A few weeks ago, we explored the Apalachicola oyster’s connection with the Apalachicola River Delta, and the mysterious Tate’s Hell swamp. Today, we take a closer look at the oyster itself, and its embattled bay. We return to the bay next week for an adventure on Saint Vincent Island with author Susan Cerulean and FSU Oceanographer Jeff Chanton.

As in the Tate’s Hell video, music was composed for the piece by Chris Matechik. Chris plays in the acoustic duo, the Flatheads, and is a marine technician at the FSU Coastal & Marine Laboratory.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

An oyster is tonged from Apalachicola Bay. It is shucked, handed to me, and eaten just minutes after it left the water. Almost immediately, a wave of energy washes over me. This must be what Popeye feels when he eats spinach, or Mario when he eats the mushroom and becomes Super Mario.

It is, as Shannon Hartsfield says in the video, a perfect half shell oyster.

From left to right- WFSU-FM reporter Jim Ash, Shannon Hartsfield, and WFSU-TV producer Rob Diaz de Villegas. Apalachicola Riverkeeper Dan Tonsmeire looks on (bottom left).

And yet, I know I’m eating what has become a rare delicacy.

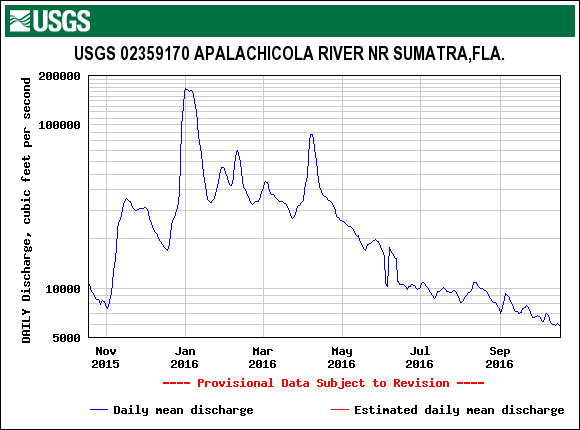

I’m here to get a sense of the bay’s recovery. Much of the news I’m hearing isn’t hopeful, and things might be getting worse. In the five months since our bay trip, freshwater flows from the Apalachicola River have plummeted. We may be entering another dry cycle.

This concerns Hartsfield, president of the Franklin County Seafood Workers Association. “If we go through another low-flow drought year, and [with] what the Corps is presenting us- we’re over with,” he says. “We’re not recovering from that.”

Drought and dams have kept fresh water from the Apalachicola oyster. Florida is taking Georgia to court to send more the oysters way. It’s not a situation that will resolve itself any time soon.

The Apalachicola Oyster Crisis: the Briefest Recap

It has been a hard four years for the Apalachicola oyster.

In September of 2012, the winter oyster bars opened. To give oysters a chance to grow and mature, oystermen harvest the bay in zones. In the summer months, they work near the mouth of the river; in the fall and winter, they’re further out in the bay. After a productive summer, the winter bars were surprisingly barren. The summer bars weren’t doing so well, either. Florida governor Rick Scott petitioned the U.S. Department of Commerce to declare a fishery disaster.

This came during a period of historic low flows on the Apalachicola River. As a result, water in the bay became saltier. Oyster predators such as crown conchs and southern oyster drills multiplied. River flows increased in 2013, but the damage had been done. The bay was in need of intensive restoration.

What will it take to save the Apalachicola oyster?

You can see it in a video we produced in January of 2013: there wasn’t much in the way of hard surface on the floor of Apalachicola Bay. So, not only was there a lack of oysters, but there weren’t many landing places for oyster larvae. Those larvae usually settle on oyster shells, a process which creates oyster reefs. But that next generation of oysters had nowhere to go.

A group of researchers laid out a recovery plan. The Oyster Recovery Task Force, made up of UF biologists and oceanographers (and our collaborator Dr. David Kimbro), recommended shelling the bay and reducing oyster harvests.

Oystermen would deposit oyster shell on spots where oysters had been known to grow. Additionally, oystermen were given lower bag limits on their catch. While they were being paid to deposit oyster shell, they didn’t harvest oysters, which also reduced stress on the reefs.

The Oyster Task Force presented three scenarios for recovery. The best case scenario required 200 acres of oyster shell added every year for five years. Their computer modeling predicted that, had this been done, the bay would have recovered by 2015. Unfortunately, there wasn’t funding for that amount of shelling.

It’s kind of a race. How much shell can be laid, and new oyster growth achieved, while river flows are good? Can Apalachicola oyster reefs become established enough to survive the next dry spell?

