Earlier this month, we delved into archeological mysteries on the Saint Marks National Wildlife Refuge. Today, we return to the Spring Creek section of the Refuge with the same archeologists as they predict the location of a village over a thousand years gone.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

There are no ancient stone temples in the St. Marks Refuge. It would be easier for archeologists if there were. But the people who lived here for thousands of years lived in wooden homes that long ago turned to dirt.

What they did leave behind were mounds. People living in the Woodland era (0 – 1,000 AD) buried their dead in what Dr. Michael Russo says were “smooth, cone shaped, beautifully symmetrical mounds.” Dr. Russo is an archeologist with the National Park Service and, again, his work would be easier if these large landmarks remained intact. But they haven’t, thanks to extensive looting over the last century.

We’re in an off limits part of the Refuge near Spring Creek. The NPS’s Southeast Archeological Center is in the early stages of excavating a site here. This is a tangly hardwood forest not far from the coast, and we have to fight our way through vines and branches as we move between shovel test sites. At one point I put my elbows on the ground for a shot, and immediately see ticks crawling up my arms.

How did we come to be here? In a landscape devoid of pyramids and large statues, archeologists have to know what to look for. And Russo, Jeffrey Shanks, and their colleagues at SEAC have been looking for decades.

Andrew McFeaters performs a shovel test near Spring Creek in the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge.

Where There’s a Mound…

Three weeks ago, we first met Jeffrey Shanks and Michael Russo, and got to know the work they do. I recommend that anyone read that post first, and then circle back to this one (I’ll still be here when you get back). Some of you didn’t click, so here’s the fast version.

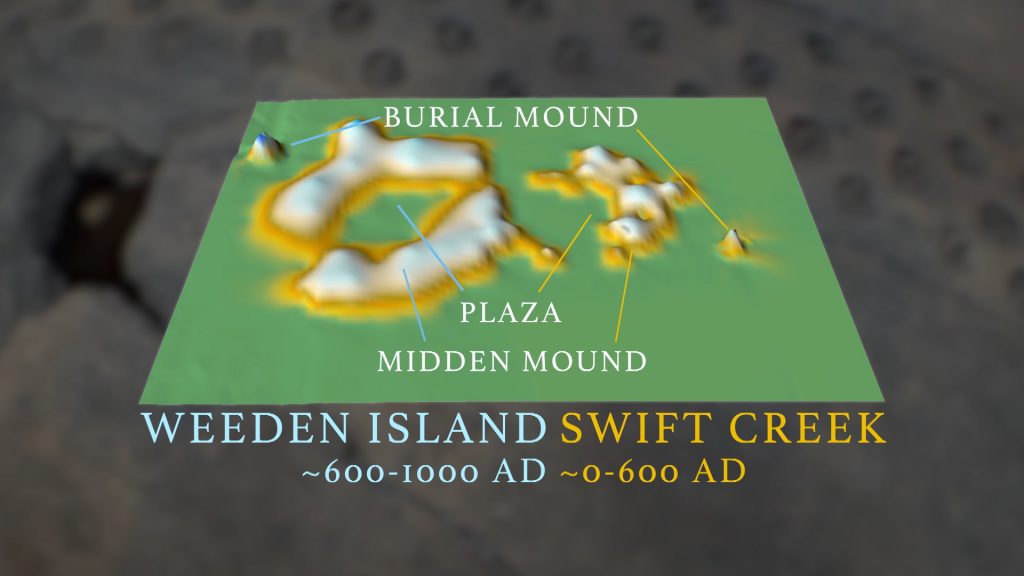

Shanks and Russo have been studying cultures from the Woodland era: Swift Creek (~0-600 AD) and Weeden Island (~600-1,000 AD). They’re the same people, but their pottery changed and they moved their villages (slightly) in the seventh century AD. So Swift Creek became Weeden Island.

The most important things we learned three weeks ago (pertinent to this story) were:

- The layout of their villages.

- The archeological techniques archeologists used to learn about a people who wrote no text, and whose houses, as I said before, are now dirt.

Basically, SEAC archeologists learned about villages they couldn’t see from what was left behind- their trash. Specifically, circular mounds of food waste that encircled what was likely a living space.

Additionally, the newer Weeden Island burial mounds and funerary pots hint at a religious change. But that’s not as important for today’s story. What’s important is that, in sites across northwest Florida, every village had a burial mound nearby.

Knowing this, our archeologists turned their attention to Spring Creek. Here was a known burial mound, but with no known village. How do they begin to look?

A topographic map of the Byrd Hammock archeological site, provided by the National Park Service. I shared this three weeks ago, but it’s helpful to see the shape of a Woodland period village and in relation to the burial mound.

…There Should be a Village Nearby

I described the site earlier. It’s hard to see too far in any direction. This is the area adjacent to the Spring Creek mound, which, based on pottery taken from the mound*, is known as a Swift Creek era site. Walking around it, there’s not much to see. At least, not until we get to a dry creek bed.

