Perhaps no swamp tree captures the imagination more than the ogeechee tupelo. But altered river flows on the Apalachicola River are causing a decline of this critical plant in the river floodplain.

Subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Blog to receive more videos and articles about our local, natural areas, and subscribe to the WFSU Ecology Youtube Channel

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

I have to state, for the record, that it was Georgia’s idea to do a segment where she learns to drive the Riverkeeper boat. Georgia Ackerman is one of the most experienced people I know out on the water. In a kayak. But as the new Apalachicola Riverkeeper, she needs to drive the boat.

I wanted to cover the transition between herself and Dan Tonsmeire, and I had two requests. First, take me (and the WFSU viewers) somewhere we’d never seen before. Second, I wanted some last nuggets of wisdom from Dan, as he handed the reigns to his successor.

To Georgia, that meant a segment where she, with Dan’s guidance, gets used to driving the boat. In narrow sloughs, and between tupelo trees in swamps.

These are critical places to the Apalachicola River and Bay system. As Dan says in the video, the river is 106.5 miles long. But when you factor in the sloughs and creeks spreading out from the river and into the floodplain, there are over 400 miles of waterways. The dominant habitat within these additional 300 miles is the tupelo/ cypress swamp.

I keep returning to this habitat. With 300 miles of channels, there’s a lot to explore. Two years ago, Dan, Georgia, and the RiverTrek team guided us through Tate’s Hell. We kayaked and boated swamps, and the many water ways issuing from them in the Apalachicola River delta. We looked at the connection between Tate’s Hell and the bay: oysters are fed from decomposing muck in swamps all along the river.

Today, we take a closer look at that muck. And we’ll look at the leaves that make a lot of the muck, those of tupelo trees. Tupelos and other swamp trees are disappearing from the Apalachicola floodplain, and this has implications for both the honey and seafood industries.

Dan Tonsmeire and Georgia Ackerman, against a large bald cypress tree. In January, Dan handed Georgia the reigns as she became the Apalachicola RIverkeeper.

The Quintessential Tupelo Swamp

“We’re in the dark and mysterious swamp.” Dan says. “The backwater swamp!”

“The quintessential backwater swamp,” Georgia teases. He snarls at her. I had to laugh, because Dan’s taken me to a few “quintessential tupelo swamps,” as he likes to call them, over the years.

One is Owl Creek, in the Apalachicola National Forest, about twenty two miles from Apalachicola Bay. It’s great for boating, or kayaking- I’ve paddled it several times for Riverkeeper related projects, a few times with my son Max.

Another is Sutton Lake, just south of Bristol (and about 60 miles north of Owl Creek). It’s full of old growth cypress and tupelo trees that escaped logging because their large trunks were hollow. Unlike Owl Creek, you can only get there when the water’s high enough, and even then, it’s a little bit of a squeeze.

Today, we’re heading to Outside Lake.

Outside Lake is just north of Estiffanulga Bluff, which sits at mile marker 63 on the river (the markers count down from 106 at the Woodruff Dam, to 0 at the John Gorrie Bridge in Apalachicola).

The trek into the lake makes a nice driving test. Water bulges out of the main river channel and into the floodplain in kind of a sloppy way. People have categorized these waterways as sloughs, creeks, lakes, etc., but in a lot of places, there’s no defined path. It’s just a mess of water and trees. This is where we’re making Georgia drive us. It gets maze-like, and we have to watch our heads as branches close in.

Eventually, it opens up. We circle ogeechee tupelo trees free standing in the water, full of buds about to bloom.

I have done a story on tupelo honey. Tupelo honey is a premium product, and an important part of the river economy. In this regard, I think, people understand the value of this plant. What we’ll see today is its value beyond its sweet flowers.

The Lifeblood of the Apalachicola River and Bay System

Dan wants to show us some large cypress trees, so we get off the boat, sidestepping a copious amount of poison ivy along the bank. We hike to a spot where we find a tall, thick trunked cypress tree. All around it are crawfish chimneys. These little freshwater crustaceans build something akin to an ant pile out of the clayey swamp muck.

