I hate how impressive the wreckage looks. Some of these stumps are visually fascinating; extraterrestrial sculptures beamed onto our beaches. On the west side of Saint Vincent Island, we encounter the sight in the banner image above. You can tell it’s fresher than the stumps on Carrabelle Beach, which the waves have smoothed over time. Here on the island, over a year removed, we can still feel the violence of what happened. Hurricane Michael showed us how sea level rise works.

“Hurricanes are the agents of change.” Says Jeff Chanton. Jeff is an oceanographer at Florida State University, and a renowned expert on sea level rise. As he points out, seas are rising every day, little by little. And then, every few years, in ways not so little. “Shoreline erosion is episodic. It goes along, goes along, goes along, and all of a sudden it will happen in a big way. And that big way is associated with a hurricane.”

Over the course of a day, we follow Jeff along the Forgotten Coast, past many of my favorite places. He shows us how the rising Gulf hits man made structures differently than sand dunes, which are nature’s defense from storm surge and waves, themselves created by waves. Of course, if a storm is strong enough, even dunes wash away.

We also see (and hear) a lot of what makes us love this stretch of Florida coast. Red wolf tracks on a beach. Oyster middens and pottery shards. Migratory birds of every size, from white pelicans and loons to ruddy turnstones and a parula warbler calling from high above us. Any day I drive over the John Gorrie Bridge is a good day.

We start our journey on Carrabelle Beach.

US 98: “…one of the more important, vulnerable places along our coast.”

Jeff is standing with his back to a post. Just over his head, a small sign reads “Hurricane Dennis, Storm Height 2005.”

“Hurricane Michael came through in October 2018,” Jeff says. “Nobody has marked where that came up to.”

In 2005, water higher than an adult man washed over the beach, and over the road alongside it. In 2018, Hurricane Michael washed the road out completely between Carrabelle and East Point. The road was rebuilt. Jeff worries, however, that with the recent frequency of intense storms hitting our coast, the road will have to be rebuilt again. And again.

He walks up to a gully between US Route 98 and a wall of rocks installed to protect it.

“This section of the highway was replaced after Hurricane Michael.” He motions to to a divot in the shoulder, marked by an orange traffic drum. “And here you see the damage to the shoulder that was done in Tropical Storm Nestor in 2019. And you can see that’s eroded almost all the way to the asphalt along the shoulder.”

Less than a year after the road was replaced, a smaller storm sent enough storm surge to remove the earth behind the rock wall. There isn’t much shoulder along the eastbound lane here.

US Route 98 spans almost 1,000 miles from south Florida to Mississippi. In Wakulla and Franklin Counties, it’s the Coastal Trail of the Big Bend Scenic Byway. This stretch ties the Forgotten Coast together, hugging some of the least developed coastline in Florida. To Jeff, it’s this proximity to the water that endangers it.

“I think it’s one of the more important, vulnerable places along our coast here.”

Coastal Erosion and Human Structures

We drive a little further west, stopping to check out the wreckage of a house destroyed by Michael. Again, a rock wall lines the highway. Jeff points out where the rock wall turns and sticks out past the shoreline, letting a house sit out past the current shoreline.

It may not have high rises and condos, but the coast here has been altered by humans. And all of these hard surfaces receive waves more harshly than the sand they’re built on.

“The energy impinges on this very sharply, whereas a natural shoreline would be more gentle.” Jeff says. “And the wave energy would spend itself as it moved more laterally. So when you have a house along the coast where shoreline erosion is occurring, this can be the result, this demolition.”

Sand dunes in particular, built up by waves over thousands of years, protect the habitat behind them. Jeff talks about this when we get to Saint Vincent Island.

“They’re sand banks. They’re like savings accounts for sediment. So when the water comes up, they give up sediment, and they put it up in front of the water, and they arrest the movement of the water on the beach. If the dunes are gone, there’s nothing to inhibit their movement into the back barrier island.”

Beach Erosion is Natural, But…

On the way to Saint Vincent Island, we pick up Jeff’s wife, author Susan Cerulean. I visited the island with them in 2016, to talk about this very topic. Susan’s last book, Coming to Pass, was a love letter to the Forgotten Coast’s barrier islands, which enclose Apalachicola Bay and regulate its salinity (when water’s coming down the river). Susan is also active with the Friends of Saint Vincent Island National Wildlife Refuge.

