing stopped fairly soon, though. It seems to have been a small batch, perhaps one or two. Monarchs usually beat the odds by laying many more eggs than that. We still hadn’t regrown all of our leaves at this point. Writing this in early June, our plants are ready for a large wave of caterpillars to descend on them.

After receiving many unseasonable winter monarchs, even after we cut back our milkweed, things had tapered off by early May. I haven’t seen another monarch in weeks. I expect when I do, it’ll be the migratory population, and our milkweed will be continuously eaten.

Common buckeye (Junonia coenia)

Here is a butterfly that hosts on fog fruit, which I have planted in the yard. I saw some nibbles on these plants in March, but could never find a caterpillar. And buckeye caterpillars would become conspicuous after a while, and would have eaten much more than what I saw. They also host on plantains, toadflax, and false foxglove. So it may not have hosted in our yard, but it would be cool if it was coming to lay eggs. I haven’t seen any new signs of grazing, though.

Horace’s duskywing (Erynnis horatius)

Here is another butterfly we saw last month, and that is one of our more regular visitors. The wings looked more ornate than the other Horace’s duskywings we’d been seeing. Doing some Googling, I found out that this is the female.

Tropical checkered-skipper (Pyrgus oileus)

And here’s another common visitor. I love how beat up its wings are. It’s amazing how much damage their wings can sustain and still fly.

I saw a different checkered-skipper deep in a thicket of fanpetals. This is, as I’ve written a few times, their host plant. And here this butterfly is, curling its abdomen as if to lay eggs. This is the second time I’ve seen this happen in the yard. I’ve seen nibbled fanpetal leaves, and these butterflies are regular residents in the yard. But I’ve never seen eggs or caterpillars. I need to look more closely, and possibly more at night.

Long-tailed skipper (Urbanus proteus)

There were a couple of butterfly caterpillars we saw this month, and both are regulars in our yard. Early in the month, I saw this long-tailed skipper. Then I saw two, and then three. Our bean plants had sprouted and were getting bigger. I kept looking under leaves, and looking for the tell tale sign of their caterpillar, which I finally saw:

Long-tailed skipper butterflies are known as bean rollers, and this is why. I then looked under other leaves, and found some eggs:

They tend to feed at night. But even if you never see them, you can measure their growth by the size of the leaf folds. I haven’t been looking at our plants at night a lot lately, so I hadn’t seen the caterpillars. And then, one day, a huge one was sitting out in broad daylight:

This one is big, with pronounced yellow stripes and a red head. Soon, it would make its chrysalis in the leaf litter I let sit around the plant. They may also pupate in dead leaves hanging from the plant itself. I found one of these a couple of years ago. So I let dead leaves sit on bean plants, and fallen leaves sit around them.

People consider these guys garden pests, and this year, I felt that. We’ve had a dry couple of months, and as much as I tried to keep the plants hydrated, they’ve not grown very large. And maybe we had a few more caterpillars than usual. They really tore up the plants this time around.

Anyhow, that large caterpillar noticed me photographing it right away, and retreated into its large leaf roll:

Giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes)

I was in the backyard one day when I saw this happen:

This giant swallowtail never really stopped flapping its wings. I noticed the same thing filming one at the Lake Cherokee Pollinator Garden in Thomasville. If it deposited eggs on this Meyer lemon tree (they host on citrus), it did so quickly.

I couldn’t find eggs, no matter how much I looked. A few days later, though, I found this:

Did momma giant swallowtail lay her egg or eggs on this cluster of new leaf growth? Caterpillars of other species often hide in new flower growth or where new leaves sprout, where they’re less out in the open compared to on a larger leaf. And I’ve read that new leaves are easier to eat than older, tougher leaves.

Here is a later instar of that caterpillar. I’ve only seen one on this plant. It’s gotten shinier, more like bird poop. The brown and white patterning is an effective camouflage on lichen covered branches.

Silver-spotted skipper (Epargyreus clarus)

Another returnee from last month. Last month it was in the shade, so I like this photo better.

