How does one attempt to find the rare and specialized sandhills cellophane bee? It’s the kind of story our Ecology Producer always hopes for. This segment was produced in collaboration with NOVA | PBS. All photos by Rob Diaz de Villegas unless otherwise specified.

A couple months ago, I decided to undertake a mission. It started with a curiosity: I wanted to know how researchers use iNaturalist data. This wasn’t the mission – it was a segment idea, but it led me there. I talked to biologists to identify species of interest to them, things I could find as winter turned to spring. The plants and animals they told me about all happened to be inhabitants of the sandhill habitat.

The first was a butterfly familiar to me. The frosted elfin is disappearing from its range, and researchers are searching for its host plant. The more places they find sundial lupine, the more places where they might find elfins trying to lay eggs on them.

Next, I talked to botanists who recently discovered three new species of lupines. Many of the plants had previously been identified as other lupine species; now researchers are reclassifying existing iNaturalist records and seeking out new locations. The new species are in the Florida peninsula, far from where I live.

Then there’s the sandhills cellophane bee. This bee was discovered a few years ago, yet it doesn’t have many known sites. Like the species I previously mentioned, it’s a sandhill inhabitant. But it specializes in the flower of a plant that grows in cypress wetlands. It needs the two habitats in close proximity, which limits the potential locations where we might find it.

I love photographing bees, especially when I can find a rare or uncommon species. The sandhills cellophane bee – this was the mission.

iNaturalist and the Florida Natural Areas Inventory

I was introduced to the sandhills cellophane bee by Dave Almquist, Invertebrate Zoologist for the Florida Natural Areas Inventory. FNAI operates out of Florida State University, and its job is to know where to find all of the state’s coolest plants and animals.

“We are a natural heritage program,” says Mitchell East, FNAI’s data manager. “Each state in the US has a natural heritage program, and each one maintains a database of locations for species of conservation value and will assign conservation ranks to each of those species.”

By FNAI’s definition, species of conservation value are rare and imperiled. Most locations in their database were found by FNAI or other biologists. This is, to me, the best kind of work: trudging through swamps, marshes, ephemeral wetlands, and, yes, sandhills, in the pursuit of rare living things. I know not every location is so adventurous, but it’s rewarding to find rare species in the wild.

It’s rewarding to me, anyway. That’s why, even though I’m not a biologist, some of the locations in their database came from my own adventures. Mitchell pulls up a map and populates it with yellow dots.

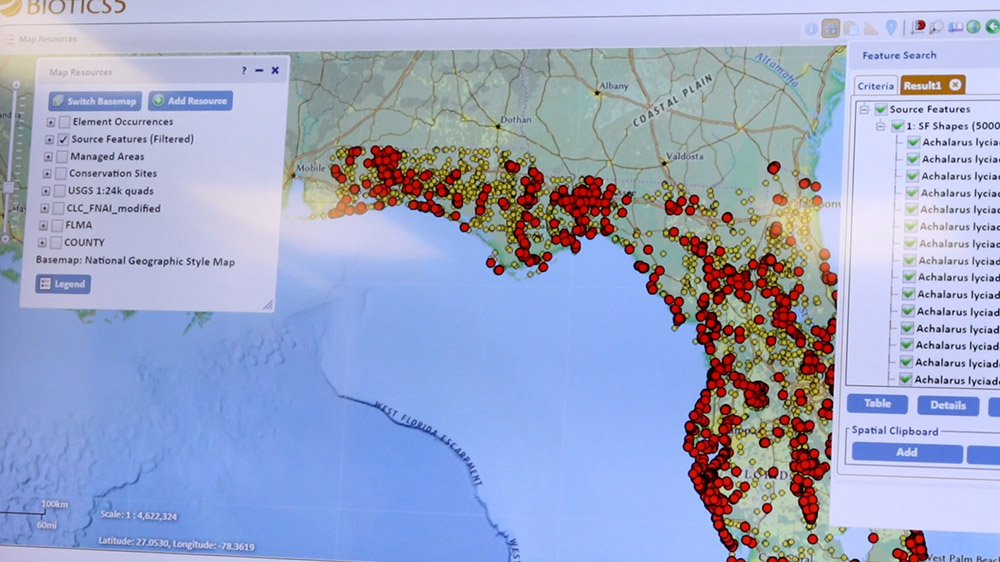

“This is all of our invert[ebrate] data,” says Mitchell East. With a keystroke, almost half of the dots start flashing red. “About 40% of our invert data comes from iNaturalist.”

Creating data points with iNaturalist

A few of those red points are bees I photographed in the Munson Sandhills. I found them while wandering the trails there with a camera, and keeping an eye on wildflowers in bloom. My camera is drawn to insects. Both in the yard and in the forest, if you pay attention to everything that flies or crawls, you will find that insects are endlessly diverse. Some are sleek and beautiful, some are bizarre. Sometimes the plain ones have the most interesting stories to tell, once you get to know them.

My primary way to get to know them is the iNaturalist app. I upload my photos, the app applies pattern recognition software, and it generates a list of recommendations based on what is likely for the area. Other users, often biologists, check my selection and either agree or make a different recommendation.

