Byrd Hammock is an archeological site on the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, Wakulla Beach Unit. Here, archeologists with the Southeast Archeological Center (part of the National Park Service) are trying to solve a mystery…

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

How do you begin to know a person who died over a thousand years ago, and left behind no writing? People lived in north Florida for at least 14,000 years before Hernando de Soto occupied Anhaica in 1539-40. Through the Spanish, we know that the people who lived here then called themselves the Apalachee. We know about their daily lives and religious beliefs, albeit through the biased lens of European witnesses. But at least those clergymen and soldiers lived among and talked to the Apalachee.

There’s no such chronicle for the previous 14,000+ years of life in the panhandle.

I’m standing in a cleared section of hardwood forest with National Park Service archeologist Jeffrey Shanks. We’re two miles from Wakulla Beach in the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, in a place called Byrd Hammock. Jeffrey tells me that we’re in a Weeden Island era village, and nearby is an older village from the Swift Creek culture. They didn’t call themselves that; in fact, we’re not likely to ever know the names of the villages or the people who lived here.

Jeffrey and his colleagues at the Southeast Archeological Center are working on a mystery here. Sometime around 650 AD, people across northwest Florida abandoned their Swift Creek era villages and moved a short distance to create the Weeden Island Villages.

These are likely ancestors of the Apalachee, and what we know of the Apalachee might offer us clues. Archeologists have found a good deal more clues here in piles of shell and cratered mounds outside the village. So while there are no written words, there is a story to be told about these people.

Swift Creek and Weeden Island | Same People, Different Time

So who are these people we call Swift Creek and Weeden Island?

“We call them different cultures, and give them different names- really that’s sort of an artificial, archeological convenience,” says Jeffrey Shanks. “What that means in archeological terms is that their pottery changes. It doesn’t necessarily mean these are different people. They’re actually doing many of the same things.”

Swift Creek existed from around 0 to 600 AD. Weeden Island was around from about 600 to 1,000 AD. Around that 600 AD mark is when, as Jeffrey says, their pottery changes. It also happens to mark approximately when they moved their villages; that the two things happened at about the same time might be significant.

How did archeologists get these dates? The pots themselves can’t be carbon dated. But these pots were cooking vessels, and the food they cooked in them would boil over onto the outside of the pot. Even those small amounts of organic residue could be dated. Archeologists can place dates to the different styles, and start to get a sense of how their culture changed.

But these two culture phases have their similarities as well. The most obvious is that the two have similarly laid out villages. It’s hard to see while standing here, as there are no remaining structures or obvious landmarks. To the untrained eye, the most significant remaining features look like nothing more than a slight rise in the ground. These are the two types of mounds that identify this as a village- midden and burial.