In 2016, Jeff was about to start measuring shoreline retreat on the island. He explained how a certain amount of erosion on islands is natural, but that sand lost in one place lands somewhere else. An island changes shape and shifts position as it shrinks away on one side and expands on another.

But when it’s shrinking on all sides, and so is the next island, and the beach on the mainland, Jeff sees a clear indication of sea level rise.

“Natural coastal erosion would move sand from one place and put it in another… But on this whole experience from Carrabelle Beach all the way to Saint Vincent Island, all you’ve seen is erosion, right? Everywhere you look there’s coastal erosion. And so there’s something more going on here than just sand shifting around. It’s a one-way retreat of the shoreline. And that’s because of rising sea levels.”

Rising Temperatures and Sea Level Rise

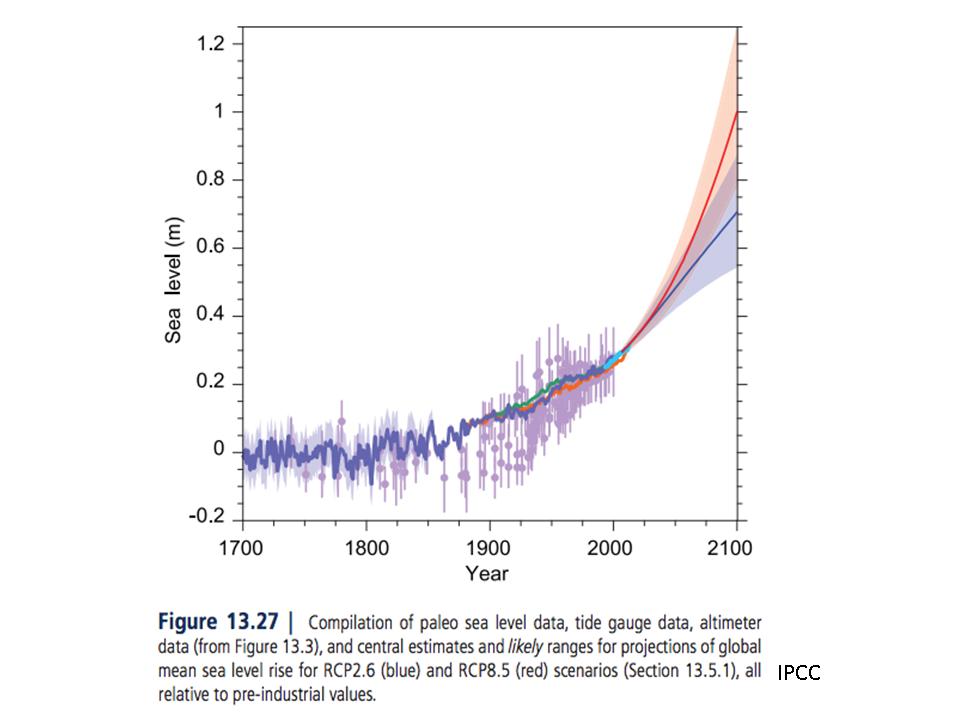

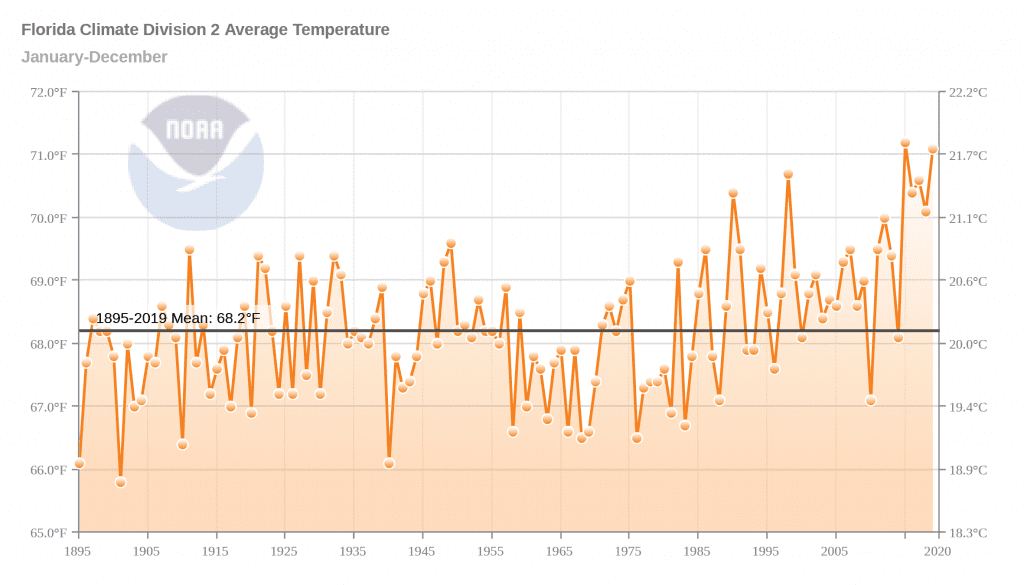

“And in the 1700s, before the industrial revolution, the sea level curve was flat. It wasn’t increasing. Since the 1800s, it’s been a slow, exponential increase. And now it’s at about 3 millimeters per year. And we expect it to increase more rapidly.”

In the 1800s, industrialization, driven by fossil fuels, increased the carbon dioxide in earth’s atmosphere. And since then, deforestation has removed millions of square miles of trees that would have sequestered carbon.

“All the Co2 and methane that’s going into the atmosphere causes the earth to warm up. And that causes the sea level to rise, because the oceans get warmer, and they expand. And the ice caps start to melt, and all that runs into the sea.”

Jeff is talking about this problem globally, but he wanted to measure the effects locally. So he and Susan placed several monuments to measure erosion around Saint Vincent Island, the largest of Apalachicola Bay’s barrier islands.

“When I was measuring it before Hurricane Michael,” Jeff says, “I saw gradual erosion and big, steep scarps, and the movement of the shoreline from year to year. And it was measurable. But then after Hurricane Michael, all the monuments that I put in were washed away.”

It’s not so much that the monuments washed away. The dunes themselves, where Jeff and Susan placed them, had washed away.

The Making of Saint Vincent Island, One Dune Ridge at a Time

