A family of three is on a mission to see how far away they can get from people. They are Remote Footprints. Today, the Means family leads us into the Bradwell Bay Wilderness, our remotest local area.

Music in the video was composed by Hot Tamale, who just happen to be this weeks musical guest on Local Routes.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Media

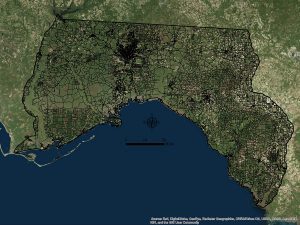

The most surprising moment of our remote adventure didn’t happen in the swamp, or in the forest, but in front of a computer. Rebecca Means clicked a check box, and all of our area roads loaded onto her map. Our rural, forested Big Bend of Florida wasn’t as open as I had thought.

A map showing roads between between the Suwannee and Apalachicola Rivers. Image created in ArcGIS by Rebecca Means.

Ryan and Rebecca Means started Remote Footprints to answer what seems like a simple question. How far away can you get from people in each of the 50 states?

It wasn’t enough to feel far away (qualitatively remote); there are places in city parks where I can surround myself with trees and not see people. Ryan and Rebecca are scientists, and they needed something numeric, so they could say that spot A is more or less remote than spot B (quantitatively remote). The number they chose to define remoteness: the furthest distance from roads.

Remote Footprints | Family Vacation Turned Multi-year Project

Ryan and Rebecca Means are biologists with the Coastal Plains Institute. Most of their work takes place in the Apalachicola National Forest, where we’ve covered their striped newt repatriation project. It’s a job that sees them outdoors a great deal, often with their daughter Skyla in tow.

Technically, Remote Footprints is operated as a part of CPI. It’s a scientific endeavor. It takes a lot of planning and data processing. Sometimes, they require permits to approach a remote spot.

They put a lot of work into something that started as family vacation idea.

Looking at the photos they gave us to use in the video, these are amazing adventures. It’s work, but it must be exhilarating to execute each adventure, to scratch one more state off of the list. When they’re done, they can say they went to the remotest spot in all 50 states. And so will Skyla.

After all, Remote Footprints isn’t just the passion project of two biologists. It’s part of a parenting philosophy.

“We wanted her to be imprinted on something like this instead of imprinted on a TV show, or on a computer.” Rebecca said. “And so this is her norm. We wanted this to be her norm versus sitting on a couch.”

The project started when Skyla was ten months old, and for years she spent long hours on Rebecca’s back. There were multi-day trips that involved canoeing, boating, camping, and/ or hiking steep terrain. You can get a sample of the varied landscapes they’ve encountered in the photos at the end of the video.

Ryan and Rebecca wrote Expedition Journals for each of the 33 state remote spots they have visited. In them, you can see the planning that went into each trip, and the various obstacles they overcame.

What is the Big Bend Remote Spot?

Now, we don’t have a huge travel budget, and our focus is local ecology. For our purposes, Rebecca calculated the remotest spot between the Suwannee and Apalachicola Rivers. This is the Bradwell Bay Wilderness area in the Apalachicola National Forest (ANF).

Wilderness Areas are some of the most protected wild spaces in our country. You can read more about Wilderness Areas and the Wilderness Act of 1964 in a blog post from a 2014 adventure. Where the massive ANF is crisscrossed by a network of dirt roads, none of those run through Bradwell Bay.

Orange blazes mark the way on the Florida Trail. Here in the Monkey Creek Swamp, blazes are painted high on trees so that they’re visible when the swamp floods.

Most people travel across this Wilderness on the Florida National Scenic Trail. This stretch is known as one of the most difficult trails in Florida. It runs through the heart of the Monkey Creek swamp. As Ryan says in the video, the swamp is “one of the only places in our local region, the Big Bend of north Florida, where you can go see a virgin stand of timber.” After walking among huge, old growth slash pine and cypress trees, we would go off trail. Then, the real adventure would begin.