It helps teach me about the plants and animals I see, but it also creates a data point.

FNAI uses these data points to create ranks for each of the species it tracks. Florida Fish and Wildlife uses those ranks to help select species it might provide resources for conservation work. US Fish and Wildlfie also uses the data when they determine what species need federal protection.

All of our iNaturalist observations for a species, taken as a whole, could be the nudge it takes to restore a habitat or purchase land for conservation. That’s a lot of pressure on our photos, many of which we take rather casually on cell phones. I wonder, are all observations equally useful?

Sandhills cellophane bees at Leon Sinks?

Dave Almquist and I test this at Leon Sinks Geological Area, south of Tallahassee in the Apalachicola National Forest. A few years back, someone made two observations for sandhills cellophane bees here. The bees were taking nectar from blueberry bushes, which are in the same plant family as the plant with which they’re most associated. The photos weren’t close up, though, and so Dave wants to make an ID he can say is definitive.

Leon Sinks is known for its views into karst windows, rocky ponds exposed by the collapse of limestone caves. When you hit the trail from the parking area, you find those to the right, on the Sinkhole Trail. Head left, and you’re on the Gumswamp Trail. It’s a wetland area filled with gum and cypress trees. That’s promising. As the trail rises into the uplands, it circles back to the Sinkhole Trail, which passes through sandhill habitat. The sandhill habitat is filled with blueberry bushes.

Dave uses the location data from the posts to lead us to a blueberry bush, the blueberry bush where a cellophane bee was photographed four years earlier. The photos weren’t close up, and several cellophane bee species look similar at a glance. Dave wants a closer look.

“The iNaturalist records, to me, the pictures weren’t quite 100% saying that it was that species,” Dave says. “It was definitely the same genus or a relative of the bee that we’re looking for.”

When we get to the bush, there’s no cellophane bee. We wait around for a little bit and then head where we’d be more likely to regularly find the bees.

Sandhill balds – nesting sites of sandhills cellophane bees

Before my outing with Dave, I did a little exploring of my own at Leon Sinks. He had sent me photos of the bee, and its nests. Sandhills cellophane bees nest in open, sandy areas. Dave calls them “balds.” I wandered off trail near a couple sandhill spots where I found blueberries, and I found one with a few promising insect burrows.

I went on my scouting mission at the end of January, the earliest time of year I might see the bee. They specialize in the heath family, primarily climbing fetterbush (Pieris phillyreifolia), but are also known to visit blueberries. The peak bloom for these plants is late February through early April, which is when the sandhills cellophane bee flies. Many of our less common bees are specialists, and often on plants with a short seasonal window. This is an early flying bee, back in its nests by mid-April.

I bring Dave to this spot, and immediately, he finds the sand is too hard-packed.

“It doesn’t feel quite as soft, like beach sand or dune sand,” He says. Dave discovered the first known nesting sites for the bee and has a good sense for what we need to see. “The places I know of with the most burrows, they seem to be much more- it’s much more soft. Like if you walked in it, it would give under your feet.”

In the deeper, looser sand, the bee nests have a taller tumulous, or mound. These at Leon Sinks are too short, and the opening too narrow. We have struck out here, but Dave has a plan.

Using data to identify potential locations

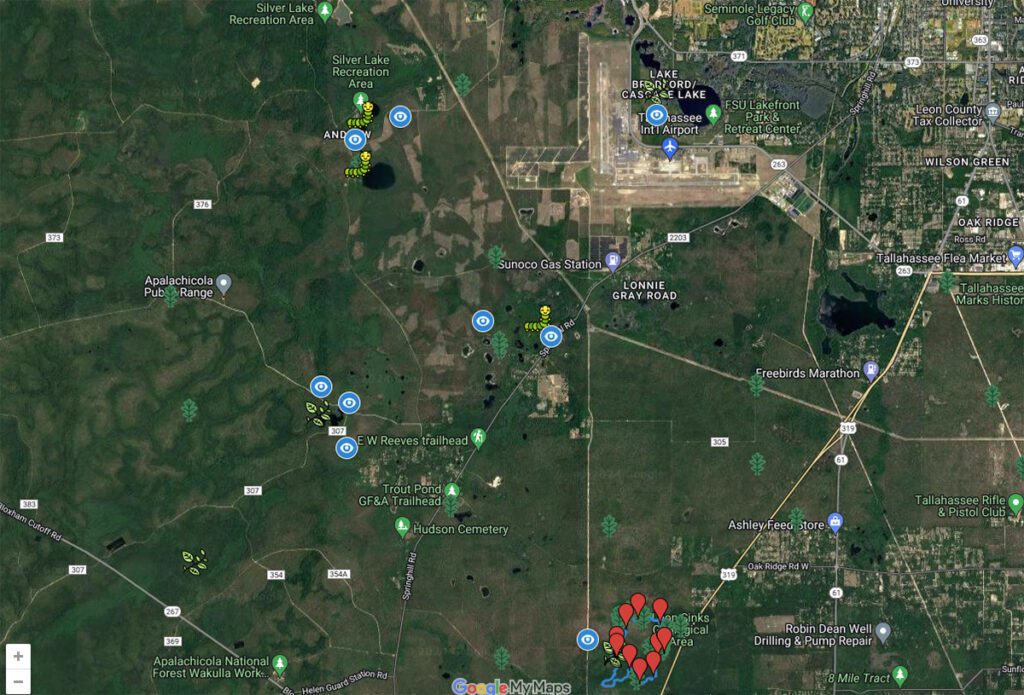

After our first outing, Dave sends me a map. My mission is taking shape. I now have several locations to check for the sandhills cellophane bee.