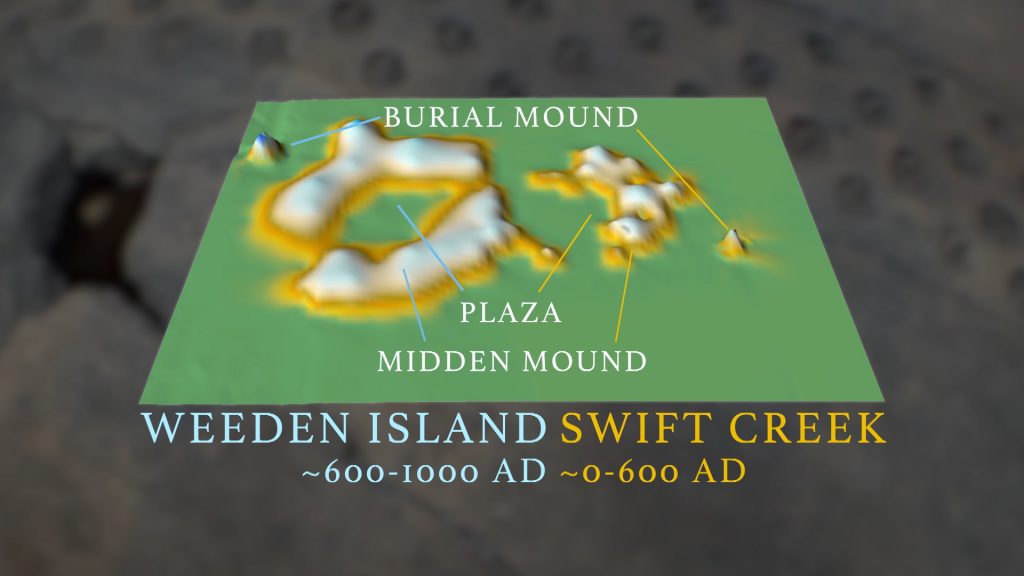

A topographic map of the Byrd Hammock archeological site, provided by the National Park Service. The larger, newer Weeden Island site is on the left, the older Swift Creek village is on the right.

Living in a Ring of Trash

The midden- or trash- mound gives the village its shape. Well, at the time it was created, the village gave the midden its shape. But the houses are gone and the plaza is almost devoid of artifacts, and so the midden helps give us an image of the place where people lived and interacted with each other.

“When I got in the business about 40 years ago, people called shell middens and garbage dumps villages, and I couldn’t understand why,” says Dr. Michael Russo, Jeffrey’s colleague at SEAC. “And that’s because archeologists can typically only look at material remains to identify what the site might have been.”

The remains of a shell midden mound in the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge. Coastal middens in north Florida are usually full of oyster shell.

Wooden houses would have decomposed, but bones, shells, and pottery fragments would remain. So these garbage dumps would be called villages, when really, they’d be next to a village. But Michael thought that middens could tell him something about the empty spaces where people once lived.

“So I started inventing a methodology where, every few feet, systematically, I’d go across an area near a midden to see what the shape of a midden actually was.” He first used this at Archaic period sites which were about 5,000 years old, and discovered that the middens were ring shaped. He found that Woodland era sites (to which both Swift Creek and Weeden Island belong) were also ring shaped.

“Inside the Midden is a generally sterile area where garbage was excluded,” Michael Russo says. What he and Jeffrey visualize is a ring of houses. People threw their trash out the back door, where it accumulated. Inside the ring was a central plaza, a communal space. This is where they’d perform ceremonies, so they kept the area free of trash.

A crown conch shell on the Weeden Island midden at Byrd Hammock. I think that red dot is a chigger (you can see it moving in the video). This gives you an idea of the working conditions here- it’s an area full of ticks and chiggers.

At Byrd Hammock, “Garbage Doesn’t Lie”

The midden shape gives us some ideas about what a village was like. But the contents of a midden can also tell us quite a bit about life at the time. And so while the people living at Byrd Hammock left no texts, the information they did leave might be more truthful than written words.

“Historical texts may lie,” says Jeffrey Shanks, “but garbage doesn’t lie.”

As Michael Russo says in the video, the garbage dumps mostly contain food related refuse. Meats and veggies decompose; bones and shells remain. Located two miles from Wakulla Beach (where we’ve previously documented oyster research), it’s no surprise that most of the shells are oyster, or species that live on oyster reefs, like crown conch.

There are also deer bones, which can tell us a few things about the behavior of village inhabitants.

“Deer shed their antlers,” says Thadra Stanton, who specializes in lithics (rocks) at SEAC. “And so when we find the presence of a skull with the antlers still attached, we know what time of year it was… and so that gives us an idea of what time of year the deer was killed.

“That gives us an idea of what time of year they were occupying these sites. And from that we can tell how they were moving across the area.”

Now we can visualize our mystery people traveling between different village sites, perhaps as different food sources became seasonally available, or as sites became more comfortable (think of the yellow flies near the coast during summer months). Other artifacts found in middens can give us a much more, um, intimate look at the occupants of these sites.

An artifact known as a coprolite, which is exactly what it looks like. This was found in a midden at the Spring Creek archeological site at the St. Marks Refuge.

In 1,000 Years, an Archeologist Might Be Interested in Your Poop

“One of the interesting items is coprolites.” Says Thadra Stanton, “Which is poop.”