We might soon find out.

These readings were taken from a US Geological Survey gauge near Sumatra, FL. During September, the flow of the river plummeted towards 5,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), the minimum the Army Corps of Engineers can discharge from the Jim Woodruff Dam.

Dams and Drought in the ACF Basin

It’s day one of RiverTrek 2016, and I’m standing on the Alum Bluff sand bar. I camped here on the 2012 RiverTrek, across from one of Florida’s great geological outcroppings. From 2013-2015, the Apalachicola River was too high for the sand bar to accommodate 15-20 paddlers, so they camped upstream.

Today on the Alum Bluff sand bar, Trekkers are pitching tents.

I’ve spent the day riding in a boat with Apalachicola Riverkeeper Dan Tonsmeire, and he’s not happy about recent low flows. As he points out, Florida is not in a drought. Nonetheless, flows on the Apalachicola River have been dropping towards 5,000 cubic feet per second (cfs). That’s because the Apalachicola is a small part of a larger system- the Apalachicola/ Chattahoochee/ Flint (ACF) basin.

The amount of water that flows through the river is controlled by the Army Corps of Engineers. The Apalachicola flows from the Jim Woodruff dam at the confluence of the Flint and Chattahoochee Rivers, both of which originate in Georgia. The Corps also manages the two Georgia rivers with a system of dams and reservoirs.

As you can see on the map, Georgia is currently in a drought. The Water Control Manual for the ACF Basin mandates that under drought conditions, the Corps can restrict flow on the Apalachicola to 5,000 cfs. They reserve that water to feed cotton farms on the Flint and keep drinking water in Atlanta. The rationale is that since the rivers originate in Georgia, the water belongs to them.

The Apalachicola Riverkeeper and other members of the ACF Stakeholders maintain that water belongs to the system as a whole; the Corps should distribute water based on the needs of each component in the system. Furthermore, the ACF Stakeholders maintain that if the Corps better managed its reservoir system, there would be enough water for everyone.

Only Congress can force the Army Corps of Engineers to change their manual. Nonetheless, Governor Scott is taking the state of Georgia to court in an effort to let more water into Florida.

The Apalachicola Bay Estuary and Fresh Water

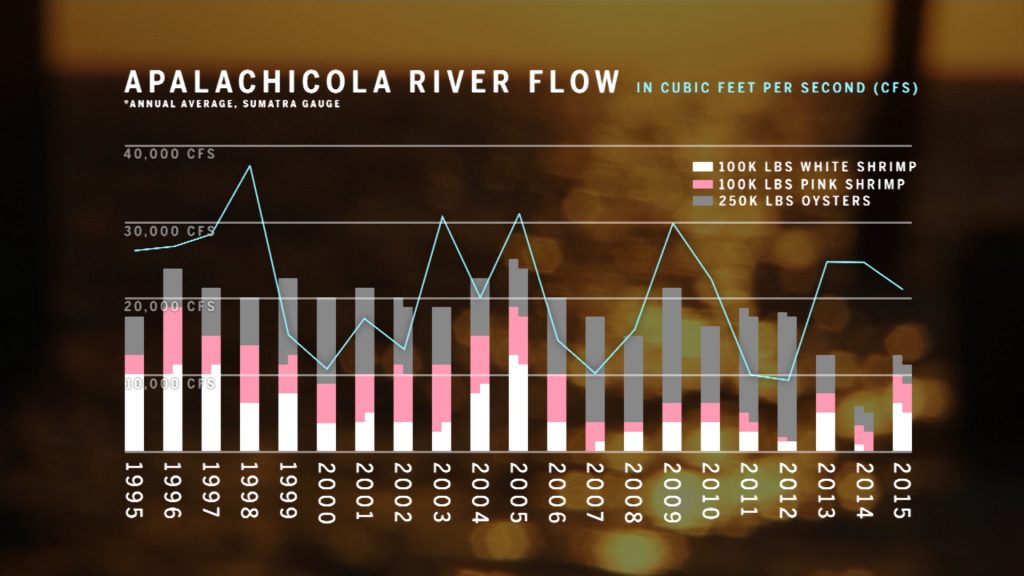

The graph above appears in the video, and it’s worth taking a little time to discuss. It correlates river flow, based on data from the Sumatra gauge, and seafood landings for Franklin County (where Apalachicola Bay is located). Landings data is recorded by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission when seafood workers return from their trips. Landings don’t tell us how many oysters or shrimp are in the water, but it follows that when stocks are lower, there is less product to harvest. This is a rough thumbnail sketch.

