It’s no secret; we love our beaches. Floridians across the state take pride in our gorgeous coastline, and visitors from across the world travel to enjoy the sunshine state’s beaches. On the Forgotten Coast, St. George Island is a jewel, adored by locals and visitors alike. For some, this love is couched in a deep understanding of the ecology of barrier islands. Investigating how they grow and change, how they respond to hurricanes, and how they may respond to changing climate conditions – including sea-level rise and stronger hurricanes.

Dr. Tom Miller, a professor at Florida State University, is one of these people. Since 1999, Dr. Miller has conducted an annual census of the plant communities at St. George Island State Park to understand how the island changes over time. Through his work, Dr. Miller has seen how the island responds to devastating storms, which plants may be the best for restoration, and how tiny changes in elevation can lead to significant changes in the habitat.

The Three Habitats of a Beach Dune System

Just across Apalachicola Bay lies the long and narrow St. George Island. A popular destination for tourists, birders, and beachgoers, the island brings visitors from across the county. Many of these visitors find their way into St. George Island State Park to take in the soft white sands and blue-green waters. A beachgoer often interacts with one of the three habitat types on their way to the water, the foredune.

Foredunes are the first line of dunes running parallel to the ocean; they’re characterized by the ever-lovely sea oats (Uniola paniculata) that top the ridges and beach morning glory (Ipomoea imperati) that winds its way down dune tops and onto the beach.

Going behind the foredunes, you enter the wet interdunes. These low-lying areas often fill with fresh water during the wet times of the year and hold onto water in the soils. Wetland plants are easy to find here; species like cattails (Typha) and marsh grass (Spartina) abound, along with treefrogs, wetland birds, and a variety of different snake species.

After wading through the wet interdune, you enter into the last habitat on the island before reaching the bay, the backdune. This is the oldest habitat on the island, plants have had time to establish, and the conditions aren’t as harsh as in the foredune and interdune. The backdune supports longer-lived species, like pine and oak trees, and shrubby plants like wax myrtle and groundsel. The backdune is also a great place to spot cactus, rattlesnakes, and birds of prey (like eagles and harriers) hunting for their prey.

Digging into the Data- How do St. George Island Dunes Respond to Hurricanes?

Understanding how these habitats change over time has been a research goal of the Miller Lab for the past 22 years. In addition to investigating the ecology of the ecosystems to better understand how barrier islands grow and change, collecting these data is also critical for understanding the effects that anthropogenic and natural disasters have on our coastlines. “We have very little background information, particularly in the Gulf of Mexico, about natural ecosystems.” Dr. Miller says while sitting next to one of his foredune plots, “so, then when you have something like an oil spill occur, or you have a major drought occur, or you have climate change – a much slower, going phenomenon – you don’t know what’s changing.”

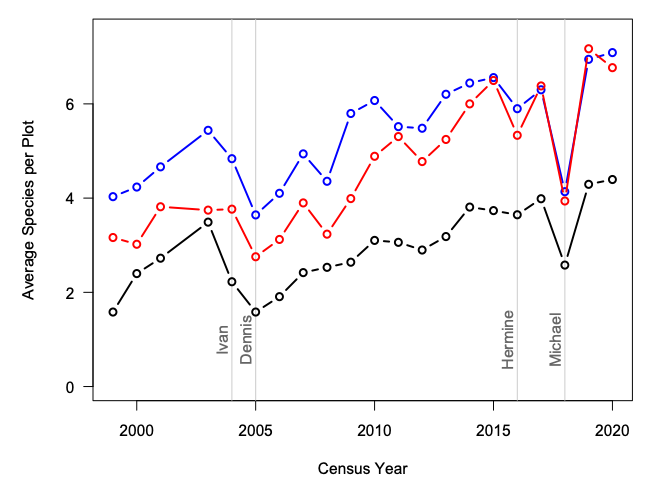

With the long-term data collected during the annual census, Dr. Miller has established a baseline of what the plant communities look like on the dunes and can better understand the effects of large-scale disturbances. This baseline data has been beneficial for understanding the impacts of hurricanes on species diversity on the dunes. The graph above shows us the average number of species per plot for 1999 – 2020, with major hurricanes marked on the year they occur. Looking closely, we can see a general trend – hurricanes cause a drop in biodiversity on the plots.

