In our last visit to Torreya State Park, we saw a park whose unique tree canopy had been seriously damaged by Hurricane Michael. Today, we see how, in another section of the park, they’ve planted over 1.6 million longleaf pine in an effort to restore sandhill communities surrounding steephead ravines.

For those of you who’ve visited Torreya State Park, I’ll ask you to remember the drive in. You pass a lot of picturesque rural landscapes, and forest land. It helps set the mood for your remote nature experience in the bluffs overlooking the Apalachicola River. But then, closer to the park, you pass an unsightly expanse of bare earth or two. It’s a momentary break in the scenery. In a few years, though, it might very well be the highlight of the drive.

In fact, some of those bare patches are starting to grow in.

“As you drive in, you’re passing much of our lands.” says Jason Vickery, the park’s manager. “Those open fields of, you know, wiregrass, and little longleaf pines coming up- that’s all efforts you’re seeing that started in the early 2000s.”

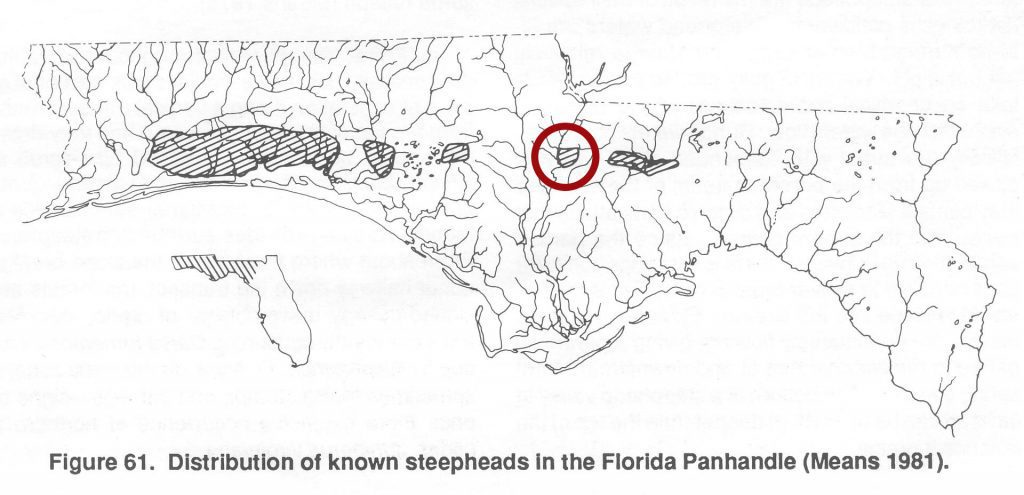

The Florida Park Service purchased the Sweetwater Creek tract in the early 2000s. Their goal with the purchase was to protect the steephead ravine for which the tract is named (and which we visited in 2017). Steepheads are lucky in that it’s impossible to move heavy machines in and clearcut them. So their unique ecology remains intact.

The problem was the area around the steephead. About 4,600 acres of the roughly 7,000 acre tract had been industrial timber land. It was covered with the wrong kind of pine for a sandhill habitat, and much too thickly to support the fire needed for native flora and fauna to thrive here.

Clearcutting is the first step in restoring the native longleaf pine/ wiregrass habitat. It’s a process that, in its entirety, will take hundreds of years. But it’s also a process that produces visible and satisfying results within just a few years. No one reading this will likely see the end result, but we can easily see how it’s taking shape.

Four Scenes of Sandhill Restoration

The park has sectioned off the tract into Restoration Zones of about 300 acres each, systematically working through them. Some are several years in, and some have yet to be touched. It gives us several snapshots of the process.

I spend a day following park biologist Mark Ludlow from one site to another, seeing several years of work unfold in a few hours.

1. The Sand Pine Plantation

This is a dark, shady place, thick with trees. The ground is covered with pine needles, tufts of reindeer moss, and not much else.

“This is sand pine (Pinus clausa), which is native to Florida, but does not naturally occur in a sandhill habitat.” Mark says. “The establishment of this plantation eliminated most of the native ground cover. You’ll see that there isn’t any wiregrass to speak of.”

Sandhills are high, dry places. Because sand does not hold water, rain percolates down through the sand until it hits a hard layer of rock or clay. In the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region, as The Nature Conservancy’s Chaz Oliver tells us, that could be 170 feet below the surface. There, water collects in surficial aquifers, the sources of steephead ravines.

