Dr. Walter Tschinkel has developed a novel way to explore ant nests. We travel with him to the Apalachicola National Forest for a brand of research that creates works of art, in collaboration with the ants themselves. You can see an exhibit of this art at the Tallahassee Museum through June 10, 2018.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

I think all of us at some time have stepped on a mound of dirt, uncovering scores of scurrying ants. Immediately, we brush them off our feet before they can bite us. When we see lines of ants crossing grass, we chose a different spot in the park to have our snack. And we’re definitely unhappy to see them in our house. When we see ants in our world, they’re pests.

Visiting the Apalachicola National Forest with Dr. Walter Tschinkel, we enter their world. We’re in a section of the forest just south of Tallahassee that Dr. Tschinkel calls Ant Heaven. When we look at the hundred or so species of ants here like we look at the other animals of the forest, they can surprise us.

For instance, while ants are all small to us, they have a wide range of sizes. “So you have little tiny ants,” Dr. Tschinkel tells me. “They look like walking grains of sand… and then you have ants, like carpenter and and harvester ants, that are a 1,000 to 1,500 times the weight of those small ants.”

Ants are also diverse in their habits. Some are fungus farmers, where others are predators. Florida Harvester ants have some interesting habits, seemingly without purpose, that we’ll examine in a second.

And then there are their nests. This has been the most recent focus of Dr. Tschinkel’s research. Not only have his findings rewritten our conception of how ants live underground, but they’ve produced what is essentially art, and a new way to bring people into the world of an animal we usually avoid in nature.

Ant Nest Casting: Blurring the Line Between Sciences

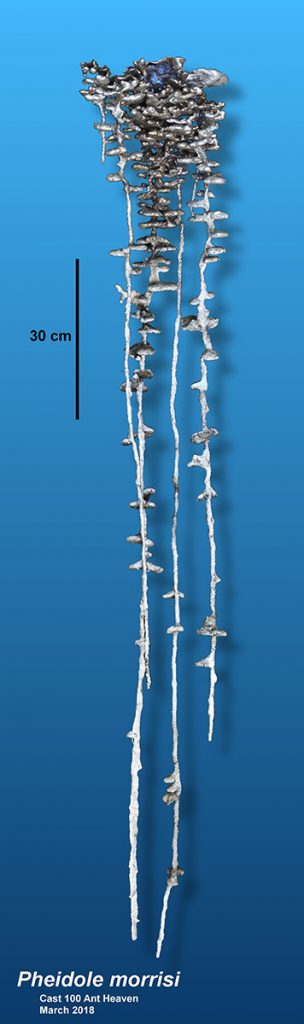

Today, Walter Tschinkel is making a casting of a Pheidole morrisi, or Morris big headed ant, nest. This is the most common ant species in the Coastal Plains forest of north Florida. He chooses a nest and sets up next to it.

In my years of working with biologists, I’m always amazed at the research tools they invent and build with materials available at your local hardware store. Pavers and ceramic tiles become oyster spat tiles, and sheets of metal create drift fences around ephemeral wetlands. Walter Tschinkel’s kiln, however, is a bit more elaborate.

Its largest component is the body- a metal trash can. The inner chamber is lined with insulation, and its lid has been fitted with a long chimney. Dr. Tschinkel needed his kiln to get hot enough to melt aluminum and zinc, an engineering feat for which he had to go back to his college chemistry and physics classes.

“Science isn’t really all that compartmentalized.” He says. “We do teach it as biology, chemistry, physics, and so on, but in fact the overlap among all those disciplines is really extreme. If you want to build a kiln, you need to know a little bit of chemistry, a little bit of physics, like gas laws, and combustion, and those kinds of things. And then, basically, it’s a question of solving problems.”

He lines the inner chamber with charcoal, and lights pine cones and needles to start it burning. He closes the chamber and we wait.

A Three Dimensional Map of an Ant Colony- in Metal

In a little while, the fire is hot enough. The aluminum will be placed in a steel crucible, and the crucible will be placed into the fire. But first he coats it with boron nitride, a heat and fire resistant chemical compound.

Dr. Tschinkel used plaster for his first castings of fire ant nests. He suspected the nest architecture would be similar to cross sections he’d dug up. However, “Instead of a chaotic swarm of chambers, they were actually quite strictly organized into vertical shafts and horizontal chambers. That was quite an epiphany.”

In fact, he found them to be quite beautiful. He wanted to display them, and thought a metal casting would be more attractive. So he designed a kiln he could lug into the forest.