Dan picks up some of this muck and squeezes it into a squishy ball.

“It’s like mud, it’s gooshy. It’s not sandy,” He says. “And that is what the consistency of most of the floodplain is, is that kind of clay, gooshy stuff.”

Crawfish and other animals live in this muck, and contribute to its consistency. “Worms and [other species] that are living in the soil, like the crawfish, kind of condition the soil. They are what keeps the soil porous and loosen it up.”

Tupelo trees, unlike cypress, are deciduous. I have a fondness for kayaking in tupelo swamps in the winter, when their leafless trunks appear skeletal as the canopy closes in around you. The two dominant species of tupelo in the floodplain, water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) and ogeechee tupelo (Nyssa ogeche), drop the most leaves here.

Helen Light and Melanie Darst highlighted the importance of leaf litter in their 2008 USGS study on the Apalachicola’s drying floodplain forests. Fallen leaves are shelter for insects, which feed birds, and, when the river rises, feed fish as well. The leaves then decompose and add organic material to the soil.

Not every backwater area is connected to the river year round. However, when the Apalachicola floods, the system is fully connected, and the nutrients in that soil make their way down to Apalachicola Bay, where they feed the bottom of the food web.

It’s a beautiful system. Crawfish and tupelo trees help feed oysters and shrimp. Of course, the Apalachicola oyster is in year six of a fishery collapse that doesn’t look to recover soon. The river’s other icon is also in decline. But where the oyster fishery’s demise came suddenly during a drought event, altered river flows are causing a more gradual decline for the ogeechee tupelo.

The Thinning of the Floodplain Forest

Near the giant cypress tree is an ogeechee of similar size, toppled over. Dan uses this to illustrate what is happening in the Apalachicola floodplain. “This is an older tree,” He says. “And you can see it’s breaking down, falling down. So the older trees are dying out. But there’s no real young tupelo coming in.”

