Often, what we stop looking for, we find. Not that I was looking for the bee I found at Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. That bee isn’t supposed to be in Florida; but – and this may be hard for folks to understand – that’s why I was looking for it.

I like finding rare and uncommon bees.

Earlier this year, I produced a segment on iNaturalist data. Dave Almquist of the Florida Natural Areas Inventory gave me a map of potential sites for a recently discovered, specialist bee. The sandhills cellophane bee has an affinity for climbing fetterbush flowers, and a specific nesting habitat with its own associated plants. Dave made the map using iNaturalist observations for the plants, and I found a new site for the bees.

That site was not far from the Munson Sandhills, where I’ve found a couple of other rare/ uncommon bees. Part of what makes these bees uncommon is that they’re specialists. They have a relationship with certain flowers. In many cases, they also need a specific kind of soil, open space, or dead plant material to make nests.

Specialists can’t live just anywhere, and that’s the fun of finding them. One specialist, the blueberry digger bee, visits my yard every spring when my blueberry bushes bloom. But most specialists require a trip to the forest, and a little exploring. Because of their specialized needs, when I learn about them, I learn about their environments. Specialist bees – any specialist animals – are a gateway to a deeper appreciation for a habitat.

So far, the habitats where I’ve found specialist bees were sandhills. Sandhills were once beach dunes, and they lie on ancient coastlines. The Munson Sandhills are currently a couple dozen miles from the coast, south of Tallahassee. Like many ecosystems in the American southeast, sandhills are dominated by longleaf pine and wiregrass, and are fire-dependent. This means the cycles of the plants and the balance of the ecosystem are tied to regular fire.

The search for rare and specialized bees

After that iNaturalist segment, I wanted to look for more rare bees. Instead, I spent the summer editing a documentary. Shameless plug: it’s called Finding the First Floridians, and it airs on December 18, at 8 pm ET, on WFSU-TV. It’s about prehistoric archeology in Florida.

When I finished editing, I took a look at a link someone shared in the Ecology Blog’s comments section. It’s a list of specialist bees in the eastern United States. I looked for bees that were in Florida, and that flew in October and November. I also looked at the host flowers, and many of the Florida bees visited the same ones, in particular silkgrass (Pityopsis) and goldenasters (Chrysopsis).

Since so many shared those two flowers, I looked for where I could find the most.

iNaturalist is a free app you can use to help you identify plants and animals, but it also stores those observations for anyone to sort through. I made a map of observations for the two flower species in Leon County, and found that the largest concentrations were right in the Munson Sandhills. Where I’ve already found rare species. Perfect!

I went a couple of times and photographed several cool bees, but nothing on the list.

And then I got busy again.

Well, maybe next year.

An unexpected encounter at the Tall Timbers burn plots

I had another documentary project to edit and other stories to pursue. And so I found myself at Tall Timbers recording footage of shortleaf pine/ oak/ hickory habitat. This is also a fire-dependent ecosystem. My host was Dr. Jean Huffman, who is looking to restore this type of habitat next to her house in the Miccosukee Land Coop. She and her neighbors are trying to turn that property into a preserve, but it needs work. Tall Timbers has an example of this habitat, to show us what the Hickory Preserve should look like after restoration.

Leaving that habitat, we stopped at one of Tall Timbers’ seasonal burn plots. There are eight of them, eight squares that are each divided into four smaller squares. That’s one for each season. Every year, they burn one square in winter, one in spring, another in summer, and a final one in the fall. Researchers then study how the habitat responds to fire in each season.

As I was shooting footage of a summer plot, I saw an insect I’d never seen before. It was on a goldenrod flower, and it looked like a yellowjacket, but it had a bee shape. The camera was on the tripod, and I didn’t want the insect to fly away before I got a photo. So I made a snap call to take out my phone and snap some quick photos. I regret that they’re phone photos, but at least I had them.

I uploaded the photos to iNaturalist and selected the app’s top suggestion: yellow jacket. But I wasn’t sure. I had no time to dwell on it, though. It was a Friday, and I spent the weekend camping. As I kayaked the Suwannee River and ate shrimp boil by the fire, a few iNaturalist users chimed in with suggestions. One of them was iNaturalist’s top bee curator, Dr. John Ascher. It turns out I had seen a southeastern sunflower burrowing-resin bee (Paranthidium jugatorium ssp. lepidum).