Here, we see oyster, conch, and lightning whelk shells. And as Shanks tells us, any time you see shells in the woods, you likely have an archeological site.

Over time, this creek bed has likely moved as waterways do, and cut into a midden- or trash- mound.

So we have a burial mound, and evidence of a nearby village. But how do we start to imagine what this village looked like? We know that Swift Creek and Weeden Island villages were surrounded by ring or c-shaped midden mounds. But that shape isn’t obvious in this forest, and the mounds may have worn down with time.

So researchers have to take a systematic approach, and methodically uncover the shape of this Swift Creek village.

The Spring Creek Village Takes Shape

When Michael Russo started in archeology, people referred to these midden mounds as villages. That’s because archeologists couldn’t find any trace of an actual village, so the village’s garbage became its identity.

But Russo became curious about the empty space next to the midden, where people likely lived. He wanted to give that space a shape.

“So I just started inventing a methodology where every few feet, systematically, I would go across an area near a midden to see what the shape of the midden actually was, and to see where the empty spaces were.” He says.

Here’s what that process looked like at Spring Creek:

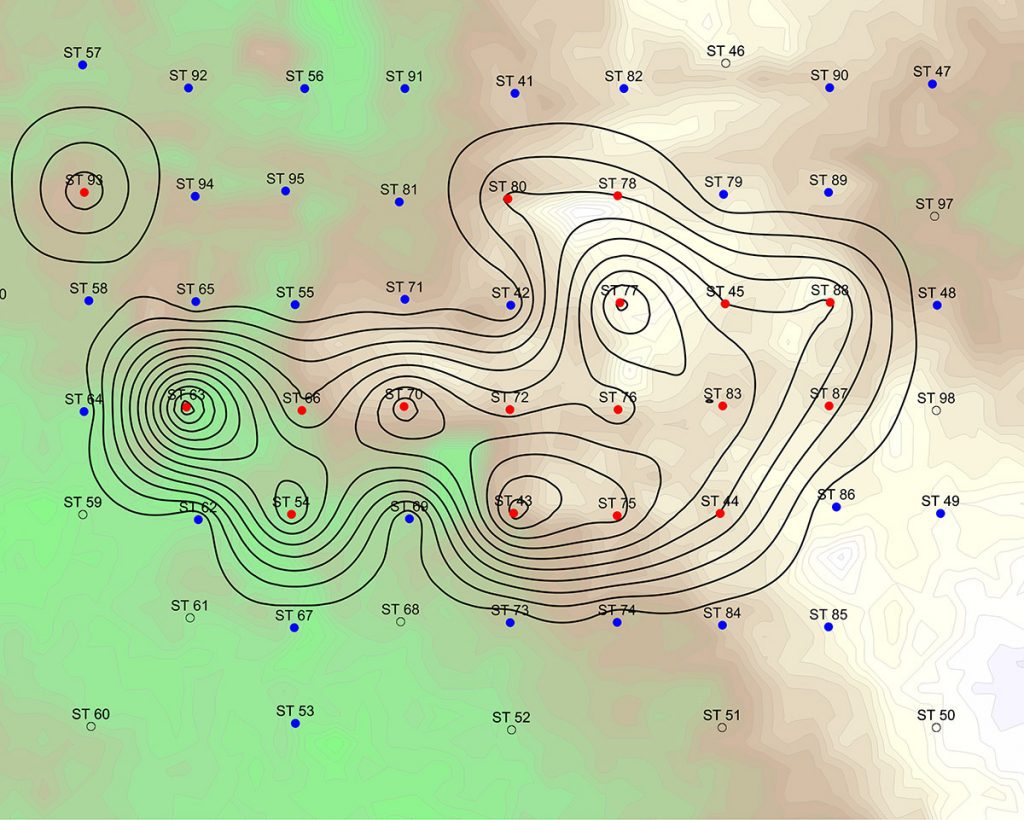

The dots on this map represent shovel tests, dug 40 meters apart. The red dots are where they found midden. This means shell, mostly, but also deer bones, pottery fragments, and even the rare arrow tip (you see a freshly discovered arrowhead at 4:14 in the video).

Emily McGann, an intern, discovered this Swift Creek arrowhead during a shovel test at Spring Creek. An FSU student, we last saw her in the water at the Ryan-Harley site during our most recent segment on Wacissa River archeology.

Aside from rock and bone, they find important archeological artifacts called coprolites. This is poop. While most of their food waste has decomposed, the coprolites they find aren’t entirely fossilized, and can still be analyzed for information on what people ate here.

And even beyond all of the solid objects in the ground, the soil itself is a midden indicator. As I covered in last week’s post, all of that decomposed food waste created a darker soil than the sand that covers the ground here. And since this mound is mostly buried now, measuring the height of this darker soil can give archeologists a better three dimensional image of what it had looked like.

SEAC archeologist Andrew McFeaters scraped midden soil (top) and non midden soil (bottom) to illustrate the difference in darkness.

