A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the Henslow’s sparrow, and an ancient (okay, old growth) forest. It’s part one of EcoShakespeare:

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

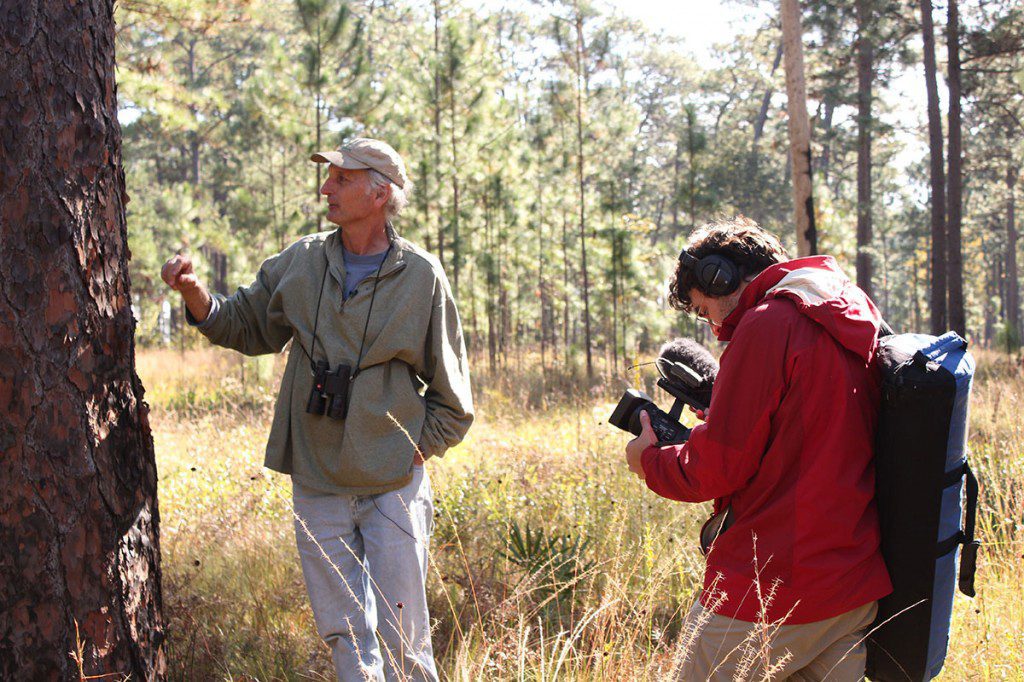

Jim Cox is the Vertebrate Ecology Program Director at Tall Timbers Research Station (he’s the one not holding the camera). Based north of Tallahassee, Tall Timbers has studied the longleaf habitat, and its dependence on fire, for over 50 years.

We begin this EcoShakespeare project, appropriately enough, in a longleaf forest that exists much as it did during the time of William Shakespeare. The “Big Woods,” as Tall Timbers’ Jim Cox calls them, sit on private land. Few people will ever get the privilege to walk under those ancient longleaf pines, in one of the few places where Henslow’s sparrows and red cockaded woodpeckers are relatively easily seen.

And it’s one of the few places where you might find longleaf pines that lived while the Bard’s plays were being penned.

You can see the numbers in the video above. The American southeast was once covered in 90,000,000 acres of longleaf. Today we have 3,000,000. Of that, only 8,000 has never been cut. Jim compares it to the entire population of the Earth being whittled down to a city the size of Milwaukee. And while 3,000,000 acres is still a vast reduction from the historic number, it’s much better than 8,000. So why do we emphasize the especially low acreage of remaining old growth forest?

The immortal king of the fairies, Oberon, stands next to a considerably younger 350 year old (give or take) longleaf pine.

Old trees make better homes for red cockaded woodpeckers (and other species)

It’s something that I can appreciate as I stare down my fortieth birthday next year- a mature longleaf offers more ecosystem services than a young one. Red cockaded woodpeckers make nests in trees that are over 90 years old. The heart wood of these older trees is more likely to suffer from red heart disease, a fungus which softens the wood and makes it easier for the woodpeckers, over several generations, to make a cavity.

Jim Cox, answering questions from our adventurers, says the birds’ numbers are looking much better after getting dangerously low. He attributes this to artificial cavities sawed into less mature trees. But for the RCW to leave the endangered list, it has to make it without our help. And for that, we need more mature trees. The problem with that is that… you have to wait… and wait… and wait… for enough of them to get to that right age.

The Henslow’s Sparrow: A winter visitor to the longleaf forest

For the adventure portion of today’s segment, our participants helped Jim Cox capture and band a rare migratory bird. The Henslow’s sparrow spends the warmer months in open grasslands up north, where it nests. In the winter, it heads south, where its preferred habitat is the longleaf pine forest. Regular burning (2-3 year interval) creates an open, grassy understory between the pines. Grasses and flowers here rely on fire to kill off hardwood trees. You’d be surprised how quickly these plants sprout after a burn.

These grasses are an ideal habitat for the Henslow’s sparrow. As you can imagine after seeing how much longleaf habitat we’ve lost, this bird’s numbers have declined. And so it is a species of concern. By banding it, Jim and other researchers can learn more about the species’ behaviors. The bands are observable through a birding scope or binoculars, and so anyone who spots it can report where they found it, and what it was doing.

Jim lines us all up at one end of a grassy open spaces. Across from us is a thin mist net. As we walk and make noise, we scare up a Henslow’s, which flies into the net.

Jim Cox affixes a numbered metal band to a Henslow’s sparrow’s leg. He will then register the number along with information he gathers about the bird (time caught, weight, wingspan, etc.). The Bird Banding Program is overseen by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service; Jim has to get federal authorization both to band birds and to use a mist net.

By registering this information, he starts a file on this bird, which other researchers and citizen scientists add to when they spot the bird. This way, they can accumulate knowledge both about this individual and about the habits of the species. If the bird is recaptured, someone will see that, indeed, it had a role in a Shakespearean production.

A little more about the Henslow’s sparrow

- The bird’s wing length helps Jim locate its point of origin. Henslow’s from out west tend to have longer wings than their eastern counterparts.

- Henslow’s sparrows keep their weight down before migration. This keeps them from using too much energy during long flights. When they first arrive at their destination, Jim says, they are emaciated. The one in the video had been in the Big Woods for a little while, though.

- The bird usually forages for grass seeds on the forest floor. One type of grass we saw in the Big Woods is Ctenium aromaticum, or toothache grass. The roots of the plant are known to have an anesthetic property. I couldn’t get it to numb my gums. Maybe I had to chew on it some more.

Up Next:

Next week, we look at Shakespeare’s upbringing as we forage for food along Lake Iamonia. Also, marital tensions between Oberon and Titania escalate as the king plots with Puck to use the herbs of the forest against the queen.

Special thanks to WFSU’s partners for this EcoShakespeare segment, The Southern Shakespeare Festival and Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. EcoShakespeare is funded by a grant from WNET’s Shakespeare Uncovered. Catch their take of a Midsummer Night’s Dream Friday, January 30 at 9 pm ET on WFSU-TV. For more information on Shakespeare Uncovered and WFSU’s associated TV and Radio projects, visit our Shakespeare Uncovered web site.

Shakespeare Uncovered is made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Major funding is also provided by The Joseph & Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, Dana and Virginia Randt, the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust, the Lillian Goldman Programming Endowment, The Polonsky Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, Jody and John Arnhold, the Corinthian International Foundation, and PBS.