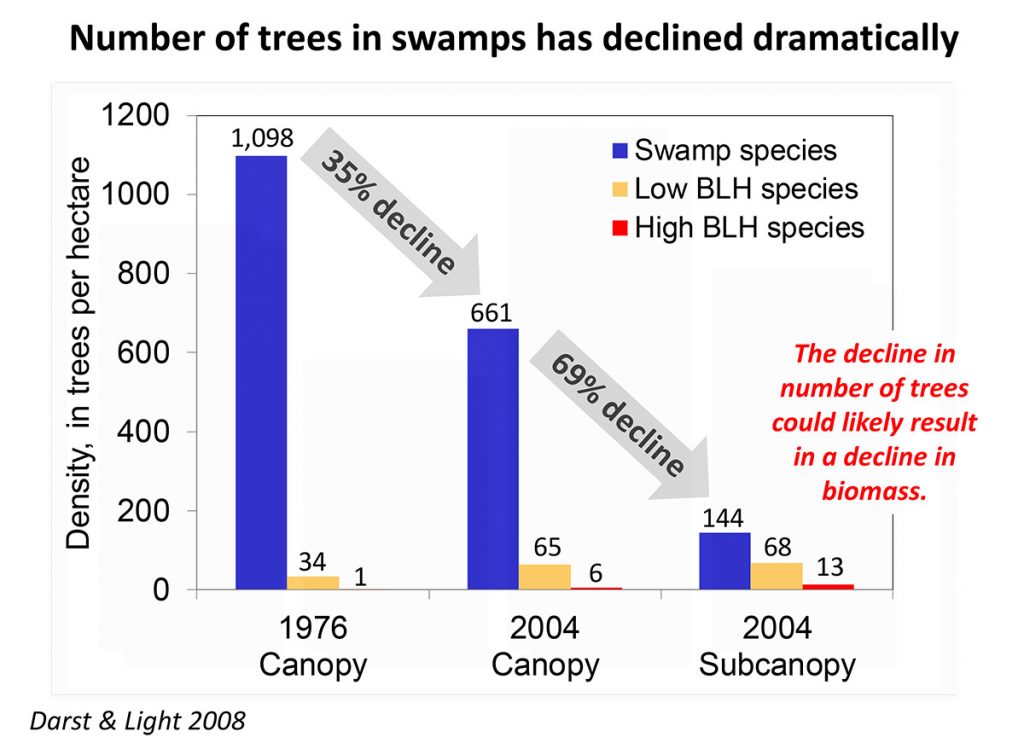

Between 1976 and 2004, Helen Light and Melanie Darst surveyed trees in the Apalachicola floodplain for the US Geological Survey (the study linked above). by 2004, they estimated that were 4.3 million fewer trees in the floodplain canopy, a loss of 17% (Page 53). Of that, 3.3 million were swamp species, those that thrive in the wettest conditions. They estimated a loss of “at least 19 percent for water tupelo, 38 percent for popash, and 44 percent for Ogeechee tupelo.” (53)

The cause is a drying floodplain. In a separate study that Light, Darst, and others completed for the USGS, they explored the effects of water level decline on the floodplain. Notice that they’re looking at water level, and not discharge from the Jim Woodruff Dam in Chattahoochee. According to the study, the average amount of water that flows through Chattahoochee is roughly the same as before the dam was built:

“Average discharge in the earliest 30 years (1929–1958) and latest 30 years (1975–2004) in the period of record at the Chattahoochee gage was very similar (21,200 and 21,500 ft3/s, respectively)…” (Page 41)

Despite the similar overall water flow, they found that in the last ten years of their study period, one of their study swamps was inundated 29% of the time. The output was more or less the same as it was before the dam, but the water level was lower. They estimated that if water levels had not dropped, the same swamp would have been inundated for 47% of the time (page 39).

The question is, if the overall amount of water is the same, why is the water level lower?

The Changing Shape of the Apalachicola River

Congress mandated that the US Army Corps of Engineers build the Woodruff Dam in the 1950s. They also mandated that the USACE maintain a 9 foot deep by 100 foot wide “navigation channel,” to facilitate barge traffic on the Apalachicola.

As Dan Tonsmeire explains, this was achieved in a couple of ways. “One is they would dredge the high spots in the river out, and they would snag the river.” Snags are the trees that have eroded or otherwise fallen off of the river bank and into the river channel. These can present an obstacle to boats, but still have an ecological significance. As Dan explains, they also took living trees and stumps off of the bank. Removing those root systems caused erosion, widening the river.

The ACE also cut off river bends, and installed dikes along the banks to straighten the river. Additionally, because sediments flowing from the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers were trapped behind the dam, river flow carried sediments from the Apalachicola river bed without replenishing them, deepening the channel for about 40 miles below the dam. (Page 6)

Because of the river’s modified, wider shape, it takes more water for it to reach its pre-dam height. “In the example in figure 13, the selected discharge of 15,000 ft3/s at the Chattahoochee gage had a pre-dam stage of 49.22 ft, and 25,700 ft3/s is the ‘equivalent-stage discharge.'” (Page 22) In other words, for it to reach the same height (49.22 ft) as it had before the dam was built, it would need 10,000 cubic feet per second more of water to flow through it.

This also means that it takes more water than it used to to reach the height needed to enter the floodplain. And so that’s a factor.