The dry surface above is a landscape shaped by fire. Fire resistant longleaf pine trees (Pinus palustris) grow a comfortable distance from each other, creating a lot of sunny space for ground cover plants to grow. The most important of these is wiregrass (Aristida stricta), a plant that needs fire to seed, but that also provides valuable fuel to spread fire.

Wiregrass is one of hundreds of plant species that cover the ground in sandhill habitats. Those plants, in turn, support a diversity of animal species. It’s a far cry from the shaded, barren ground where we’re standing now.

2. The Clearcut Forest

From a place with too much tree cover, we go to a place with none.

“Doesn’t look like much.” Mark says “But this is what’s necessary to restore the site from a sand pine plantation back to a sandhill.”

Heavy machinery has removed everything but the stumps (that would be too expensive) and an odd hardwood tree here or there. “The cleaner, the better, because it needs to be replanted using farm tractors.”

Bradley Keegan and Jessica Larimer drive the tractors across the emptiness, dropping wiregrass seeds along the way. Bradley and Jessica are Conservation Stewards with The Nature Conservancy in North Florida. TNC’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve is Torreya’s neighbor to the south, and TNC is a leading partner in this effort. Along with their other partners, they’re restoring critical habitat in one of the nation’s top biodiversity hotspots.

You’ll notice that they’re planting wiregrass before the longleaf. Establishing the understory is critical.

“It’s where the majority of the diversity is,” Chaz Oliver says, “it’s the habitat that all the species use to make this system what it really is when we think of the iconic longleaf pine/ wiregrass system, is this groundcover that’s really the bread and butter of it.”

3. The Young Forest

In Restoration Zone Seven, we see the progress that can be made in a few short years. Wiregrass is everywhere, and the longleaf is just a little bit taller than it is. Walking into the wiregrass, we can see a few different plants have made their way back into the sandhill. Little yellow flowers called pineland silkgrass (Pityopsis aspera) are among the only flowers not yet gone to seed in early December, along with a little bit of goldenrod.

We also find plants common in well drained, sandy soils, prickly pears and common yucca (Yucca filementosa).

Here, Mark shows us how fire orders the sandhill plant community.

“This zone was just burned a few months ago in July.” He says. “You can see how the wiregrass has flowered and produced seed.” He runs his fingers over the seeds, collecting them in his hand. They’re like short, thin hairs. “And the fire is essential to cause the wiregrass to flower and produce seed.”

Wiregrass also benefits from fire’s effects on other plants, especially hardwoods like turkey and laurel oaks. Mark notes fire’s pruning effect on one particular laurel oak. It stands chest high, black and leafless. New, green leaves grow out from its base, so it’s still alive. But it will stay a shrub, and as a shrub it does have an ecological role to play in this ecosystem. Without a burn every two to three years, oaks become better established. This makes them harder to kill with fire, and they will start crowding out groundcover species.

4. The Mature Sandhill Habitat

I use the word “mature” loosely here. A truly mature longleaf ecosystem is thousands of years old. The majority of existing longleaf forest is second growth, planted by humans on cleared land. The “mature” forest where Mark takes us is on the original park property, right by the front gate.

“These properties were originally acquired for the park in the 1930s. They at least date back that far.” He says. “And some of this land had been turned to agriculture when it was acquired in the 1930s. This is probably one of those tracts where we’re looking at almost 100 year old longleaf pine.”

This tract has been burned regularly for about half that time, since the 1970s.

As you see in the video, it has grown trees and a full, diverse understory. I didn’t have to walk far to find a gopher tortoise burrow. And the trees are around the right age to get red heart disease, which softens the heart pine enough for red cockaded woodpeckers to build their nests in them.

Within our lifetimes, we may see the restoration zones look something like this. As Chaz Oliver explains, you start with a handful of plant species- longleaf pine, wiregrass, pineywoods dropseed, broomsedge, and a few others. Then, you burn every two to three years. Nature takes care of the rest.

“We kind of restore the foundation.” He says. “And then over time fire, and just the natural processes in the system, kind of starts to bring back the remaining diversity. Once we sort of build the house, it takes hundreds, if not thousands of years to really see what a lot of people call pre-Columbian conditions.”