Not only that, but Dr. Ascher thought it might be the first record of the bee in Florida. I checked, and it was only the second. The first observation was made four years ago, on the other side of Lake Iamonia from Tall Timbers. The next nearest observation was hundreds of miles away.

Why so small a Florida population? (or is it small?)

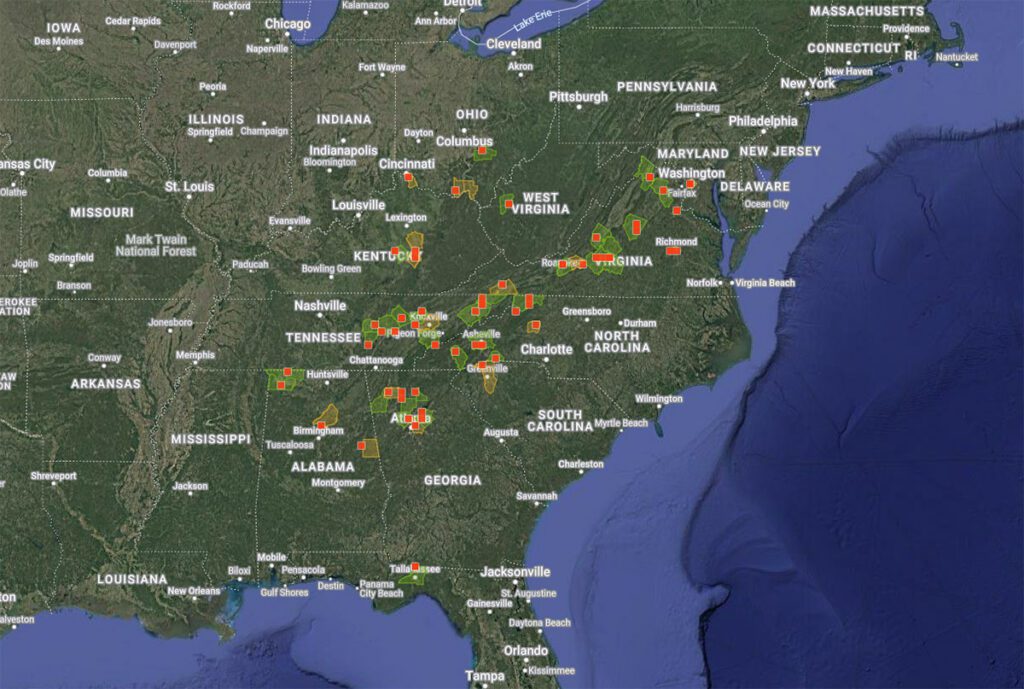

The range for this bee starts around Atlanta, Georgia, and extends into southern New England. The bee is on the list of specialists I mentioned, where it is classified as uncommon/ rare. I may have paused my search for rare bees, but I never stop looking at anything I see flying near a flower. And I never stop visiting wild spaces.

The only two observations for hundreds of miles are only 5 miles from each other. Why do these bees seemingly like this little patch north of Tallahassee, and nowhere else near it? I wanted to know more, so I returned to the site a few days later, on November 13. The bees were still on the same summer burn plot, but only in flight, never on flowers. I’d often lose them as they went to ground under the stems of a wildflower or a beautyberry bush. It’s late in the year, and bees are nesting. I likely won’t be able to see the bee again for a few months.

It’s not a mystery I’ll solve anytime soon. In the meantime, we have some information about the bee and its habitat. It’s no accident that I only found the bee in a summer burn plot. But why?

The southeastern sunflower burrowing-resin bee: what do we know?

- I observed the bee on November 8. It’s the only iNaturalist observation for the bee in November. The other Florida observation was made in October of 2020. Throughout its range, the bee appears in the summer, peaks in August, and declines sharply in September.

- The sunflower burrowing-resin bee’s range extends from the Atlanta area to New England. There are also scattered populations out west. There are four subspecies that cover different parts of the range. The “southeast” subspecies is limited to the southeast – between Atlanta and Maryland.