Zebra longwing butterfly (Heliconius charithonia)

I saved this butterfly for last because of the flower it’s on. We’ll see much more of the winged loosestryfe in the next couple of sections. When the lantana bloomed in full, we started seeing a lot of butterflies. When the laurel cherries bloomed, I started seeing more and more bees and wasps, but higher up. Now the loosestryfe, coneflowers and coreopsis are blooming, and I’m seeing more bees and wasps at eye level.

I’ve seen zebra longwings on this plant before, and until this bloomed, I’d only seen them fly over our yard without stopping. I’ll see much more of them when our cardinal guard blooms later in the summer.

The plants in our yard set the schedule for when we see each species of insect. This is part of why it’s important to plant native wildflowers. Our native pollinators evolved with these plants, and their schedule for breeding, larval feeding, and emerging as adults is tied to the availability of food. Likewise, those plants bloom when pollinators are flying because they need that help in reproducing.

Right now, a bunch of new blooms have brought a bunch of bees into our yard.

Pollinators Part 2 | Bees

These trees are right outside of where I’m writing this, and where I edit video. One day, I started seeing shapes move across my window. Too small and slow to be birds, and bobbing like insects. I went outside and noticed these flowers, and, over time, an increasing level of activity around them. One day I saw a carpenter bee fly up to the flowers, and on another I saw a bumblebee. Soon I saw a lot of activity up there, though the camera could only catch the larger insects. Here’s a honeybee (which, again, not native), which we’ve seen more of in the yard this year.

How had I never noticed the pollinators on these flowers before 2020? One reason is that they’re busiest during work hours, and now I’m home to see them. Anyhow, it seemed as though there were plenty of small bees up high, but I couldn’t make them out. Luckily, when they did start finding flowers closer to me, I had plenty of time to photograph them.

Halictidae | Sweat Bees

I’ve been photographing and using iNaturalist to identify small sweat bees for a couple of years now. Next to honeybees, these are the most numerous bees in the world. Many of them are also extremely difficult to differentiate from each other. I’ve done a bit of reading and researching about them this year to help me better understand what’s what. I realize now that I may have mis-identified some species in the past, and I’ll be going through the blog and fixing the one or two instances where I’ve done this.

I also understand that there are some of these bees for which I’m only going to be able to identify a genus or subgenus. As I’ve been writing this, I’ve spent some time mapping out the tribes and genera of the sweat bees I’ve been seeing, and researching the individual bees. I’ll keep my findings simple when presenting them.

Subgenus Dialictus

These bees are the most problematic to identify. They’re in the genus Lagioglossum, subgenus Dialictus. This subgenus contains hundreds of bees worldwide, and they’re almost impossible to distinguish from one another. One problem, as noted on the Bugguide page on Dialictus, is that they’re too small to photograph in great detail. The page also notes that it can even be difficult with a microscope.

I likely have at least two species of Dialictus, based on size alone. Here are two smaller and one slightly larger:

On winged loosestryfe.

Fanpetal flower.

Red salvia.

I went out and measured these flowers. Loosestryfe is about a centimeter across. Fanpetals about 1.5 cm. The part of the filaments sticking out past the petals on red salvia are about .9 cm. The two on the left seem to be less than half a centimeter long. The one on salvia looks a little larger; this image is clearer after cropping, where the other two were cropped maybe a little too far in.

This is one of the larger Dialictus. Leavenworth’s tickseed flowers measure between 2.5 and 3 cm from petal to petal. If you have small black insects pollinating your flowers, take a closer look. These native bees are easily missed, but you might have a lot of these buzzing around with your more conspicuous bee visitors.

Ant Ambush!

Before moving on to the next sweat bee, take a look at what happened to this Dialictus.

I’d been noticing these large ants on the Leavenworth’s tickseed. Were they pollinating the plant?

It’s not the best photo, but you can see what happened here. But don’t worry, the bee escaped a moment later.

Poey’s Furrow Bee (Halictus poeyi)

This is a bee I had been confusing with the Dialictus bees, but I’ve finally figured it out. Sweat bees in our yard fall under two different tribes. Lagioglossum (and subgenus Dialictus) are in the Halictini tribe. So are Poey’s furrow bees, and a bee we saw tons of last August, the brown winged striped sweat bee. Each belongs to a different genus.