It’s a map powered by iNaturalist data. Since the bee specializes in climbing fetterbush, he starts with observations for that plant – there are only 13 in Leon County. For those unfamiliar with the plant, “it’s a strange blueberry relative vine that climbs up trees, burrows under their bark for support, and comes back out. But it’s not parasitic,” Dave says. The trees are often cypress trees.

The Okefenokee Zale moth (Zale perculta) uses climbing fetterbush as a larval host, so Dave factors in those observations as well. Only three in Leon County, but the moth is not likely to be far from where it will eventually lay its eggs.

Those observations help us find places where the sandhills cellophane bee might seek nectar. It nests in a sandhill ecosystem, and that is where we find turkey oak. Looking at observations for the three species in satellite view, he marked where one or more occurred around those bald, sandy spots.

I pick one of those spots and go.

Image quality matters

One spot is close to WFSU, and I rush out the first moment I can. I see rain in the forecast, and I don’t think I’d have much time. So I don’t bring my work camera. I’m treating this as a scouting mission.

Why would I ever go into nature without a camera?

I see a cellophane bee immediately and chase it down with my phone. I shoot some video and take a few photos. The bee looks similar to the rufous-backed cellophane bee, a common species that visits my yard in the late winter/ early spring. But how can I tell which is which?

“A lot of the pictures of insects don’t actually show the diagnostic characters,” Dave says of insect observations on iNaturalist. “If there’s not enough detail, you can’t really tell unless you can actually get a really good macro photo of some insects.”

In the case of the sandhills cellophane bee, the diagnostic characteristic is a long cheek, or malar space. You can kind of see it in this fuzzy cell phone pic, but it’s not definitive to my eyes.

There are also a few nesting mounds here, and these look right. I explore the area around the bald, and there’s a pond filled with cypress trees to the south of it, surrounded by blueberry bushes. I feel good about this place. I’m coming back.

The sandhills cellophane bee: Research Grade

I come back a second time and strike out, but that third visit has everything I need. Bees are active, and I am lucky enough to have one pause as it exits its nest. That’s my research-grade photo of the bee.

What is research grade, you may ask, and why does it matter?

When I make an identification for my iNaturalist observation, another user may agree or disagree with my pick. Or I may not be sure of a species, and select a genus or family, hoping that someone knows the species. There are many insects that will never be identified at the species level because they’re small and difficult to differentiate from each other.

If two-thirds of users agree on an identification, it’s research grade. Of course, I as a non-biologist can scroll through recently uploaded observations and make a series of ill-informed IDs. This is why the user community is the strength or weakness of the app. Since biologists may want to use the data in their research, many are curators on iNaturalist. They may not get to every observation made in our area, but when it comes to the rare, endemic, or imperiled flora and fauna, they are highly likely to take a closer look. If they see two people agree on what they see is a wrong ID, they will tag other biologists to get more eyes on the observation. There is occasionally a congenial debate.

We see the malar space of the bee in the photo, and I feel good about this ID.

Wandering the wetland, I also find climbing fetterbush that hasn’t been observed here yet. I upload some photos and move on to the next spot.

Which rare insect is next?

I strike out at a nearby site in the Apalachicola National Forest, where I wade through the deep sand of a dirt bike trail. Another site is inaccessible from public roads. I only find one new location, but using his map, Dave finds two more.

“Honestly, I’m surprised that it worked out as well as it did,” Dave says. “I expected to maybe find one new site, but not three of them in this short of an amount of time.”

We generated three new data points for FNAI, using data points from iNaturalist. On a native bee Facebook group, I exchanged comments with someone who found a couple sandhills cellophane bee sites in Mississippi. I also find a new iNaturalist observation further south into the Florida peninsula than it had been.

The sandhills cellophane bee has a wider range than we had thought before the spring of 2024. It’s not a continuous habitat, so it’s hard to say how many isolated populations there are between Tallahassee and Mississippi. Next March, if someone wanted to look, Dave’s map formula would work anywhere.

The formula could also work for other rare insects. Butterflies, like the frosted elfin, are never far from their caterpillar baby food plants. Rare insects are often rare because they have specific habitat needs, and are tied to plants that thrive in specialized settings. Instead of roaming aimlessly in the forest (which I’ll still do), I can target a species of interest and find myself in altogether new places.

I’m going to do this. If I’m successful, or unsuccessful in an adventurous or otherwise remarkable way, look for posts on my upcoming insect missions.