Crossing as it does through the heart of a swamp, hiking the Florida Trail in Bradwell Bay often means wading in waist high water. When the water is this high, there is no obvious path. People get lost. Did we mention that Bradwell Bay is kind of remote?

It’s a trail you approach with caution, and planning.

Lucky for us, we made our hike in December, before heavy rains filled our rivers and swamps. We walked on dry ground, and enjoyed the tall, thick wetland trees towering above us.

Hiking Bradwell Bay | Longleaf Pine Uplands

Before entering the swamp, the Florida Trail leads you through pine uplands. Though this is a dry, fire dependent ecosystem, the area around the swamp had a lot of “wetter area indicating” plants mixed in with longleaf and slash pine, and palmettos.

One of the dominant plants in Bradwell Bay is a wet loving plant known as swamp titi. It grew among the longleaf and slash pine, and when we finally went off trail, in the swamp, this is what we hacked through. In December, when we went, the swamp titi had lost its flowers and gone to seed.

This is a pitcher plant (Sarracenia species) in its dormant state; it won’t flower until the spring. This is a carnivorous plant found where wet habitats meet the dry uplands. You hear Ryan describe such inter-habitat areas as ecotones in the video. You can see sphagnum moss on the ground around the pitcher plant.

This isn’t sphagnum, but another kind of moss (if you know what kind, please please please leave a comment below!). Multiple species of moss covered a lot of the ground, as well as stumps and hummocks.

Hiking Bradwell Bay | Monkey Creek Swamp

Standing at the edge of the swamp, we saw the remains of a fire. The longleaf pine ecosystem thrives on fire, and requires more frequent burning than any other habitat on our continent. This fire keeps swamp plants from branching too far out wetter areas where fire won’t burn as often. It also, as Ryan says in the video, creates space between dry and wet terrain, ecotones where some interesting species mixing occurs.

One of my favorite features of the swamp were hummocks, these little islands around many of the trees. As Ryan explained to us, the swamp goes through cycles of wet and dry, and fires occasionally penetrate into it. Through all of this action, soil gathers around the base of trees, and hollow areas form between them.

Here, Skyla and Rebecca hug an old growth slash pine. Because slash grows faster than longleaf pine, they’re more often cultivated for timber. Planted slash often replaced what had been longleaf forest, and much of our state and national forest land still contains planted slash pine. In Monkey Creek Swamp, we see slash pine in a place where it grows naturally. This large specimen is decades, or perhaps hundreds of years, older than most of the pine we see in our forests.

Hiking Bradwell Bay | Going Remote!

We hiked along the Florida Trail until Ryan’s GPS showed that we were directly south of the remote spot. From there, we entered into a titi thicket with very little open ground. A thick species of thorny smilax vine provided an additional obstacle. Most of the 2.1 miles from the trail to the remote spot would have had us pushing our way through this tangle. We did as much as we could in a day, and when the sun started getting low, we decided to turn back.

At the point where we stopped, we were 1.3 miles from the nearest road- in this case the dirt forest road surrounding the Bradwell Bay Wilderness. This spot is more remote than the Ohio remote spot. The Bradwell Bay remote spot itself is 2.6 miles from a road- more remote than Illinois (1.4 miles), Iowa (1.5)and Rhode Island (1.8). The Florida state remote spot, located in the Everglades, is 17 miles from a road.

Calculating Remoteness

So, how do they arrive at these numbers?

It’s an endeavor made easier by modern technology. It starts with a program named ArcGIS. Geographical Information Systems (GIS) combine maps with geographical data. In this case, it’s Department of Transportation road data, which appears as an overlay on a satellite map.

Having seen how many roads crowd our landscape, it’s no surprise to learn that DOT’s data set has some holes in it. Some of these are roads on privately owned property, like timber land. Also, new roads are always being built, which makes an area’s remoteness something of a moving target.

Rebecca cross references the GIS results with Google Earth satellite images. She carefully examines everything that looks like it could be a road. She edits her GIS road data, and then has ArcGIS find the furthest spot from roads in a given area.

