After crossing a ditch on a bridge of small logs, we wade through saw palmettos. Scattered under the slash pines around us are five trees with white bands painted on their trunks. “This is cluster number 64,” says Brian Camposano. “It’s one of the clusters of red-cockaded woodpeckers here on Tate’s Hell State Forest.”

Camposano is an Assistant Bureau Chief with the Florida Forest Service. We talk a little about the family structure of red-cockaded woodpeckers (RCWs), and the history of this land. He points out needlerush across the road from us, a coastal salt marsh habitat alongside RCWs.

Like many pine habitats in the Florida panhandle, this was once a commercial timber operation. But Florida didn’t purchase Tate’s Hell solely to restore fire dependent longleaf pine ecosystems. Nestled between Apalachicola Bay and the Apalachicola River delta, this land contains wetlands that feed into the bay’s imperiled estuary systems. Restoring hydrology is a top priority here.

Because they’re federally listed as Endangered, protecting red cockaded woodpeckers is also a priority here and on lands throughout the southeast. Camposano says the two goals aren’t at odds. He says the FFS has “a holistic approach to to forest management, not prioritizing any one thing over, you know, anything else.”

As Camposano explains it, this approach means that even if the FFS didn’t have to focus on helping this one bird species, its management of the forest would still benefit it.

The Proposal to Downlist the Red-Cockaded Woodpecker

In 2020, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed downlisting red-cockaded woodpeckers from Endangered to Threatened. It touted a large increase in RCWs across their range.

“Sometimes it seems once an animal gets on the Endangered Species list, you never see them come off – that is why it is so important to highlight a success story like this one,” said then Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue in a release announcing the proposal.

The red-cockaded woodpecker first received Endangered status in 1970, under the law preceding the Endangered Species Act. At the time, there were between 1,500 and 3,500 RCW clusters- less than 10,000 individuals. Today, there are about 7,794 clusters, and about 15,000 individuals. The reason for the increase? The use of artificial nesting cavities.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers are the only North American woodpecker to make nesting cavities in living trees. Other woodpeckers nest in the soft wood of dead, standing trees. RCWs specialize in living pines with soft heart wood.

The soft heart wood comes courtesy of heart pine disease, Porodaedalea pini. It doesn’t kill the trees, but it makes it so that an RCW can peck out a cavity. Porodaedalea pini affects the RCW’s nesting pines- loblolly, shortleaf, and the bird’s preferred longleaf- starting at 60 years of age. Due to extensive logging in the twentieth century, trees of that age are in short supply for the time being.

“There’s no way to accelerate a tree’s age,” says Camposano. “If I need a 60 year old longleaf pine tree to have heart rot in the middle of it so they can start excavating a cavity, I can’t accelerate that timeline. So the only thing I can do, is I can try to cut an insert box into a tree.”

Can Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers Survive Without Humans?

Artificial nesting cavities have made it so that red cockaded woodpeckers can nest and increase their populations. But is their success over the last few decades enough to declare a victory for them? Critics say no.

“One of the key elements for finally declaring recovery is the lack of reliance on artificial cavities.” Says Ramona McGee, a lawyer for the Southern Environmental Law Center. She and the SELC have been petitioning to keep the RCW’s Endangered status.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service has recently revised their initial proposal. It has added species specific protections to the RCW’s proposed Threatened status. In many ways, it will be as protected as it currently. But McGee says that until the bird can break its reliance on humans, downlisting is premature.

“Red-cockaded woodpeckers are in an interesting category because they depend on these 60, 70, 80 year old trees,” says McGee. “So we need to be planting now… really 30 years ago planting these trees for these red cockaded woodpeckers to migrate into eventually with warming temperatures.”

Climate Change, Storms, and Resiliency

Warmer water surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico have produced an increase in Category 4 and 5 hurricanes over the last couple of decades. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, 63 of the 124 current RCW populations “are vulnerable to potential catastrophic impacts of hurricanes, particularly major hurricanes.” This includes all Florida populations, like the one in Tate’s Hell.

“If Hurricane Michael had shifted east,” says Brian Camposano, “you know, going into the 20 to 25 mile range, I mean, we could have had a major loss on this part of the forest.” Michael did affect RCW clusters to the north, in the Apalachicola National Forest.

The RCWs in Tate’s Hell are a part of a larger population in the adjacent Apalachicola National Forest and St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge. This is, in fact, the largest population in the bird’s range, with 858 clusters. Fifty six of the sixty three populations vulnerable to major hurricanes are considered “low or very low resiliency.” This one, however, is the most resilient.