Standing in the plaza of Byrd Hammock’s Weeden Island village, Jeffrey Shanks paints us a picture of how village inhabitants used the midden.

“When they went out back to take a poop, it was probably on the midden.” The midden would have had rotting fish carcasses, decomposing deer flesh, fresh oyster and conch shells as well. “I imagine it would have been pretty nasty for us.” The midden ringed the village, and from what they can tell, there was no walkway through it. They’d have to climb over the mound to get into and out of the village.

So now, in addition to being able to visualize a little about village life, we can smell it, too.

While these were not an agricultural people, they seem to have had a great compost pile going (And yes, there are people who use their waste in compost, though they do take steps to ensure food safety). Of the foods they ate, we can only see the remains of shells and bone; everything else turned into a dark soil. And since this village was built on sand, this organic soil is a midden indicator.

Left, a tree at the center of Byrd Hammock’s Weeden Island village was uprooted during Hurricane Hermine. This exposed the sand under the leaf litter. On the right, we can see the soil in the midden surrounding the plaza, black from decomposed organic matter.

Not all of the garbage in the midden mound is organic. They also threw away pots when they broke, and other unused art materials. Let’s move away from the trash pile now, and take a closer look at the things they made.

Swift Creek Pottery

As Jeffrey hinted, the main reason “Swift Creek” became “Weeden Island” is that their pottery changed. Over the roughly one thousand years these two cultures occupied northwest Florida, their pottery changed quite a bit. This is normal; we would expect any culture to evolve over so long a stretch of time. But what the Weeden Island culture did with its pottery is unique, and has a lot to tell us about why they moved their villages.

Let’s start with a look at the older Swift Creek pottery. Swift Creek people stamped patterns into their pots before firing them, usually with a wooden paddle. Thadra Stanton showed us how the paddles became increasingly complicated over time.

Over hundreds of years, the designs on Swift Creek paddles grew more elaborate.

Of course, these aren’t the original paddles; those were mostly made of wood and long ago decomposed- except those found in wet environments. We’ve previously covered how wet sediments, lacking the decomposing effects of oxygen, better preserve artifacts. Between that, and looking closely at the texture of the stamp, they knew that these were wooden paddles. SEAC then had artists backwards engineer the patterns from the pots and onto paddles.

As Thadra Stanton says, the patterns are diagnostic. Once a pattern is dated on one pot, they have a rough idea of the ages of other pots with a matching pattern. And we’re talking about an exact match- not that the same design was used, but that the same irregularities, wood grain and all show that they’re from the same paddle.

Left- mica, a rock not found locally, obtained via trade. Weeden Island people would decorate these with etchings. Left, you can see specks of mica in a clay pot.

Trading Goods with the Midwest and Beyond

Some patterns show up at multiple sites across the area, meaning that pots or paddles were traded, or that the potter traveled with their paddle. The Swift Creek people were part of a wide trade network called the Hopewell Interaction Sphere.

“We have pottery on up in Indiana, Ohio, that area, that’s identical to the pottery that’s being made down here.” Says Michael Russo.

The patterns on some pots show evidence of other traded goods. “They would use corn and corncobs to mark their pottery as well,” Thadra says. Corn likely started out as a grain called teosinte, which increased in size through selective breeding in what is now Mexico. “What’s fascinating for us is the size difference. You can actually see the kernels of the corn in the wet clay; and then, over time, you can see how the corn has gotten larger.”

We’ve previously covered how the Apalachee traded lightning whelks inland, where they were an exotic luxury item. This went on as early as the Swift Creek period. In return, they received materials not available here, rocks such as mica which they then inscribed.

A Change in Pottery Style, a Change in Name

The Swift Creek people had been making increasingly complex paddles. After a time, they started taking more time to decorate pots, inscribing them by hand.

Here you see a punctuated pot, where a potter poked a pattern around not the whole pot, but the band.

Over time, they started freehand drawing, which would take even longer to do.

So, the artistic style changes. That’s not insignificant. But it’s the next leap in their pottery design that gives us our first major clue into why the inhabitants of Byrd Hammock, along with their counterparts across northwest Florida, moved their villages.