This is one of the clearest and most detailed photos I’ve taken of this insect. A couple of things stand out. It’s a little larger than the largest Dialictus. It has a striped abdomen. This was more subtle in other photos I’d taken. And it has a wider head proportionate to its body.

I like how the furrow bee immerses itself in this lance-leaved coreopsis, a larger flowered relative of the tickseeds shown above. We had two or three Poey’s at a time in our yard, hopping between the two Coreopsis species.

Last year, they liked the cut-leaf coneflowers, which are also yellow, but those aren’t blooming this year.

Pure Green Sweat Bee (Augochlora pura) | Tribe Augochlorini

Here’s one of my favorites, along with the brown winged striped sweat bee, which we haven’t seen yet (again, they were swarming the yard last August). I’ve never had an iNaturalist user confirm my ID of this bee, but I had two finalists when using the compare feature on the app.

This is a smallish bee, but you can scroll up to see how much bigger it is than Dialictus on the same flower.

Last year, I identified this as a pure green metallic sweat bee on iNaturalist. This year, I saw an option for an almost identical looking Augochlorine called a metallic epaulleted sweat bee. Since I was unable to see any difference, I decided to look at behavior; specifically, their nesting behavior.

Pure green sweat bees are known for nesting in rotting wood. Last year, I first saw these blue bees when I removed an old wooden bench from the yard, and two of them flew out of it. They also nest in the ground; after I disturbed them, they then seemed to start looking for a spot under our laurel oak. Since I see these blue/ green bees every year, I feel fairly certain that the one in the photo is the same species I’ve been seeing.

I found a research paper on the nesting habits of the metallic epaulleted sweat bee. The paper starts by stating that this species’ nesting habits had never been studied before. They only studied one nest, a ground nest. Nowhere does it say they nest in rotting wood, but we know that pure green sweat bees do. So, for now, that’s my ID.

Carpenter-mimic leafcutter bee (Megachile xylocopoides)

Here’s a bee I’d never seen before. I was by the flower patch when I started seeing a blue blur zipping around the flowers. It stopped on loosestryfe briefly, and I saw it was fuzzy like a bumblebee. But loosestryfe has small flowers, and bees tend to grab what they want quickly and move on to the next flower. When it stopped again, I noticed its smooth abdomen, more like a carpenter bee’s.

That abdomen is where it gets part of its name. And the bluish tinge of the wings explains the blue blur I see when it flies. And look at those mandibles.

When I see missing chunks of leaves, my instinct is to look for caterpillars. But these bees slice leaves, and take the fragments to line their nests.

This is a aggressive bee species. Red-marked pachodynerus wasps have been nesting in the yard, and we see two or three gathering nectar in the flower bed. The leafcutter bee is always flying up and chasing them off of flowers, only resting once the wasps have left. It seems a little more tolerant of other bees, but it’s always keeping an eye on pollinators in this bed.

Here’s one last photo. By late May, early June, we’ve had several coneflowers bloom. These larger flowers keep pollinators on them longer than the tiny loosestryfe, which, as a photographer, I like.

Two-spotted long-horned bee (Melissodes bimaculatus)

This is another returnee from last year, though I’ve had more chance to see it this year. I haven’t been able to find much information on it, other than males clasp onto the undersides of leaves and hang upside down, sometimes in groups. I’ll have to look for that.

This is one of the bees that will hang on flowers, like bumblebees or carpenter bees. These are the bees I see on pentas and sage, that are large enough to hold onto the flower while gathering their pollen. The sage is also popular with the smallest of the bees, that can rest on the filaments or climb inside the petals.

Eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens)

I’m always happy to see bumblebees in the yard. Every few days, one would show up and work its way through several flowers before departing. Many of our other bees seem to stick to specific flowers, or a couple, and can be seem on them daily. Bumblebees hit every part of the buffet and take off.

Even though we seem to have a carpenter bee nest or two, we only rarely see them on our flowers. And even more rarely when I’m holding a camera.

Pollinators Part 3 | Wasps

Great golden digger wasp (Sphex ichneumoneus)

Here’s a wasp that I haven’t seen on any of our eye level flowers. But it is large enough for me to see it up in the cherry laurel flowers.

Red-marked pachodynerus wasp (Pachodynerus erynnis)

This has been a common wasp in our yard, with multiple nests here in the bee house. As I mentioned earlier, they make use of our main flower bed and various other flowers.