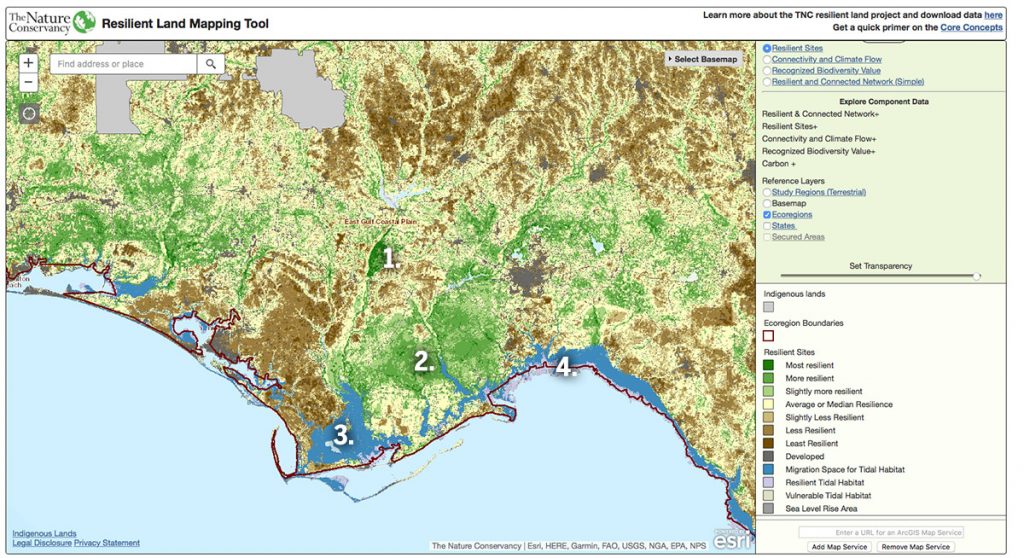

The image above is from The Nature Conservancy’s Resilient Land Mapping Tool. It grades climate resiliency. The large expanse of the Apalachicola National Forest (area labeled 2) is color coded in green- slightly to more resilient. At almost 600,000 acres, it’s a large chunk of forest land.

The RCW population here is large, and it has a lot of contiguous habitat to use. A direct hit from a hurricane anywhere in this area would be catastrophic locally, but the overall population would more likely persist and rebound.

This is not the case for most red cockaded woodpeckers. Of the 124 populations recognized by the USFWS, 108 are small “with inherently very low or low resiliency.”

RCWs on Military Bases

“So on the whole, the proposed rule is certainly an improvement from what was proposed back in 2020.” says Ramona McGee. “However, this still is a proposal to downlist. This still is a move to remove some protections and remove that endangered status that is unwarranted by the science and by the law.”

One place where RCWs would be less protected is military bases. Fourteen populations reside on bases such as Eglin Air Force Base and Fort Benning.

“We manage the land on Fort Benning as if it was our own,” said Fort Benning’s Major General Patrick J. Donahoe at a ceremony announcing the 2020 downlisting proposal. “We truly know it is America’s.

“Since the 1980s, Fort Benning has been one of the hubs for the red-cockaded woodpecker conservation efforts nationwide” Donahoe added. He went on to say that it “doesn’t come cheap”, costing the base one million dollars a year.

While military bases would continue to manage habitats if the RCW were downlisted, they would in certain instances be allowed “incidental take” of woodpeckers. Take is a term in the Endangered Species act that means “harm, harass, or kill.”

“Military installations could harm, harass, or kill red-cockaded woodpeckers if it was in accordance with one of their integrated natural resource management plans,” says McGee. “And the military installations could take those woodpeckers in relation to military training activities, as well as habitat management activities. So there’s still some wiggle room there for the military to harm and kill red-cockaded woodpeckers.”

Will Relaxing Rules Help RCWs?

Brian Camposano sees the relaxing of rules concerning incidental take as a good thing for the species in the long term. Current rules prohibit incidental take when managing the bird’s habitat.

“Presuming that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does move ahead with downlisting to Threatened, [there] will be a rule that comes out that that basically gives us a little bit more flexibility on some of the things that we can do in the in the ecosystem to to help the species move along. And some of that will be relevant here… [in] the next several decades, some of these slash pines, you know, approach the end of their life. They’re a much shorter lived tree species than longleaf pine.”