We land on the bay side of the island. As Jeff and Susan told me on our first visit here, this is the oldest part of Saint Vincent. Three or four thousand years ago, after the last ice age ended and sea levels stabilized, a small sand bar started to grow. Little bits of the Appalachian mountains drifted from north Georgia, down the Chattahoochee River and into the Apalachicola, before finally flowing out into the Gulf.

Over the following millennia, one by one, new dune ridges formed on the gulf side of the island, expanding it. You can see it in the map above, a series of high sandy streaks with lower forested stripes between them. Freshwater ponds formed in these valleys; here you can find alligators and wading birds.

Saint Vincent is the largest in this chain of barrier islands, and by far the closest to the mainland. It’s only about 400 yards between the Indian pass boat ramp and the boat ramp on the island. And the island has fresh water. It’s natural that indigenous Floridians would have come here to access the bounty of seafood living in Apalachicola Bay.

Before heading out to the wide beaches on the Gulf side, we see evidence of ancient Floridians.

St. Vincent Island in the Late Woodland Period

It doesn’t take Jeff long to find a pot shard in the surf. Behind us, sand has eroded out from under the tree line, exposing roots and vast piles of oyster shells. This is a midden mound, a refuse heap left by the people who came to this island hundreds of years ago. Jeff says these mounds date to about 900 AD, so it was likely made during the same time period as people were inhabiting Byrd Hammock on the St. Marks Refuge, an archeological site I visited a couple of years ago.

Both groups of people would have belonged to the Weeden Island culture. They would have inhabited the coast seasonally, in the cooler months. The middens they left behind show us what they ate, at least the remains of food that hadn’t long decomposed. The sheer number of shells we see now tells us that they came to this area for much the same reason many of us still do.

“They ate a lot of oysters because they could get them pretty easily,” Jeff says, “and they’re delicious.”

Weeden Island people also created pottery decorated with freehand designs; their predecessors, the Swift Creek culture, imprinted pots with wooden stamps.

The inhabitants of the island didn’t build their middens so close to the tide line, where their villages would be more vulnerable to flooding.

“[The middens] used to be higher, they used to be further back in. But as the shoreline retreats, they’re exposed and they erode, too.”

A Wildlife Refuge in Action

Before we head out to the beach, Susan has us stop to listen to a bird call.