He melts bits of scuba tanks that failed pressure tests, and leftover ingots from previous castings. It not only has to melt, but be hot enough to not cool and harden right away. Otherwise, the metal wouldn’t reach the bottom of the nest.

When the molten aluminum is just right, he brushes off the mound. It’s easy to think of this pile of sand as the ant’s home; as we soon see, it’s not much more than the front lawn. The molten metal makes it down several feet, filling every negative space in the nest.

He digs a hole alongside the nest to extract it. The metal didn’t reach the bottom of the nest, so he does a second pour and continues digging. The nest is deeper than he is tall, and so after a while, he’s beneath the surface level.

With a little soldering, he has a full Pheidole morrisi nest.

Ant Diversity in the Apalachicola National Forest

Pheidole morrisi is the most common species in the forest, but it’s only one of a hundred or so species found in our area. Each has its own ecological niche, and exhibits different baheaviors. Some are quirkier than others.

These are ants that like dry, well drained soils. “About a quarter mile to the west here,” Dr. Tschinkel says, “you get into the flat woods. And in the flat woods, the water table is about an average of a meter below the surface.” He points in the other direction, to the Fisher Creek wetland area. “The water table from the flat woods drops 30-40 feet to go down the wetlands.”

Right where we are, ants aren’t likely to dig deep enough to reach water. This is why there is a dense and diverse concentration of ants here.

Dr. Tschinkel and I spend a minute looking at Forelius pruinosus, a species with no common name that I could find. As he tells me, they always march in a line. They tended to blend into the background when I took still shots of them, so here’s a short video of them marching.

We also look at Trachymyrmex septentrionalis, a fungus gardener. As Dr. Tschinkel shows us in the photo below, it mounds dirt on the sides of its nest entrance (where he’s pointing).

At the beginning of the video, we see the Florida carpenter ant, Camponotus floridanus, which makes small, scattered nests. That video was taken at his exhibit at the Tallahassee Museum. It’s one of the two largest species of ant in the forest.

The other is the species that most drew him to Ant Heaven: Pogonomymex badius– the Florida harvester.

A Florida harvester ant nest in the Apalachicola National Forest. Note the charcoal around the edges of its mound.

The Distinctively Decorated Nest of a Florida Harvester

The Florida harvester makes unique use of its habitat within a fire climax ecosystem, though not for any reason scientists have yet to understand.

This is a sandhills environment, which, like the upland flatwoods, is a habitat dominated by fire dependent longleaf pine (many of our modern forests were once pine plantations, and have a mix of longleaf, slash, and loblolly pine). The trees themselves provide fuel for fires that would have, on average, spread through the forest every two to three years. They do this by dropping dry pine needles.

These needles then burn, creating bits of charcoal. When you walk in the forest, you may see ant mounds with this charcoal arranged along their sides. This is the home of the Florida harvester.

Not only do they decorate their nests, but they are always rearranging the charcoal. As far as researchers can tell, there is no practical purpose for this nest adornment. As Dr. Tschinkel explains, “We’ve tested eight different hypotheses at this point, and none of them were supported.”

They also move their nests about once a year for reasons that are not readily apparent. Dr. Tschinkel has tagged each active nest, and visits then 7-8 times a year to see if they moved. When they do, he moves the tag, and keeps track of their moves over time. As you see in the video, they seem to move around a central spot. Again, no one really knows why.

This is a tag Dr. Tschinkel uses to mark he current location of harvester nest 98. Since he now has over 600 numbered nests, he can tell this is one of his earlier nests, having first been marked about eight years ago.