Sharpening the Image

Their initial shovel testing is somewhat like a game of Battleship. When you get hits, you concentrate on the areas around them. Below, you can see the second round of shovel tests, now at a tighter 20 meter increment, clustered a little bit more around their initial hits:

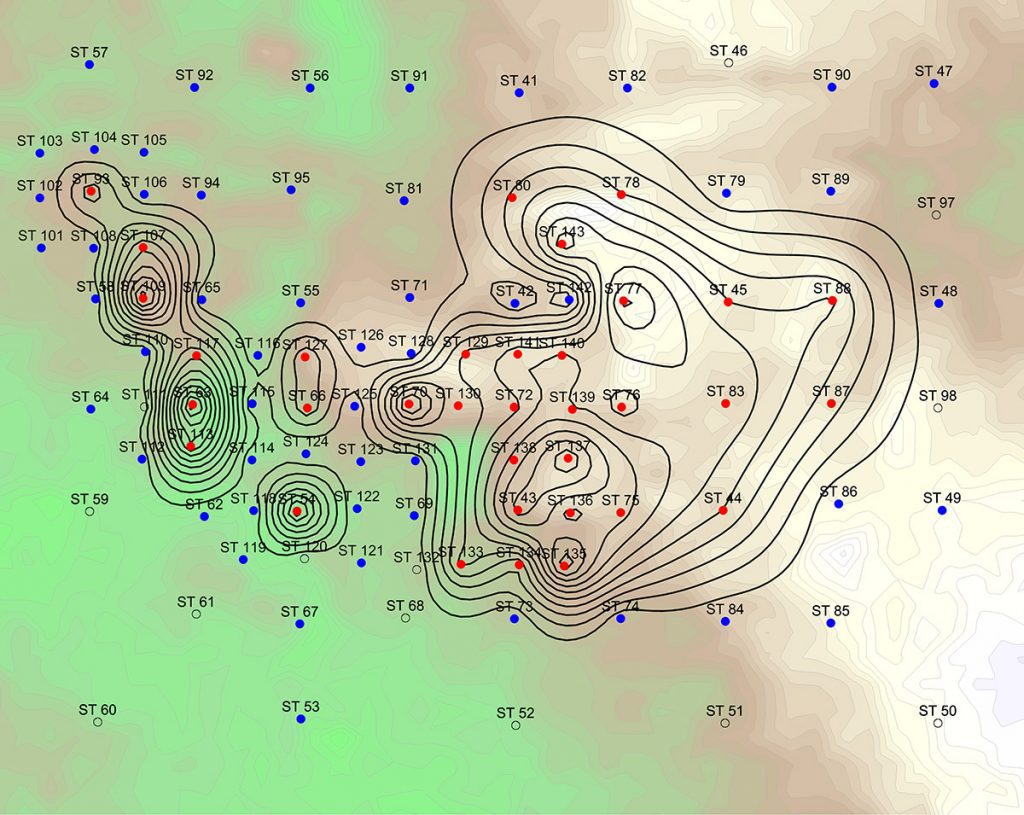

And finally, they tightened their search further, digging at 10 meter increments:

Here, the midden started to take shape, something like a “c”. And so now they have an empty space as well, the place where villagers lived, cooked, danced, and performed ceremonies.

Context and Looting

A couple of times in the segment, you can see some of the charts and notes the SEAC archeologists have made regarding their excavations. They dig in 10 centimeter increments, and they chart every find’s coordinates within the sediment layers. They find some artifacts a layperson would immediately recognize as important- arrowheads and pots shards- and others we might not- shells, poop, and dirt. The information of how they’re found together in the ground, in relation to each other, tells the story of the people who lived here. As does the shape of the midden mound.

The story, Jeffrey Shanks says, is what matters. Everything else is an object. Unfortunately for archeologists, those objects have a dollar value to collectors. And so sites are torn up, illegally, and context destroyed.

The Spring Creek mound was discovered by Clarence Bloomfield Moore. If you Google him, you can see him identified as an archeologist, amateur archeologist, or artifact collector. He traveled the southeast, excavating burial mounds (*something contemporary archeologists don’t do, out of respect for those buried within them).

He took good notes for the time, which has been a help and a hindrance to archeologists. On the one hand, Moore identified sites and found much of the pottery that defined the Swift Creek and Weeden Island eras. On the other, his detailed notes guided generations of looters to these sites.

Burial mounds have been especially hit hard. “There’s not a single burial mound in north Florida that hasn’t been looted.” Says Michael Russo. This makes sense. Middens are trash heaps, and the villages themselves are mostly devoid of artifacts. Burial mounds, however, were filled with ceramics.

The truth is that, by now, these sites have all been picked through pretty thoroughly. The good artifacts, the ones that someone might be hoping will fetch a tidy sum on the black market, are all but gone.

But the story remains. Archeologists are, using the best scientific methods available, slowly bringing the story into focus. The more intact their sites, the easier this is. With that in mind, Russo says they’re applying for National Landmark status for their sites.