This is often due to a loss of sensitive species that are salt intolerant and don’t survive the overwash. We can also see that the dunes rebound from storms reasonably quickly in some cases, either with a gradual increase in biodiversity after hurricane Dennis or a more dramatic increase as with the years following Michael. From the census data and a strong understanding of baseline conditions, Dr. Miller has proposed which species may be best for restoring dunes after a significant disturbance.

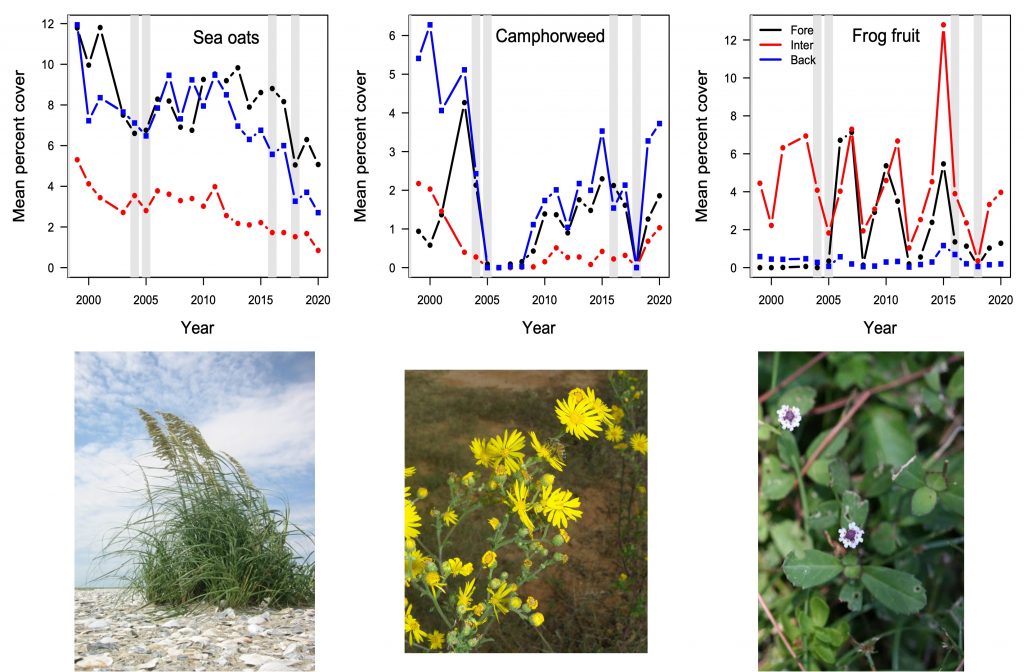

Not all species respond to disturbance the same. With detailed data on the species level, we can gather insight on how each species responds to storms and how they may be similar or different from one another. The graph above shows the average percent cover from 1999 – 2020 for three common species (Sea oats, Camphorweed, and Frog Fruit) with major hurricanes marked by grey bars.

How do Different Plant Species Respond?

Some species, like Camphorweed, are entirely wiped out by hurricanes – driven to near extinction on the plots when the hurricanes bring a large storm surge. Others, like Sea oats, don’t respond very strongly- as they’re more salt-tolerant- but will decline during strong storms. Then, there’s Frog fruit – an odd plant that seems to do whatever it wants. Many questions are still unanswered about the lives of the plants that live out on the dunes. The census data contains a wealth of information, with plenty of stories still to tell.

Future Directions

Now, the Miller lab has set their sights on understanding how the plants get the nutrients they need to grow and establish themselves. Our Gulf beaches are famous for their soft, white sand – but soft white sand is nearly devoid of nutrients, so where are plants getting their nutrients?

This is a crucial question to understand since the plants build the dunes that protect our coastlines – so healthy plants mean healthy dunes and more resilient coastlines. Understanding nutrient input is a work in progress, but the Miller lab suspects that seaweed may have something to do with it. This is where my own work comes in. Seaweed may act like a fertilizer for dune plants, much like decaying leaves in a forest, or compost added to your garden. I’ll be carrying out a series of experiments in 2022 to test this using a stable isotope tracing study to see how our primary foredune species (Sea oats, Coastal Searocket, and Beach Morning-glory) use the nutrients given off by seaweed as it decays. More on this another time.

And finally, a trip to St. George wouldn’t be complete without saying a quick hello to the shorebirds and other creatures that roam the island. Want to see this incredible ecosystem for yourself? St. George Island State Park is a gorgeous 2 hour drive from Tallahassee, and is well worth the trip!