- It has sunflower in its name, and that is one of the flowers it visits. It’s a specialist of Asteraceae, the sunflower family, which includes sunflowers, rosinweeds, goldenrods, silkgrasses, goldenasters, etc.. I found it on goldenrod, one of the last flowers to bloom in our forests.

- Resin bees are Megachilidae, a family of bees that includes leafcutter bees and mason bees. The names refer to the materials they use to line their nest walls. Resin bees in the genus Paranthidium nest in sandy soils, lining the walls of their nests with resin. Like other Megachilidae, their nests are long tubes, a series of cells containing a single egg surrounded by pollen. Paranthidium separate each cell with small pebbles.

This gives us some idea of what the bee needs to survive. How does that line up with the habitat?

Seasonal burn plots at Tall Timbers

I was there to video each of the burn plots, and comparing the plots is a good place to start.

The plots are located within an area dominated by shortleaf pine, along with some longleaf, slash, and loblolly pines, and hardwoods. Without getting overly technical, it’s a version of the shortleaf/ oak/ hickory habitat that I was there to film. Within the burn plots, Tall Timbers has also planted young longleaf pine trees.

Right off the bat, we can see why the winter and fall plots would be less attractive to a bee. The winter plot is full of shrubs, which leaves less space for wildflowers. Not much is in bloom. The fall plots had been too recently burned.

The spring and summer plots look similar until you zoom in. The spring plot is slightly shrubbier, but still has plenty of wildflowers. More of them, though, are blooming in the summer plot. In June or July, every wildflower burned to the ground in this plot. They then either resprouted from their roots or fresh from seed. Because they started growing later than the flowers in the spring plot, they bloomed later. This explains why I saw more bees here in November than in any other part of the property.

The ground is also more open in the summer plot than it is in the spring plot. More open ground means more places for a burrowing bee to make a nest.

Chasing after the bees into the interior of the summer burn plot, I found several nest openings that would accommodate the size of the bee.

Still much to learn about this bee in Florida

The summer burn plot had more late-blooming flowers, and more open space on the ground than the land around it. More food, and more places to shelter. It’s a quick, simple answer – a place to start. It is now mid-November, and the bees are either done for the year or soon will be.

Late-blooming flowers and open ground can’t be the entire answer, because a lot of habitat in our area would meet these requirements. The Apalachicola National Forest, especially in the Munson Sandhills, has plenty of open ground and plenty of bee diversity. And throughout its range, Paranthidium jugatorium isn’t a late-flying bee. There’s some other factor limiting them to this small area.

It’s worth returning to check out the habitat, and I hope I can next year. For anyone who likes to iNaturalize bees in Leon and the surrounding counties, keep an eye out for this bee. It might well be in more places than we suspect. This is why I like to photograph bees and other insects. Most people tend to overlook them, but, especially in as biodiverse place as north Florida, there are always rare, endemic, and otherwise odd insects all around us. We have only to look.

Other insects of the summer burn plot

The summer plot has many herbaceous plants and plenty of open space. That’s good for bees, and for other insects, too. What else did I find when I was looking for bees?

Leaf-footed bugs are plant-eating insects.

Blister beetles secrete a toxin to defend themselves, one that blisters the skin. The last two photos are from my second trip to the burn plots. Just five days after my first visit, the goldenrod blooms started to turn to seed.

Where we see a lot of plant-consuming insects, their predators are never far away. This is a type of assassin bug.

Scorpionflies eat dead and dying insects, as well as pollen and nectar. This one seems to be eating something under the leaf, which I didn’t notice at the time I took the photo.

Green lynx spiders are hard to see on yellow flowers, where they often wait for bees and other pollinators. At this time of year, they have bred and are carrying eggs on their backs. The mother will start to turn brown, the color of this seedhead, and the sacs will open up and release dozens of little spiders.

This is not an insect, but I wanted to close with this image. I think of this as Florida snow. You have seen several flower seedheads in this post; many are feathery and light-colored. A good wind will disperse the seeds onto earth made bare by fire, where many of them will grow. bloom, and feed southeastern sunflower burrowing-resin bees.

As fall turns to winter, this is what many Florida wildflowers will become.