4a. The Old Growth Forest

Pre-Columbian, as in before Europeans. We have few forests in our area that have never been cut, that have remained intact for thousands of years. The shot I used at 4:59 in the video is of an old growth longleaf habitat in Thomasville. This is a red clay upland forest. It’s a similar ecosystem to sandhill, but red clay is much less permeable than sand; where sand drains, clay holds water. There’s a wide overlap in groundcover species, but also a few key differences. Upland pine forests lack prickly pears and turkey oaks, where sandhill doesn’t have flowering dogwoods or other plants adapted to wetter soils.

Anyhow, the footage I have of these rare, old growth longleaf habitats are from the Red Hills. You may notice the size of the trees. A longleaf pine that is hundreds of years old is noticeably thicker than much of what we see in the Apalachicola National Forest or in the Bluffs and Ravines region. Getting the 1.6 million (and counting!) newly planted longleaf to this size is a multi-generational endeavor.

“Well, I would say between 40 to 50 years it’s going to start looking pretty natural.” says Mark Ludlow. “The longleaf will get taller. But it’s going to take 100 years or more to look like it did with the mature longleaf. Hopefully our grandchildren will appreciate it.”

The Ancient Sand Dunes of the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines

Chaz had a few interesting things to say about this area that I didn’t get to include in the video. I mentioned earlier how he said the sand here can run 170 feet deep. To reiterate, water drains right down to the rock or hard clay 170 feet down, forming “underground lakes.” It’s a geology tied to a coastline millions of years gone.

“Right here in the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, this ancient sand dune, as it is, really holds a plethora of unique species.” When searching for Apalachicola dusky salamanders in Sweetwater Creek, Bruce Means pointed out how steephead ravines in Florida formed more or less a straight line along an ancient coastline. He figured these were likely barrier islands. Think of the dune habitat we have today on the barrier islands enclosing Apalachicola Bay; a few million years ago these were a few dozen miles upriver.

Today, sea level is lower than it was three million years ago or so, and these islands are now high river bluffs. As the bluffs erode over time, the surficial aquifers within them are exposed, and begin to seep into the river. Over thousands of years, a seep will dig into a bluff, creating a steephead ravine. It’s a geological phenomenon that only occurs in Florida.

I went into the unique biology found in steepheads in our last Torreya post, and I don’t want to be repetitive. In short, plants and animals of northern origin inhabited steepheads during the ice ages, and due to the unique geology of these ravines, these species stayed after the Pleistocene and in many cases evolved into new species seen nowhere outside of the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region.

We saw one such plant at the edge of a steephead with Mark, Apalachicola rosemary (Conradina glabra). In December, the plants we saw still had a flower or two.

Apalachicola Rosemary is endemic to Liberty County, and grows at the edge of steephead ravines. Where we saw it, the steephead was surrounded by sand pine. In the future, the unique flora and fauna in the ravine will be surrounded by a highly diverse habitat, which should only enhance it.

A Quick Note About Some of the Animals in the Video

I’ve already identified some of the plants in the sections above. I wish I had a better ability to identify the many wildflowers we saw after they’d gone to seed. Anyhow, I showed a few animals typical of this environment, and I thought I’d share what they were and where I filmed them all.

02:20 Gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) at Birdsong Nature Center. Another Red Hills location, so I picked a closeup where we could only see the tortoise for the video.

02:21 Red cockaded woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis) at the edge of an ephemeral wetland in the Munson Sandhills. I recorded it after a striped newt release by the Coastal Plains Institute in early 2019.

02:23 Frosted elfin (Callophrys irus) in the Munson Sandhills. This is a butterfly that depends on fire. Its larval food is the sundial lupine (Lupinis perennis), a groundcover plant that would get crowded out by hardwoods without regular fire. A nitrogen fixer, this plant enhances nutrient poor sandy soils.

02:24 Brown-headed nuthatch (Sitta pusilla). I actually saw this right near where I recorded the woodpecker. We were shooting footage on EcoCitizen Day, and Tall Timbers ornithologist Rob Meyer pointed them out and talked to us about their nesting habits. Brown-headed nuthatches, Bachman’s sparrows, and red cockaded woodpeckers are the three bird species found only in longleaf ecosystems.