Last year, an archeological site on the Aucilla River made international news when an artifact was found in sediment radiocarbon dated to 14,550 years ago. This makes it one of the oldest sites in North America, further evidence that people were here earlier than once believed. We catch up with the research team behind that find. Our area is a hotbed for underwater archeology; in fact, our many waterways might be our greatest archeological asset.

Special thanks to Shawn Joy, Morgan Smith, and Matt Vinzant of Karst Underwater Research for letting us use their underwater footage. Morgan’s research is sponsored by the Felburn Foundation, Center for the Study of the First Americans, Texas A&M University, and the PaleoWest Foundation. He would like to thank the Silver River State Park, Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Subscribe to receive more videos and articles about the natural wonders of our area.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

“Ocala famous, baby!” Shawn says as he and Morgan look over the cover of the Ocala Star Banner. In one photo, the two of them are beneath the Silver River in scuba gear, under the headline “Unearthing History”. Excavating a submerged mammoth kill site might be as glamorous as prehistoric archeology gets, and it looks good on the newsstand.

A few feet from Shawn and Morgan, Dr. Michael Faught is labeling bags with small bits of rock and soil. Much less glamorous, but critical work nonetheless.

The public reacts to mammoth bones and projectile points. And those are important. But the story of this archeological site will also be told by rock flakes, seeds, and the bones of smaller animals. From these, Morgan Smith will learn important details about a people who may have killed a mammoth here over 11,000 years ago.

I’ve arrived at Silver Springs State Park on a day off for Morgan and his crew. They’re hanging out and taking care of miscellaneous tasks at their one-room dormitory. “This is kind of like being at summer camp.” Morgan says, “We all have bunk beds here. We’re all sleeping on top of stuff.”

As you can see in the video, it’s a bit messy. It’s a small space for that many people, not to mention their scuba gear and other scientific accoutrements. The state of their dorm is in stark contrast to their excavation methods, however. To get meaningful information from a muddy river bank, they have to be meticulous.

This crew is as experienced as any in the small but growing field of underwater prehistoric archeology. Morgan and Adam Burke are PhD Students at Texas A&M University. Jesse Halligan and Michael Faught hold PhDs, and Shawn Joy is Jesse’s masters student at Florida State University. They’ve worked on some high profile sites that are causing people to rethink how humans first came to the Americas.

The sediment layer we see being excavated is divided into numbered plots, marked by the tape we see here. The riverbank is excavated one unit at a time, and the exact location of every excavated item is recorded by divers underwater.

The Guest Mammoth Site | Underwater Archeology Ahead of it’s Time

Morgan’s two Silver River sites were first found in the 1960s and 70s, well before Michael Faught and Jim Dunbar began the modern era of submerged prehistoric archeology in 1986. The first site, at the head spring of the river, has a lot of mammoth bones and artifacts. But it lacks context (we’ll examine the context issue in more depth next week). The second site, however, was ahead of its time.

It was discovered 1973 by truck driver George Guest, who found bones sticking out of the river bank while diving. The site was excavated by Charles Hoffman, then at the University of Florida. His was the first dig of its kind in North America; scuba was relatively new and he had to figure out how to translate what he knew about excavation to an underwater setting.

Hoffman found paleo-Indian projectile points alongside the bones of Columbian mammoths. At the time, it wasn’t believed that humans had interacted with large prehistoric mammals- megafauna- east of the Mississippi. Columbian mammoths went extinct about 11,000 years ago; having humans here before that would put them in the southeast earlier than previously thought.

This, in turn, would put humans on the continent earlier. And in 1973, the idea seemed impossible. Additionally, Hoffman was betrayed by the radiocarbon technology of the time, which didn’t adequately filter out contaminants from underwater samples. His mammoth bones dated to after the extinction of the species.

But the biggest thing working against Hoffman might have been that he was trying something new. Many doubted that underwater excavation could be scientific. And when his results didn’t line up with the thinking of the day, they were easily dismissed.

Rethinking the Land Bridge Theory

Things have come a long way for underwater archeology over the last few decades.

“We’re in a totally different mindset today than we were back then.” Morgan says, “We’re starting to realize how little we do know, when these sites in South America appear, and these sites in Florida appear, that just totally break the paradigms.”

“These sites in Florida” refers to sites like Page-Ladson on the Aucilla River. Last year, Dr. Jesse Halligan and Dr. Michael Waters (Morgan’s advisor at Texas A&M) revealed their big find there: a chert knife was found in sediment radiocarbon dated to 14,550 years ago. (The graphic in the video above incorrectly states that the knife itself was dated- in fact it was organic sediments around the knife that were dated. Only organic material can be radiocarbon dated.)