Shrimp reach market size within a year. As you see in the graph, an abundance of shrimp reflects the abundance of freshwater flowing from the Apalachicola. Shrimp need the nutrients provided by the river, and if salt marshes in the river delta dry out, it deprives juvenile shrimp of shelter from predators.

Oysters take longer to reach market size- between 18 months and three years. Wet and dry climate cycles last for similar periods, but not always exactly. You can see how some of the highest landings have come in low flow years, and some of the lowest have come during wetter years.

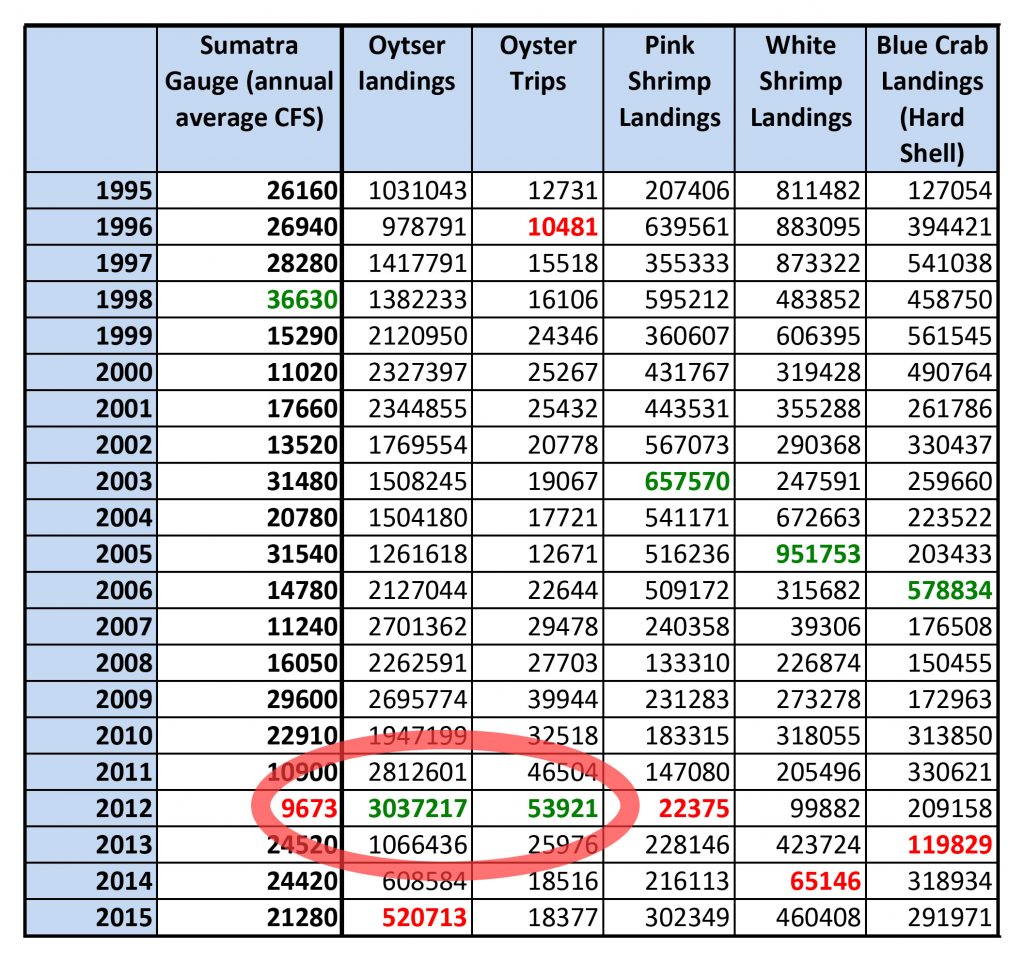

Here are the numbers I used to make the graph. I highlighted the the lowest quantities in each column in red, and the highest in green. I also included a column for the number of trips taken by oystermen. From 2009-2012, the number of trips taken to harvest oysters increased sharply.

The two years with the highest oyster landings, and by far the highest number of trips, were the two driest years on the Apalachicola- 2011 and 2012. The 2010 BP oil spill closed oyster fisheries in Texas and Louisiana, and increased demand for Florida oysters. This coincided with ten months of 5000 cfs flows, which made 2012 the lowest flow year in the recorded history of the Apalachicola.

How did these factors combine to crash the fishery? Is one factor more to blame than another?

What was the exact cause of the Apalachicola oyster fishery crash?

In 2013, the Oyster Recovery Task Force determined overfishing did not cause the crash of the Apalachicola Bay oyster fishery. The way they explained it in a public meeting was this: in previous cases where a stock was overfished, such as Atlantic cod, there was a long gradual decline in stocks, not a sudden collapse. The breeding population of legal-sized adults declines over time, so every generation creates fewer offspring.