The Florida Harvester- Underground

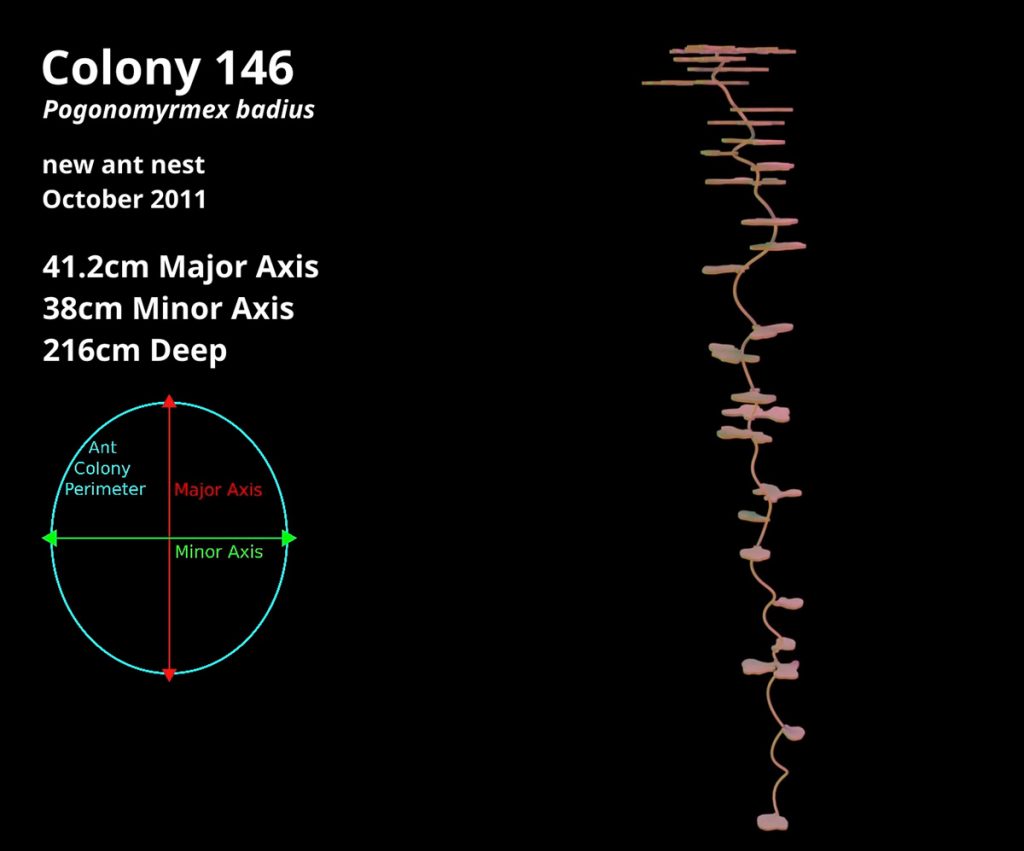

When we look at the architecture of a harvester ant nest, we can see that it’s probably a bit of work to make. So they’re creating a lot of work for themselves by moving so often.