The next step is figuring out how to get to a spot. These are often on public land, but there isn’t always a trail. In some states, it can take days to reach a spot. They may have to carry supplies in backpacks, or in a canoe. And, now that Skyla is hiking alongside them, they need to account for the limitations of reaching a remote spot with a young child.

It’ll be quite the undertaking to complete each of the 50 states. The Alaska trip alone seemed to come up often as we talked on our hike. It will be a long and expensive adventure. When they’re done, however, they’ll have done something that no one else has. And Skyla could do it before turning 18.

“We think it’s fabulous that Skyla’s going to grow up having visited the remotest location of every state in the country.” Rebecca said. “I mean, that is something that no one can say, and here she grew up doing that.”

Further Adventures in the Apalachicola National Forest

No matter how many times we go into the Apalachicola National Forest for an adventure, it feels like we’ve barely scratched the surface of what there is to see. At 571,088 acres, it’s Florida’s largest national forest, ranging from Tallahassee to the Apalachicola River. It contains a wealth of habitat types and recreational opportunities, many of which we have explored on our EcoAdventure series:

Ephemeral Wetlands of the Munson Sandhills

Rebecca Means, of the Coastal Plains Institute, prepares to hand out striped newts to a group of young volunteers.

We’ve spent a little bit of time with Ryan and Rebecca in the ANF this last year, covering conservation work they’re doing in another part of the forest.

The Munson Sandhills are located just south of Tallahassee’s Capital Circle, containing some popular dirt bike trails connected to the St. Marks Trail.

While we explored the pine uplands of the Munson Sandhills, our focus was on the Coastal Plains Institute’s work in ephemeral wetlands. Last January, my wife and kids joined some other families to release striped newts. These little salamanders had disappeared from the area, and CPI has been working for seven years to reintroduce them.

Ephemeral wetlands empty and fill based on the water level of the aquifer below it. Striped newts breed when the ponds are full, so they were adversely affected by droughts in the 1990s and 2000s. After some success in the repatriation project last year, we attended last week’s newt release for an update on their efforts.

The Ochlockonee Bio-Blitz

On a fall day in 2015, we spent the morning on an Ochlockonee River sand bar with several families. Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy was hosting a Bio-Blitz. The mission: to observe or trap (and release) as many species of animal as possible in two hours. We saw giant swallowtail butterflies, Florida soft shell turtles, frogs, fish, and more. This aired as part of our Roaming the Red Hills series, which was funded by Tall Timbers.

Carnivorous Plants in Liberty County

The Apalachicola National Forest is home to a diverse number of carnivorous plant species. Their greatest concentration is in Liberty County. There, we visited a bog deep in the forest, an ecotone between pine uplands and and headwaters of the New River (a tributary of the Carrabelle River).

The shoulder of State Road 65, which cuts through the forest, also offers many opportunities to view pitcher plants and sundews, among other carnivorous species. The county promotes the road, which leads to Apalachicola Bay, as a wildflower viewing trail.

Owl Creek and the Apalachicola River

We’ve had many adventures on Owl Creek, a tributary of the Apalachicola. It’s a place I became familiar with in 2012, when I kayaked the Apalachicola on RiverTrek. On the final night of the annual paddle trip, ‘Trekkers kayak a mile and a half up Owl Creek to camp at Hickory Landing in the ANF.

After 2012, Owl Creek became a special place for my son Max and I. In 2014, we camped with the RiverTrek crew there, accompanying them to the main river channel before turning back to explore the tupelo swamp on our own. In 2015, Max and I concluded our 40 mile RiverTrek adventure at Owl Creek, capping our greatest bonding experience to date.

The Florida Trail Along the Sopchoppy River

On one of our first EcoAdventures, we hiked along a gorgeous stretch of the Sopchoppy River. It was my first introduction to the Florida National Scenic Trail. The river was low; this was during the dry years of 2011 / 2012. We enjoyed some great fall foliage, and met some dedicated volunteers who work to keep the trail accessible to the rest of us.