The year the Apalachicola oyster fishery crashed, the bay recorded its largest recorded harvest. This means that a lot of oysters were harvested, but that doesn’t tell us exactly what was alive in the bay. However, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services did conduct surveys of reefs in the bay for over thirty years. The Oyster Recovery Task Force incorporated this data into their modeling system, ECOSPACE.

The Task Force noticed that there had been a sharp decline in sublegal oysters in 2012, and determined that mortality was increasing in juvenile oysters. That next generation of oysters never made it to market size and never spawned to create the generation after them.

The available data was insufficient to determine what killed these younger oysters. Fewer nutrients had flowed down the river, and the bay was saltier. Could that have killed the oysters?

This experimental cage allowed access to predators. When David Kimbro’s lab retrieved it from the bay, it was full of southern oyster drills (Stramonita haemastoma) and their egg sacks. Each sack contained about twenty oyster drill larvae.

That next spring, David Kimbro and his crew conducted surveys and experiments in the bay. They noticed a large abundance of oyster predators, specifically crown conchs and oyster drills. They also found that these snails spawn more in saltier waters.

Drills and conchs often prey on younger oysters with softer shells. When David excluded predators from oysters in his experiments, they survived at higher rates than when predators had access to the oysters. So, in the spring of 2013, water quality could be dismissed as a cause of oyster mortality; but by then more water was flowing down the river. The conditions were not the same as in 2012.

The truth is that we have an incomplete picture of the bay before and up to 2012.

FDACS surveys measured the density of oysters, the number of oysters, and the mean length of oysters within .25 meter quadrats. However, they did not measure salinity or oyster recruitment- the number of oyster larvae that settle on reefs. Nor did they record the number of oyster predators.

There is a good bit of suggestive evidence, but no smoking gun.

Improving Our Knowledge of Apalachicola Bay

Shannon Hartsfield started teaming with UF’s Dr. Andy Kane in the months following the fishery collapse. They’ve been conducting more intensive surveys, and looking at a variety of factors:

- Salinity and predator abundance. Flows have been healthy since February 2013. Now that the Apalachicola is experiencing lower discharge, they’ll be able to plot the change in predator numbers as the bay gets saltier.

- Oyster health and salinity. When salinity is higher, there are more predatory snails to eat oysters. However, salinity might also directly affect oyster health. This in turn might make oysters more vulnerable to predation.

- Growth rate. How much faster does an oyster grow when the bay has regular freshwater input?

- How fast does a reef recover after it is harvested? And, do some sections of the bay recover more quickly?

With this information, they’ll know more about how oysters react to different conditions in different parts of the bay. The hope is that this would help FDACS better decide when to open and close parts of the bay, or reduce harvesting.

The fear is that while Florida might be better equipped to manage Apalachicola Bay during future droughts, its oyster reefs might never regain their once-legendary productivity.

Apalachicola Bay | Oystering Heritage in Peril

Shannon Hartsfield is a fourth-generation Apalachicola seafood worker.

Many of my conversations with oystermen and women over the years include some version of a family history in relation to Apalachicola Bay. At the minimum, you’re told a generation. Often, you’ll get stories about working the bay with fathers, grandfathers, and other family members.

“Born and bred. You’re raised in it,” Hartsfield tells us. “I got to fish with my great-granddaddy. He lived to be 97 years old. My granddaddy, he was a shrimper, mostly.”

But the Hartsfield family’s professional connection to Apalachicola Bay is weakening.

“My Brother, he’s oystered over the years, a lot,” Hartsfield says. “Now he’s a corrections officer.”

We met Shawn Hartsfield in 2013 when he helped David Kimbro’s lab conduct research in the bay. On one frustrating trip, he was unable to find two bags of oysters for one of their experiments. In better times, he would have harvested two bags in 45 minutes.

With a lack of product in the bay, oystermen are turning to other jobs.

“A lot more of them is doing truck driving,” Hartsfield says. “A lot of guys are doing things they don’t normally like to do.”

As Smokey Parrish says in the video, there aren’t manufacturing jobs, movie theaters, or Walmarts in Apalachicola. When seafood jobs go, so do seafood workers.

That includes Shannon Hartsfield’s son. “My son started oystering with me and I pushed him elsewhere,” Hartsfield says. “He’s a welder.”

If Apalachicola Bay does recover, it may not reach its previous productivity. And there’s not likely to be a fifth generation of Hartsfields working it.