“Parula warblers arrived a couple of weeks ago,” she says, “back from their wintering grounds further to the south.”

Early March is a time of transition for the birds of our area. Wintering birds are starting to return north, while birds are arriving from South America just as temperatures start to cool in the Southern Hemisphere. Today, we see and hear birds from each migratory population.

Those birds are the reason Saint Vincent Island was established as a National Wildlife Refuge. As an unusually large barrier island with almost no human structures on it, this is a valuable 12,492 acres of coastal habitat. When we get to the beach, we can see ruddy turnstones mingling with willets and a pair of American oystercatchers. Oystercatchers aren’t migratory, but they are listed as Threatened in Florida. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service website for the Refuge, there are two oystercatcher nests on the island.

The birds share the beach with other animals, like the an otter that flees into the water as we drive by. It left these fresh tracks in the sand:

And then, up on the closest line of trees to the beach, we see a bald eagle. It’s not too far from an eaglet in a nest.

Bald eagle perched along the beach on St. Vincent Island.

Eaglet in its nest.

We’ve had quite a wildlife display in just a short time. But here at the eagle’s nest, we see a cause for concern. There is no dune protecting the tree line.

The Unmaking of Saint Vincent Island, One Dune Ridge at a Time

Without a dune here, a large storm surge would send salt water into the slash pine forest.

“A tree can’t live with its roots in salt water.” Jeff says. “And they’re going to look like those stumps we saw at Carrabelle Beach.”

A little further down the beach, we get a look at a similar, if much newer, collection of stumps and roots than we saw at Carrabelle. We also see signs of one of this island’s signature animals.

Saint Vincent Island is an Island Propagation site in the Red Wolf Recovery Program. Here, captive bred wolves can transition to wild living. If you’re interested in our local connections to this breeding program, it has been a frequent topic on this blog.

After seeing the single row of paw prints, Susan sees five side by side. The island’s whole pack passed through here, a mother and her pups from two litters.

I came here in 2017 to film a segment on the island’s red wolves. Here’s what we saw then when we stood atop the primary dunes on this section of the island:

Now, today, as I’m getting video of the tracks and talking to Susan about the wolves, Jeff says, “Along here where you’ve been taking pictures was the top of a dune. And that’s all where the dune was, all those roots.”

Jeff and Susan point out that this wrecked dune field is now the beach. In a couple of months, sea turtles will start to land on this beach to look for a place to dig a nest. These obstacles might cause them to build their nests closer to the surf, where they’re more vulnerable. So not only is the forest left vulnerable by the destruction of the dune, but one of the beach’s ecosystem services is diminished.

Dunes gather around living trees; their sand held in place by grasses and other vegetation. This is a process that has repeated itself several times over since the island started to form. Hurricane Michael may well have started the reversal of this process.

Wildflowers at the Edge of the Forest

Before we head back, we try to make a trip inwards to get a better look at the interior ridges. A downed tree keeps us from getting too far, but you can see footage of the interior in our 2017 red wolf piece. Anyhow, right near where we have to turn around, we come upon a patch of Gulf Coast lupine. This flower is federally listed as Vulnerable, the level below Endangered.

It’s early March, and it’s only just starting to bloom. This is one is the furthest along:

A couple of weeks later, I visit the Munson Sandhills with the family for a little social distancing adventure. By then, sundial and lady lupines are in full bloom. Sundial lupines are the larval food of the rare frosted elfin butterfly. On that trip, we also saw candyroot, a flower closely related to this one we see not too far from the Gulf Coast lupine:

These related flower species prefer sandy soils. As we saw in a recent post, the Munson Sandhills has been affected by climate change in its own way, with extended droughts affecting the ecology of its ephemeral wetlands.

Jeff and Susan managed to show me quit a lot of what makes this island a special place. Rare flowers, critically endangered predators (tracks, anyway), a host of migratory and resident birds, and on and on. On the boat trip back, we were treated to one last wildlife treat, migratory white pelicans on a slightly submerged sandbar.

As we can see, Saint Vincent Island is still a valuable habitat for a wealth of flora and fauna. But after years of gradual erosion, Hurricane Michael has dealt the island a major blow. The coming years will see how the recently exposed forest copes with storms and flooding. And while more high intensity storms have been hitting our area, we have no way of knowing if and when another storm will tear through dunes, roads, or homes.