A site at Monteverde, Chile is widely accepted to be about as old as Page-Ladson (and some disputed evidence dates it as much older).

Why is this a big deal? Until fairly recently, there was only believed to have been one way into the prehistoric Americas- a land bridge connecting Alaska and Siberia. People migrating through Beringia, as this bridge is known (because there was dry land across the Bering Straights) likely came over between 15,000 and 14,000 years ago.

“Everybody still believes that people came across the land bridge into the Americas,” Morgan says. “And that is the primary migration wave… [but] it doesn’t make much sense for a Beringia model of people entering first and coming down and basically sprinting down to South America to have these early sites.”

“When we see people migrating across Beringia, which we do,” says Michael Faught, “There’s people already here in the new world.”

Who Were the First Americans?

Who were these mysterious First Americans? And how did they get here?

“They could be coming out of Southeast Asia,” Says Dr. Faught. “Because [the southeast Asians of the time are] more likely to be maritime involved. They’re more likely to be able to cross the ocean or follow the coastline and come around.”

Because many of the oldest New World sites are in Florida and South America, people are considering alternate places of origin for the First Americans. Some are looking to Europe, and an Atlantic crossing to the American southeast- for more on this debate, check out our 2015 post on one of Morgan’s digs.

As for the early South American sites, Dr. Faught has another theory. “There’s a third population possibility in Brazil that have skeletal similarities to Africans or Australians. And Africa is close to Brazil.”

The genetic evidence points to Asia as the origin for existing Paleo-Indian fossils and modern native Americans. But that doesn’t mean there weren’t smaller groups that came and died off.

And the fact that there are older sites in Florida than in most other places in North America doesn’t mean that there aren’t earlier sites out west. What those potential sites don’t have is the access and preservation offered by one key resource: Florida’s abundant waterways.

Is Florida’s Greatest Archeological Asset Its Water?

Which brings us back to the Guest Mammoth site. The Silver River originates in Silver Springs State Park, at a spring called Mammoth Spring. The Guest site is at the confluence of the Silver River and another river.

Imagine if you will what this area might have looked like over 11,000 years ago. “Instead of the Silver River running fully like it is today,” Morgan says, “it would have been reduced to this series of ponds. And mammoths and people aggregated around these ponds.”

So the encounter between Paleo-Indians and the mammoths who left these bones didn’t happen underwater. Over time, however, the springs feeding the ponds formed a river, and the river encased this scene under layers of sediment deposited over millennia. During this time, the river channel continues to move, and every once in a while buried fossils and artifacts start to stick out of the bank.

This is why an amateur diver was able to spot mammoth bones in the river bank. It’s also why Ryan and Harley Means found spear points at the bottom of the Wacissa River, leading to the discovery of the other site we see in the video.

Our aquatic environments preserve bones and artifacts better than those buried in dry land. “It’s hot, it’s cold, it’s wet, it’s dry all the time on land.” Morgan says. “And you don’t get the stability that you need for organic preservation. Underwater you get that stability.”

Florida rivers have a consistent Ph level, and, especially in spring fed rivers, consistent temperatures. The way rivers deposit layers of sediment is also key to archeologists- and we’ll get into that more next week. The thing to consider is that older sites in Florida don’t mean that people were here first, it just means that these are better sites for archeologists.

The skeleton of a Columbian mammoth, on display at the Silver River Museum at Silver Springs State Park.

Columbian Mammoths and Mastodons | Florida’s Ancient Elephants

Part of what we can learn about the Silver Springs area of 11,000 years ago comes from the animals that lived there. We can learn a lot from the star attraction of Morgan’s Silver Springs sites.

“It’s interesting that we have mammoths down here,” Morgan says. “In the Silver River it seems like we have more mammoths than most other places in Florida, where you have mastodons.”

This mastodon skeleton was found at the bottom of Wakulla Spring. It is currently on display at the Florida Museum of History in Tallahassee.

Mammoths and mastodons are ice age relatives of elephants whose fossils we find in Florida. Even during the ice ages, Florida isn’t covered in snow and ice. So we didn’t have the more widely known wooly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). Instead, we had the slightly smaller, less hairy Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi).

American mastodons (Mammut americanum) are more closely related to mammoths than either is to modern elephants. Since each species had different feeding habits, finding one or the other tells us about the environment of a site. Mastodons are, like today’s elephants, “browsers.” They ate leaves off of shrubs and bushes, as indicated by the sharp cusps of their teeth.

Columbian mammoths, with their flat teeth for grinding grasses, were grazers. Finding them “indicates that the Silver River had to have been a dry, open grassland type of area.”

Adapting to a Changing Landscape

These, and other large mammals of the era, died out between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. This coincides roughly with a climate event called the Younger Dryas, which was an interruption in warming temperatures at the end of the last ice age. Changing climate is one possible reason they died out. The growing number of Paleolithic hunters might also have played a role.