Not Just How Much Water, But When

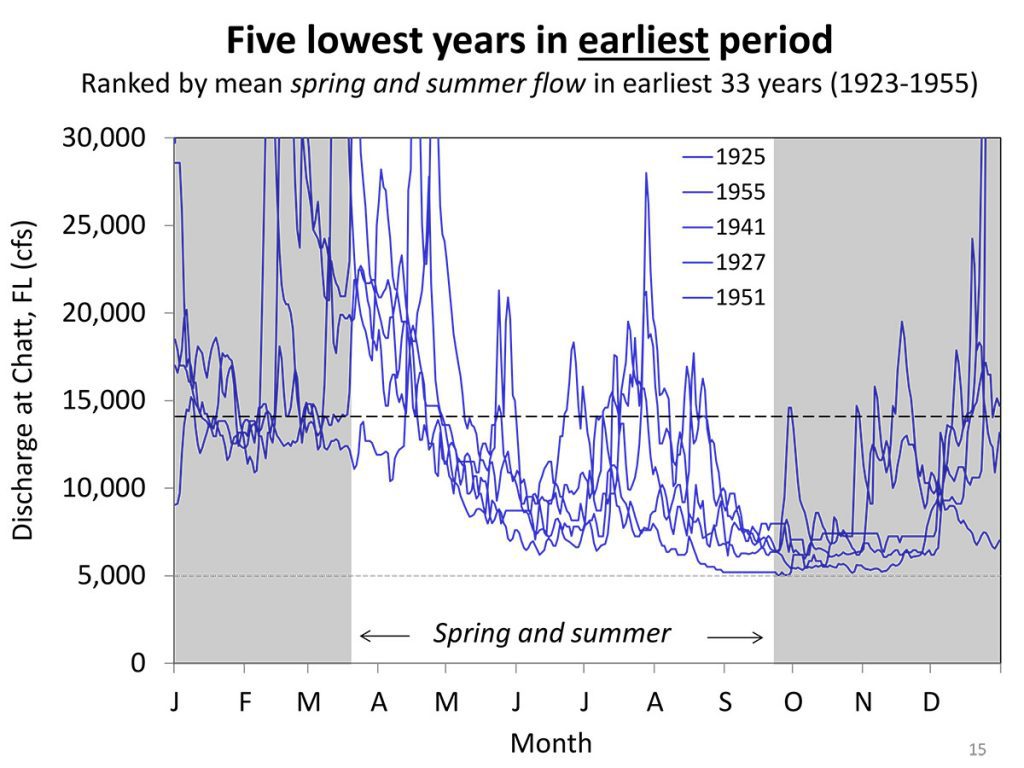

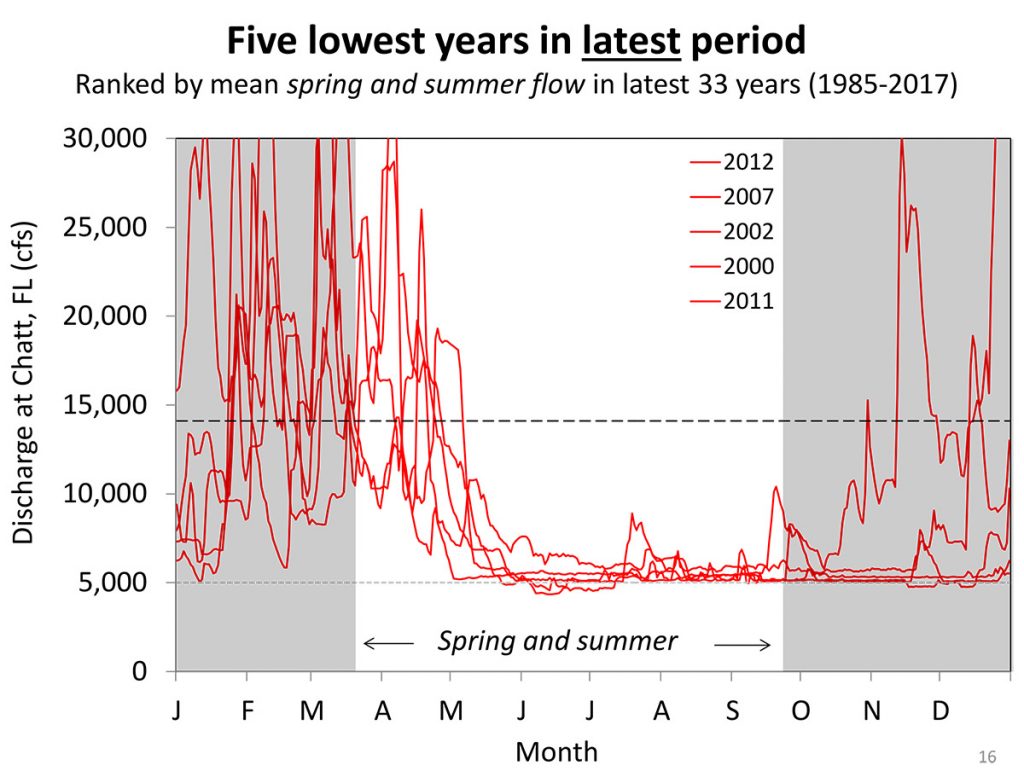

The study also notes that while the overall discharges were the same over their study period, they were lower during an important seasonal period. Talking to Helen Light, she pointed me to how much water is released from the Woodruff Dam during the spring and summer months.

This is a growing season for crops in south Georgia, and the Army Corps of Engineers reserves water behind the Woodruff Dam when there is drought during these months. But growing season for cotton is also the growing season for tupelo trees.

Older tupelo trees are more resilient, and can sustain drought, while younger trees in the subcanopy are vulnerable in dryer conditions. And it can take decades for a tupelo tree to reach maturity.

A chart showing the five lowest flow years along pre-dam Apalachicola River, by month. Courtesy Helen Light.

The chart above shows the five lowest flow months on a pre-dam Apalachicola. In other words, the driest drought years. Note that even though it got as low as 5000 cfs (the absolute minimum that is allowed to flow from the dam today), there are spikes during the summer months.

A chart showing the five lowest flow years along Apalachicola River, after the construction of the Woodruff Dam, by month. Courtesy Helen Light.

Now look at the five lowest years after the dam. This includes the record drought of 2012, when the dam released the minimum 5000 cfs for 10 months. Notice the flatness of the summer growing season.

A chart correlating the lowest and highest flow years’ spring and summer flows on the Apalachicola River, pre- and post- dam. Courtesy Helen Light.