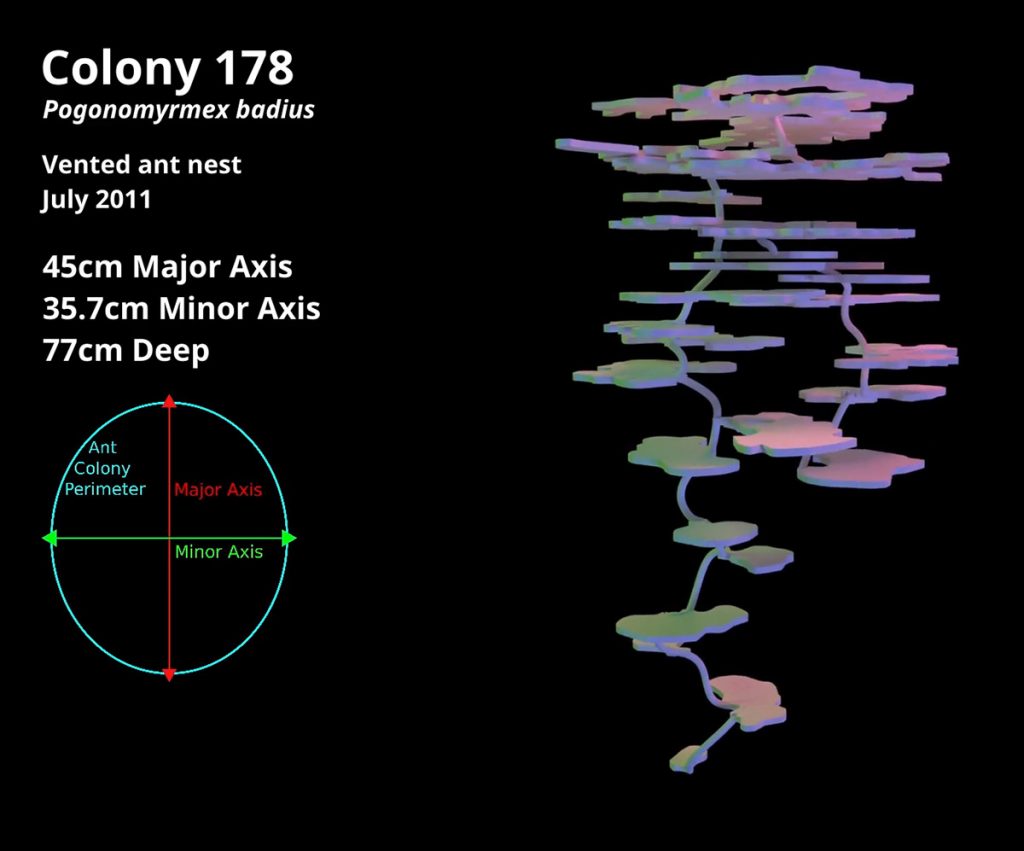

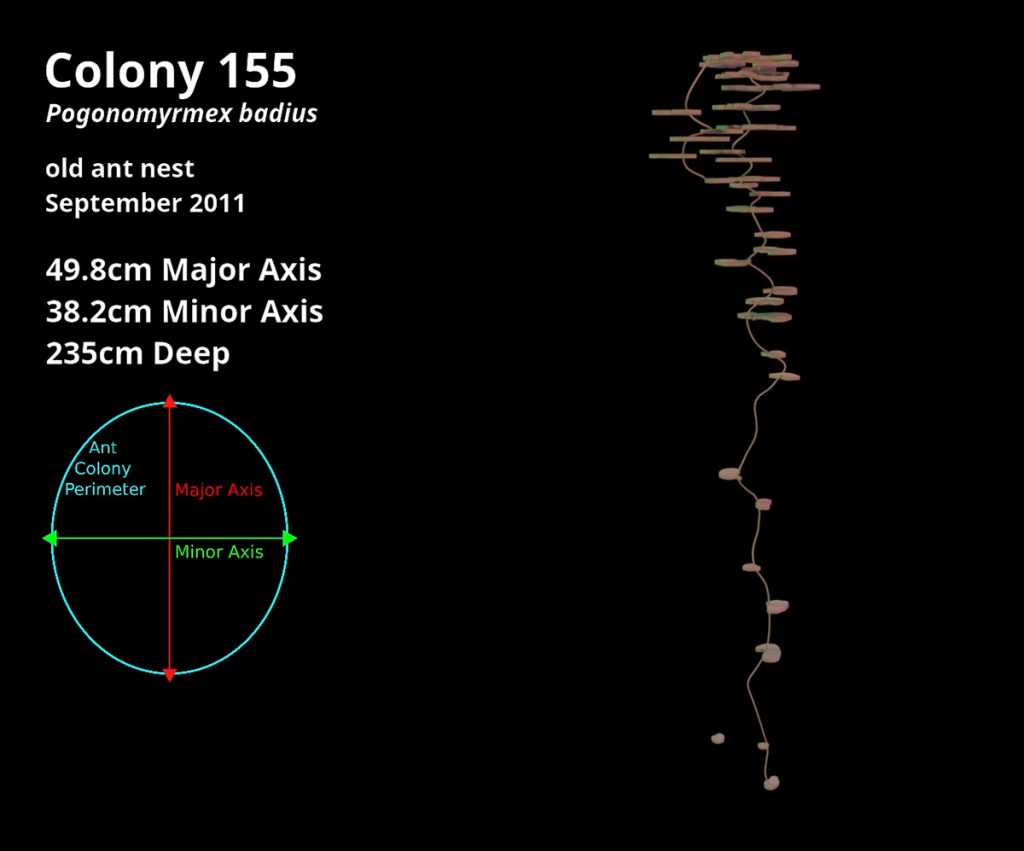

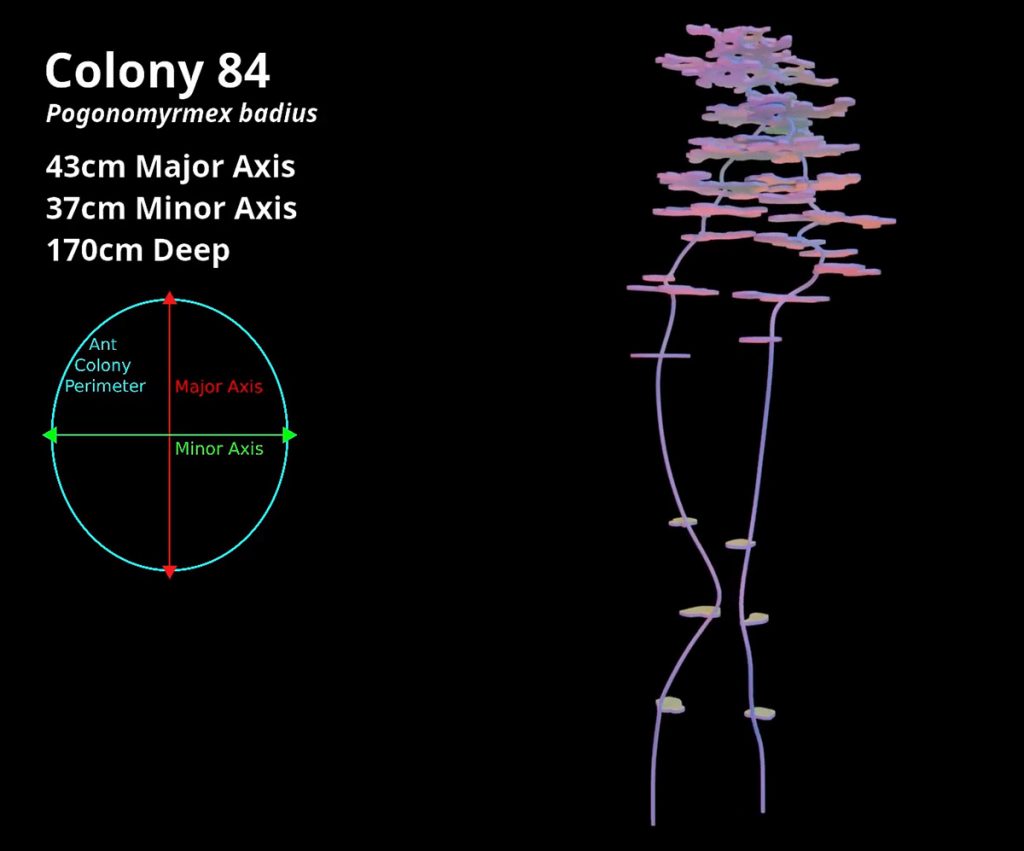

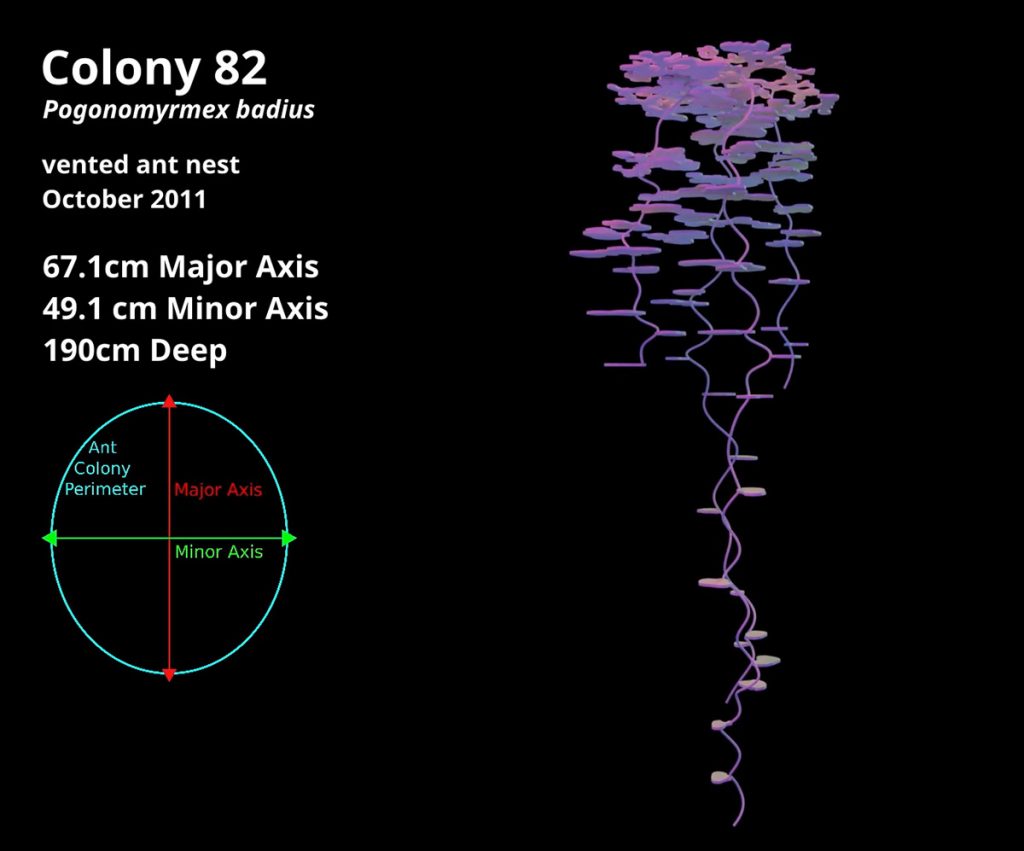

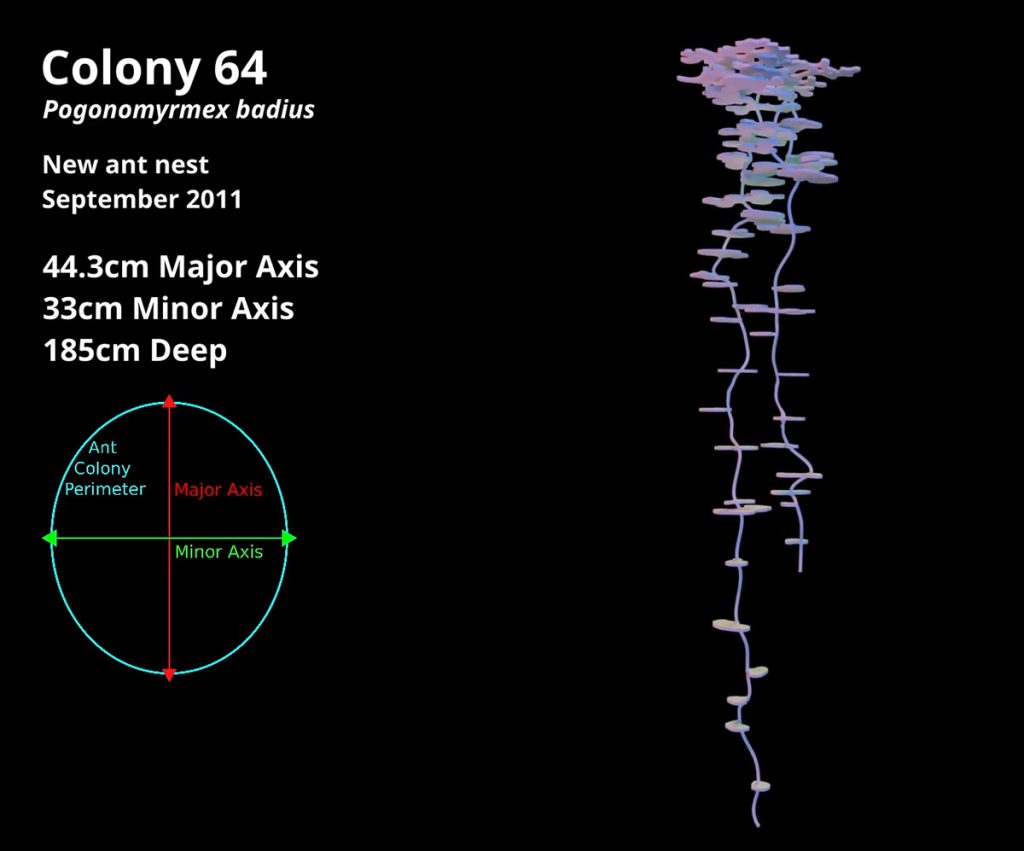

The following are frame grabs from animations created by Daniel Julio Dominguez, Dr. Tschinkel’s field assistant. These are digital renderings of their physical counterparts, castings of Florida harvester colonies. As you can see, they are quite complex, and large (for the metric system challenged, 235 centimeters is over seven feet deep).

In Defense of Fire Ants

The ants we’ve been discussing are our local ants. But if you live in an urban/ suburban setting, you’re not likely to see them by your home.

“The most common ants in yards, and roadsides, and parks, and all kinds of those kinds of habitats, are fire ants.” Says Walter Tschinkel. However, “the fire ant is an exotic from Argentina.”

Fire ants were the first ants he studied, starting in the 1970s. He chose it because even though it was introduced, accidentally, in the 1930s, it’s the most abundant ant in North America. That’s because it is incredibly efficient at colonizing disturbed areas, places where we’ve torn up the ground and built.

Most of us who consider ourselves nature lovers have a disdain of exotic invasive species. Having studied fire ants, though, Dr. Tschinkel can appreciate their ruthless effectiveness.

“If we can get past that emotional response that people have for fire ants, it’s really a fabulous, interesting animal. And it is very good at what it does…. There’s another opportunity for us, intellectually, to learn about what fire ants are, what they do, and how they make a living in the habitat we made for them.”

In 2013, Walter Tschinkel published a book on his 30 years of fire ant research, called The Fire Ants.