Last month, I noticed a much higher diversity of wasps in the yard. Are there less of them this month, now that more bees are on the flowers? Or are they more interested in the higher up flowers, where I’m less likely to see them? Every month, we see different blooms and different insects on them. I know in August, when the dotted horsemint blooms, that we’ll see more solitary wasps.

Pollinators Part 4 | Moths

Once again, I noticed a few different moths in the yard. They’re not so much active during the day, but we can catch them at rest in various spots in the yard, or flushed out when I’m watering plants.

Frilly grass tubeworm moth (Acrolophus mycetophagus)

This was resting on our fence one afternoon.

White satin moth (Leucoma salicis)

I believe this is a white satin moth, which is a species introduced from Europe in the 1920s. It was inside our house.

Edit January 8, 2021: An iNaturalist user suggested the subtribe Spilosomina, which is a tiger moth. There are tiger moths that match the look of this moth. When I looked at the range map of the white satin moth, all of the North American observations were far north of Florida. I’ve been relying more on the map, though sometimes species move out of their range, whether their range is affected by a warming climate or humans introduce a species, intentionally or not. We want to be cautious recording anything out of the ordinary, as exciting as it would be to be to witness something new. But if you do indeed observe a plant or animal outside of its recognized range, an iNaturalist observation adds the new location to research databases.

Wedgling moth (Galgula partita)

I thought this was an interesting looking caterpillar roaming in the leaves around our milkweed plants. Moth caterpillars can be challenging to ID in iNaturalist. The autorecognition AI suggested owlet moths and allies. I clicked compare, and waded through a couple dozen owlet species spotted in our area, when I saw a photo of a similar looking caterpillar. It looked so different than the other owlet cats, I wondered why wedgeling moth wasn’t the top option.

It hosts on Oxalis species, of which we have two growing in the yard.

Citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella)

These little trails on leaves are made by small moth caterpillars. I keep seeing tiny little moths flickering about the yard; I think it might be these guys.

Flies

Soldier flies

Last month I photographed a black soldier fly, whose larvae help break down compost. This is another type of soldier fly, with perhaps similar larval habits. I couldn’t find any specific information, though many soldier flies do eat decomposing organic matter.

Xanthaciura, a genus of fruit flies.

I’ve seen one or two of these in the yard, and perhaps they’re associated with our compost as well. Here it is on a lance-leaved coreopsis bud, and I’d previously seen it on a Leavenworth’s tickseed bud. Maybe it’s just that these make nice perches?

Leafhoppers and planthoppers

These are garden pests, and some species can spread pathogens between plants. But the ones I’ve seen this month are interesting looking, anyway. I don’t see any one species in any great numbers, and the plants seem healthy. My attitude towards these and other pests is that, in small or moderate numbers, they’re part of the biodiversity of our yard. I need plenty of insects to feed the birds and skinks and anoles I see, and the tree frogs I hear.

Northern flatid planthopper (Flatormenis proxima)

This one has a pleasant monochromatic appearance, very clean looking. And I seem to have found one of its nymphs (immature form), which is also cool looking:

Glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis)

This is a large leafhopper, much different in appearance than the ones I’ve photographed before.

Other insects in the yard

Cactus Lady Beetle (Chilocorus cacti)

Last month, I was lamenting that the only ladybugs in my garden were invasive Asian lady beetles. So I was happy to see this native ladybug, a twice-stabbed lady bug. There are a couple of species that get called twice-stabbed; the larger red spots led to this ID.