This pot here has no functional purpose. You wouldn’t cook food in it, or use it to transport goods. It’s one of a new class of pots like this that show up in Weeden Island burial mounds.

“These Weeden Island mortuary ceramics… these are something special.” Says Jeffrey Shanks. “This is not a normal, everyday occurrence, creating an entire class of objects just made to be buried in a mound with the deceased. So something’s changing about their afterlife beliefs, about their funeral practices.”

This is a big part of what makes Weeden Island distinct from Swift Creek. Taking our cue from this change in burial practices, we start to see some other differences.

A Change in Pottery Style, a Change in Religion?

Earlier, I mentioned that Swift Creek and Weeden Island used similar village layouts. Similar, but not exact. Both had a ring or c-shaped midden mound, and a burial mound nearby. But let’s take a closer look.

The Weeden Island midden is larger, implying that the village inside, and its central plaza, is larger as well. Then there’s the position of the burial mound.

“One of the things we’re starting to see with Weeden Island sites is that their mounds may have a solar alignment in relation to the village.” Jeffrey says. “In several of the Weeden Island sites that we’ve found, the burial mound would be located in an area so that if you were standing in the center of the plaza in the village, the sun would set behind the mound on the Winter Solstice.”

Weeden Island people always buried their mortuary ceramics on the southeast side of the burial mound. “That would be the side the sun would rise over on the summer Solstice, and shine on it.”

Archeologists may be seeing the beginnings of religious beliefs that lasted for several hundred more years. “When the Spanish did come to the area, from what we know about the religion of the people they encountered, there was very much a solar aspect to it.”

Hernando de Soto’s famous first Christmas in the Americas, in modern day Myers Park, would have taken place just after the Apalachee celebrated the winter solstice. At least, they would celebrated if they weren’t busy shooting arrows at their unwanted guest.

That’s One Possible Story…

Jeffrey Shanks is the first to admit that this is all speculation. He and the other archeologists at the Southeast Archeological Center won’t find a scroll at a Weeden Island site that says “All hail our new Sun God!” So there’s not likely to be a definitive answer to the question “Why did they move?”

On the other hand, a lot of careful and meticulous work has been done to collect the clues we’ve reviewed today. They excavate in defined layers, carefully record the exact position of every artifact found, and the sediment layer it’s in. They’ve used artistic and radiocarbon analysis of the pots to learn about their creation. Looking at archeological sites across the country, and more locally within our region, they have this idea of the larger world which our local people inhabited.

They know they’re guessing, but it’s an educated guess.

And there’s still much more to discover. Jeffrey thinks they changed religions and so moved their villages a few feet away to accommodate their new beliefs. Michael Russo thinks this possible new religion came in with an outside group of people, who mixed with the Swift Creek to create a new culture. This would explain the larger empty space inside the midden mound, housing a larger village with more people. Or was it merely that they needed more space for new ceremonies?

Uncovering the Story of Northwest Florida

The more of these questions they can answer, the better sense we get of the history of people in our area.

As a person of Spanish descent, I know the history of the places in north Spain where my family comes from. One day I googled my last name and found a Diaz de Villegas castle in Santander, in the province of Cantabria, built around 1500 AD. When the Swift Creek were living in Byrd Hammock, Cantabria was a part of the Roman province of Tarraconensis. A few thousand years before that, Celts passed through Basque Spain and mingled with my maternal grandfather’s ancestors (my aunt recently did a DNA genealogy test which showed some Celtic descent).

We don’t have that kind of knowledge about the people who lived here. We’ll never know what they called their village in Byrd Hammock, or what they called themselves. But it’s worth knowing how people lived in this area before longleaf forests were clearcut, when red wolves and Florida panthers roamed northwest Florida.

In part two of our story, we learn how Jeffrey and Michael deduced the general location of a Swift Creek village and how they found it. We also learn how looters affect an archeologist’s ability to gain meaningful information from a site. All that and more, coming up towards the end of May.