If artificial nesting cavity trees die, the Forest Service would have to relocate the nests to new trees. Camposano says they can do this without “jumping through as many hoops” under the new proposed rule.

Regardless of any rule changes concerning red-cockaded woodpeckers, Camposano says the Florida Forest Service will not change the way it manages forests.

“We don’t see a real change in how we’re going to do anything because we’ve been managing the way we’ve been managing for a long time now. It has benefited The RCW as we’ve grown all of our populations over time, and we’re at a place now where we’re happy with our progress. You know, obviously the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is happy with the progress overall throughout the range and and it might be time to take that next step to downlist them to Threatened.”

Reopened Comment Period

With every proposed rule change, the US Fish and Wildlife Service requests comments from the public. They are asking, specifically, for people to share comments that help them make a decision based on the “best scientific and commercial data. From their page:

If you have already commented on the proposal to reclassify the RCW, then you do not need to resubmit those comments. However, since changes have been made to the proposed 4(d) rule, interested parties are encouraged to review the rule and submit comments accordingly. Any final action resulting from this proposed rule will be based on the best scientific and commercial data. Please note that submissions merely stating support for, or opposition to, the action under consideration without providing supporting information, although noted, will not be considered in making a determination.

Red-Cockaded Woodpecker in Images

Banding an RCW Chick

In May of 2015, we watched Tall Timbers’ Stoddard Bird Lab Director, Jim Cox, band a newly hatched RCW. Each banded bird receives a unique color combination, and is registered in a national database. As birds fledge and move out on their own, land managers can track their movement. This includes woodpeckers relocated to bolster small populations.

Brian Camposano points out that there’s always a danger when handling an Endangered species. To receive a permit to band wild birds, a person “must be able to show that they are qualified to safely trap, handle, and band the birds.”

Because only a highly trained person can band a bird, Jim Cox says that “there’s a very low rate of incidents, something bad happening… you always have to weigh that with the information you’re getting out of what you’re doing.” In other words, does the potential to help the species with new information outweigh the potential harm to the individual bird?

Feeding an RCW Chick

As soon as Jim Cox ascended his ladder, we could hear multiple RCWs chirping. It was an understandably traumatic experience for the family group, which includes parents and one to four older male children. Red-cockaded woodpecker females usually leave their cluster to find a breeding partner after fledging. Males, on the other hand, will either leave or stay to help raise future siblings.

This may be due to the length of time it takes to create a cavity. Even in soft heart wood, it can take years to RCWs to finish one, and families may have as many as twenty cavities in a cluster. Each individual in the group has its own cavity, and the male’s cavity houses the nest. Male children that stay may one day inherit the cavities.

The woodpeckers also peck resin wells into trees with active cavities. The waxy buildup you see in the image above is tree sap released by RCWs. This makes it harder for rat snakes and other predators to climb the tree.

As soon as Cox returned the hatchling, three different RCWs made their way to the trees around the nest. After about fifteen minutes, the woodpecker above flew to the cavity with what looks like a spider.

A Keystone Species

A few years ago, I was walking in the Munson Sandhills with a camera when I approached a cluster of banded trees. It was April, and I heard peeping from one of the artificial RCW cavities. I was hopeful. It was around the time of year when RCWs nest.

Instead, an entirely different bird flew up with something in its beak, and deposited it in the nest. Here was a different story.

On the ground in this same habitat, gopher tortoises dig burrows used by hundreds of other animal species for shelter. Red-cockaded woodpecker cavities don’t host quite that many, but their cavities are an important for many birds. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, wood ducks and “southern flying squirrels, redbellied woodpeckers, redheaded woodpeckers, eastern bluebirds, brown-headed nuthatches, tufted titmice and great crested flycatchers” are some species that can take over RCW cavities, among others.

Here we see a great crested flycatcher.

At the cluster we visited in Tate’s Hell, I noticed a woodpecker-made cavity on a tree with another, artificial cavity. Camposano noted that the cavity had been enlarged by another bird species. This makes it unusable by red-cockaded woodpeckers, which are fairly small.

Excavating a New Cavity

A few months after seeing a flycatcher using an RCW nest, I returned to that spot in the forest. This time I heard woodpecker chirps. Two woodpeckers flew to a tree next to a banded tree, and I caught this one in the process of creating a cavity. I was out testing a new dslr camera, but we hadn’t yet received the zoom lens. It would he been nice to zoom in closer, but still, this was a cool thing to encounter walking in the woods one day.