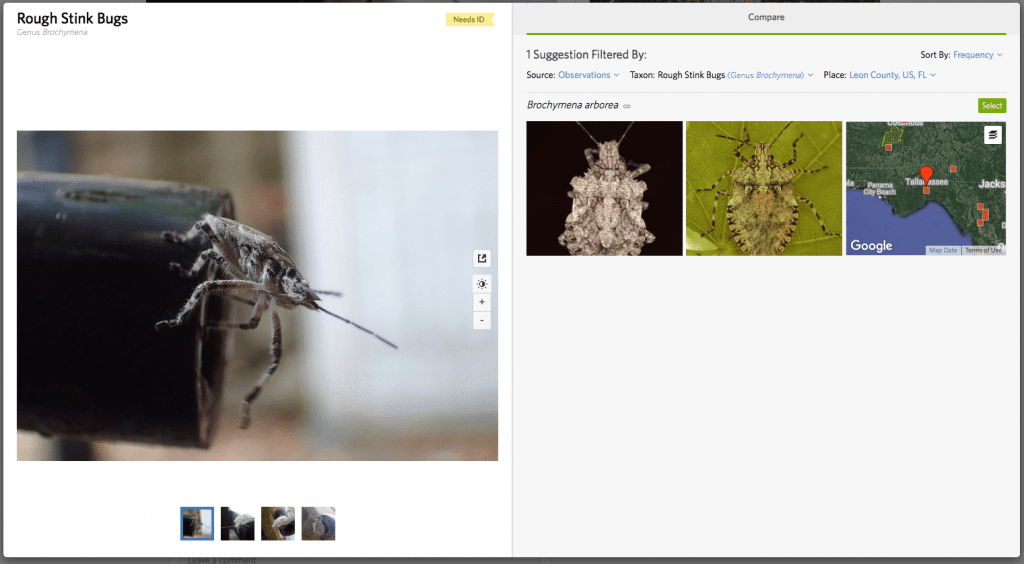

Rough stink bug (genus Brochymena)

This one has me baffled. I looked through several stinkbug and shieldbug species on iNaturalist and I don’t have anything close to a certain ID. Another user suggested rough stinkbugs, and it at least looks like it belongs to this group.

I ran several combinations of filters using the compare feature in iNaturalist. It defaults to showing you any observations of your guess’s species or genus in the county where you observed them. But some animals are either uncommon or not often observed, so you can remove the location filter or expand it to state or country, which I did here. You can also expand from species or genus to a tribe or a family (like all stinkbugs), or even a superfamily (stink bugs, shield bugs, and allies). I ended up browsing through every species of stink and shield bug observed in the US, and nothing seemed to fit quite right.

Sometimes it happens that way. Maybe this is a subspecies, or part of a species with a varied look. To me, that’s part of the fun of learning about plants and animals. They don’t always fit in tidy boxes regarding the way they look and act. And working with researchers, and covering their discoveries, you get a feel for how our knowledge of the natural world is always evolving.

Is it frustrating when you can’t pin down an identification? Sure. But why not embrace that you’ll always have something new to learn about nature?

Stinkbug observed May 2020.

Rough stinkbug (Brochymena quadripustulata) observed in October of 2018.

Backyard lizards

I usually post photos of lizards, usually anoles, in the context of their hunting for insects in the yard. But the lizards in our yard were active in May, which is no surprise. We have had plenty of insects out and about. And I finally got a decent photograph of a skink:

Broadhead skink (Plestiodon laticeps)

I was walking out into the backyard, when this little lady was lying across one of our steps. I slowly backed into the house and grabbed the camera. When I stepped back out, I saw it peering out from the side of the step. I waited a while to see if it would crawl back out, but no go. This is the most social our skinks have been in the yard.

I thought this a five-lined skink, but have learned that female broadhead skinks have stripes, where the males are green with red heads.

Green anole (Anolis carolinensis)

Yes, green anoles can turn brown. I’m not sure why it’s brown when it’s climbing a green plant, but I’m sure it has its reasons. This is our native anole, which has a sleeker head and body than its nonnative cousin.

Brown anole (Anolis sagrei)

Brown anoles, a lizard of Caribbean origin, have squatter, thicker heads. They’re more muscular looking lizards than green anoles, and a little rougher looking overall. I caught this one shedding by the back steps.

Things I saw under lemon tree leaves

As usual, there’s an abundance of life on our Meyer lemon tree. I’ve already shared images of a couple of insects that are eating this tree, and I wouldn’t be surprised if these are also looking to eat some citrus leaf. Or maybe eat the things eating leaves?

Edit January 8, 2021: An iNaturalist user suggested orange spiny whitefly (Aleurocanthus spiniferus). They left a comment on the suggestion asking if this was a citrus tree. I told them that this is our Meyer lemon tree, which they said made the identification more likely. This is a citrus pest of Asian origin.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.