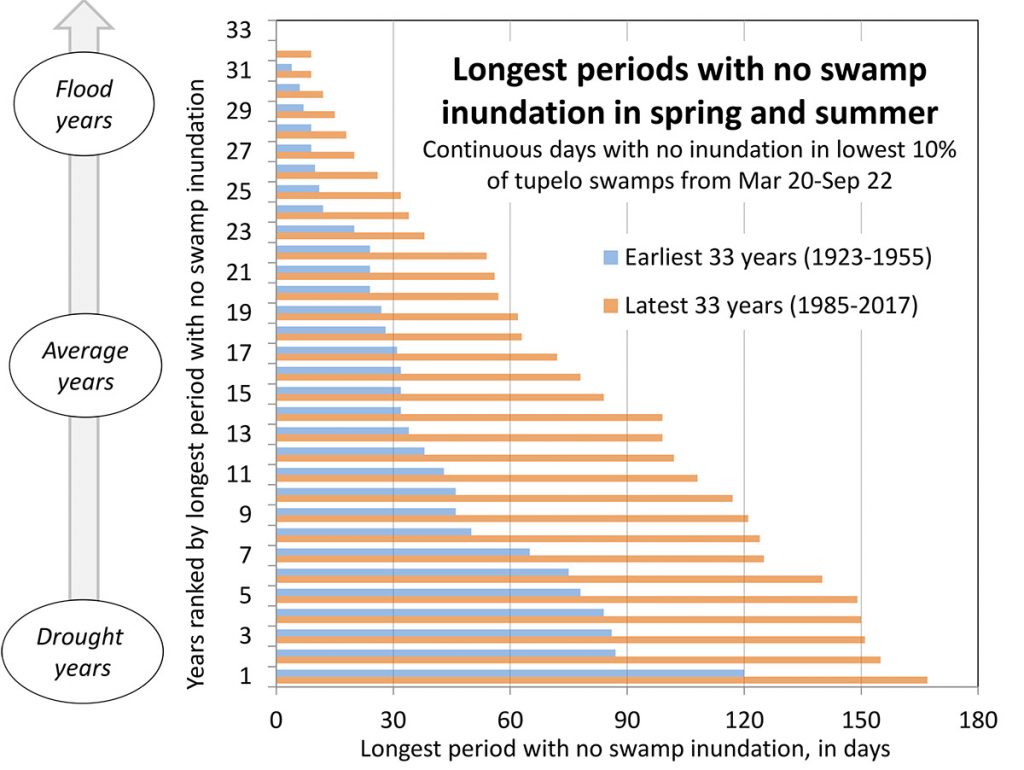

Helen wanted to make sure that these weren’t outliers. This chart matches the lowest and highest flow years of the pre- and post- dam. So the driest year before the dam was built is matched with the driest year from after, the second driest pre- and post-dam with each other, and so on. For each year, Helen has shown how long, in days, her study swamps went without inundation. You can see that swamps were dryer in every correlating year after the dam was built.

When Dan says that no new tupelo trees are replacing the older ones, this is why. Tupelo species need water more than any other tree in floodplain swamps, and they’re also the most numerous. But they’re not getting the water when they need it most. So, looking at how many of those younger trees are in the subcanopy, Helen can estimate how many will grow to become the trees that form the canopy. Here is that projection:

You can see how much was lost between 1976 and 2004 on the canopy and in the subcanopy. While there has been a loss of mature trees, there’s been an even greater loss of the younger trees that would replace them.

Saying Farewell to Riverkeeper Dan (kind of)

Dan drives us to our second location, Poloway Slough. As we slow down, I notice a few ducks ahead- a mother and two ducklings. Seeing us, they swim into a less visible location along the slough. When we hop out of the boat, we see a barred owl scanning the slough. It has likely seen the ducks as well.

As Georgia and Dan say in the video, every time you go out on the river you see something new. There’s a chase, and the mom appears to draw the owl away from her ducklings. The owl flies around out of site, and returns to its perch empty-taloned. I can just make out the mom far away down the slough, where she catches up with her young.

Dan’s knowledge of these backwater places is a big part of his deeper understanding of the Apalachicola River and Bay system. The idea behind the video is that Dan is passing knowledge on to Georgia, but she’ll earn a lot of that knowledge the same way he did- one exploration at a time.

His explorations in our area began in 1982, when he moved to Dog Island from Alaska. All of his moves seem motivated by a desire to find a perfect river and bay.

Dan Tonsmeire grew up by Mobile Bay, in Alabama. “As young kids, we were swimming and drinking out of side streams… everything was healthy and productive over there. And over the course of my twenty years of growing up, you couldn’t swim in the river because you’d get hepatitis. So I moved out west, thinking I’d find a place.”

Dan ran rivers for ten years in Alaska before he began to miss the Gulf of Mexico. That brought him to Dog Island to work for the Nature Conservancy. He really began to get to know the river as the Apalachicola coordinator for the Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program, for the Northwest Florida Water Management District. In 2004, he became the Apalachicola Riverkeeper.

I met him in 2012. I signed on to participate in RiverTrek that year, jumping at the chance to shoot video along the entirety of the river. A month before we set off, the Apalachicola oyster fishery collapsed, giving a new significance to what would become a two part piece. Dan drove the support boat for RiverTrek, and he spent every spare moment he had on my first couple of RiverTreks calling legislative aides, ACF Stakeholders, and journalists.

When I paddled in 2015, my four year old son Max needed distracting while I set up my tent on sandbar near Wewahitchka. Dan gave him blueberry muffins and read him an advocacy piece he was writing on his laptop. It seemed he was always working.

Now that he’s retired, he gets to slow down a little. But he’ll remain active with the Riverkeeper organization. I don’t think he can stay off of the river. “I know the organization is in good hands, and I want to continue to help them move that ball in positive direction.”

Dan tries to get a red dot to show up on his Google Earth App, and Georgia shoots me while WFSU videographer Christian Summersill and I shoot her back.