Either way, Paleo-Indians entered an American landscape undergoing dramatic transformation. It’s part of what excites Morgan about his dissertation work on his Wacissa site. Here, a people from the Suwannee Culture once camped and left a few tools and spear points.

“The Suwannee people would have witnessed the most dramatic climate change the earth has seen in recent memory.” Morgan says. “They’re an excellent correlate for adaptation to climate change like we’re seeing right now.”

Not only were the plants and animals around them changing, Florida was in the process of forming its trademark shape. “Of course, the sea level was quite [a bit lower].” says Michael Faught. “There were 70-80 miles more of Florida to the West Coast than there are today.”

As you can see on this Google map, there is a wide continental shelf off Florida’s Gulf coast. When people were hunting mammoths on the Silver River, or making tools by the Wacissa River, they were also out on this shelf, which was dry land.

“You have Suwannee points a hundred miles off the coast,” Morgan says. “You have Suwanne points inland.”

Michael Faught believes the best sites might be out there off the coast, where they’re less likely to be disturbed than in rivers. He and Shawn Joy have a grant application in to start exploring. If they get it, we might be looking to tag along and see if we can learn a little more about Florida’s ancient past.

Next Week

On part two of this underwater prehistory adventure, we revisit the Ryan-Harley site with Ryan and Harley Means. We ask the question: what makes one site scientifically significant, and another just a cool pile of bones and points? And we look at the role of divers like George Guest and Ryan and Harley Means, who find significant items in rivers. Morgan shares his thoughts on citizen involvement in archeology.

We’ll leave you with a few photos of the Silver River Museum, located in Silver Springs State Park. They have an impressive collection of Pleistocene fossils and artifacts, as well as items from several eras of Florida history.

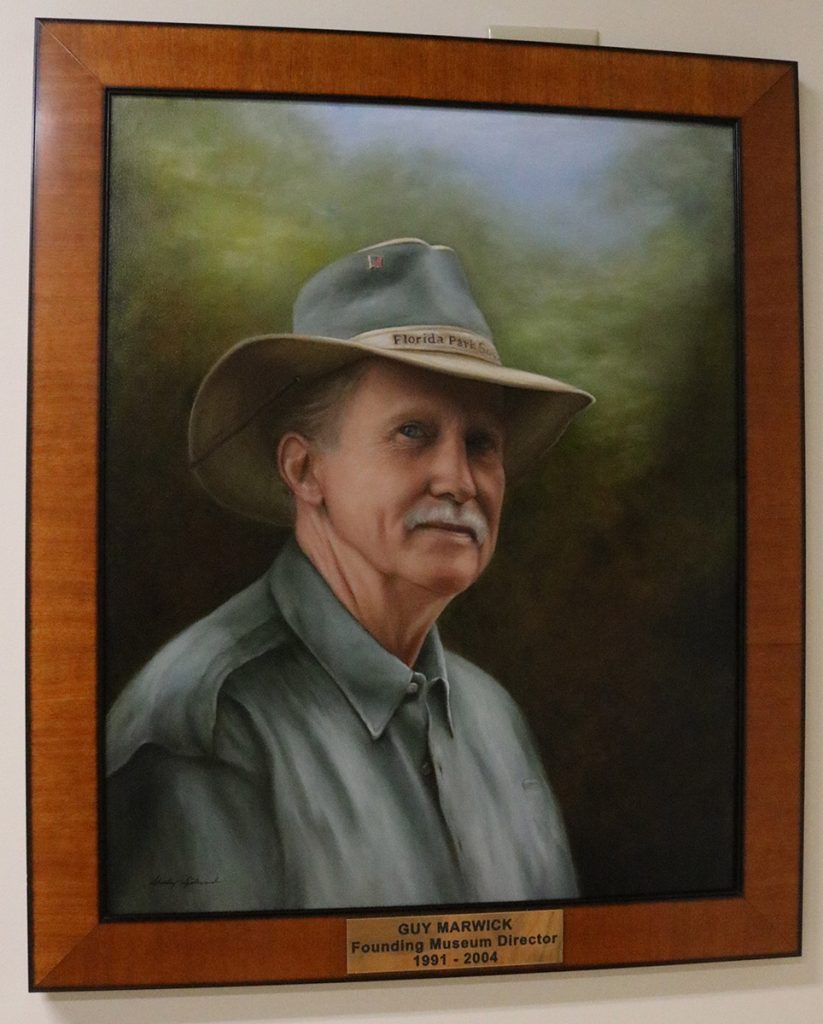

Guy Marwick guided us through the museum. Many of the prehistoric items we saw came from his personal collection.