I recently (May 2022) spoke to the Florida Federation of Garden Clubs about seasonality in bees and native plants. I enjoyed giving the presentation, and I liked the response. So I’m sharing it here.

If you’ve seen any of my other blog posts on bees and pollinator plants, many of the photos will look familiar. What I’ve done here is built a chronology of native plant blooms, and of the bees that visit them. I’ve collected the photos from over a three year period; and from year to year, different bees and different flowers fly and bloom at slightly different times. North Florida seasons can vary, but not wildly. Summer plants are still usually summer plants, even of one year they bloom a couple of weeks later.

What follows is a year in flowers and bees, from season to season. We start as winter turns to spring, and different bee species start to emerge and seek nectar and pollen.

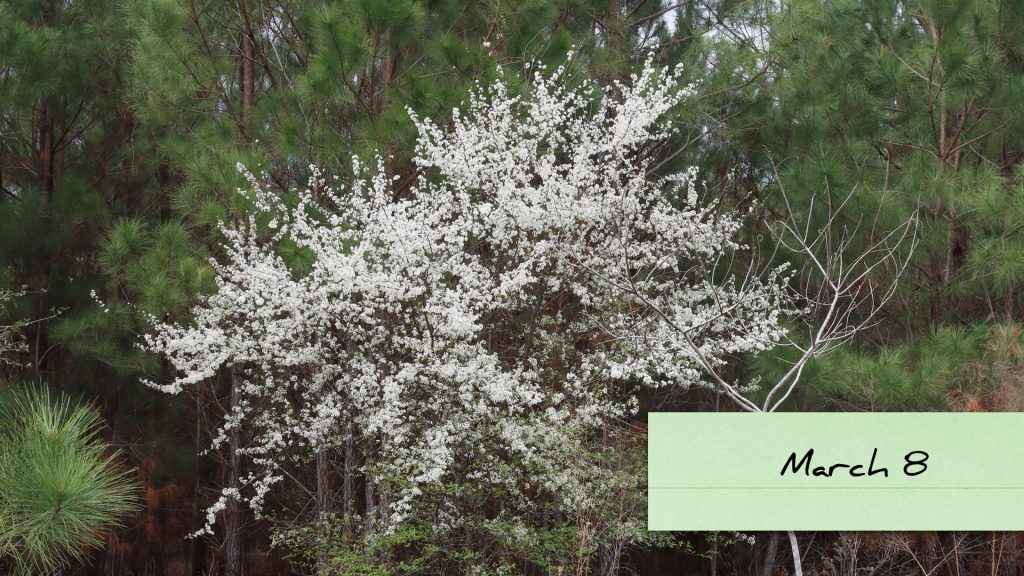

Early March and Mining Bees

I gave the talk as a result of our participation in the My Garden of a Thousand Bees project. For that project, I talked to plant experts about the best plants for bees. I was surprised at the importance of trees and shrubs. Because they bloom earlier in the year than most wildflowers, they feed early pollinators, like this mining bee.

Mining bees are some of the earliest flying bees in our area, and I only ever see them pollinating trees.

This photo is from the Grove Museum, where WFSU had a Bee in My Garden Days event. Fortune smiled on us, as it turned out my station was next to a field of mining bee nests.

Mining bees are solitary ground nesting bees, though hundreds may build nests close to each other. At this spot at the Grove, patchy turf grass gave the bees access to that sweet Orangeburg sandy loam. Because many native bee species are ground nesters, it’s essential that we keep some bare earth in our yards.

In our segment on bee nesting habitat, we talked about mulch. We learned that wood chip mulch can block access to the ground. Instead, we can mimic the natural mulch that covers our north Florida forests. Longleaf pine ecosystems were once the dominant habitat type in the American southeast. As we see in the pine straw mulching a wax myrtle tree at the Grove, it allows bees access to the ground to build their nests.

Other trees for bees

The bee plant list I compiled has many more species, but I featured these two in my presentation:

I saw a couple of these trees near Lake Talquin, and was struck by how choked with flowers they were. I couldn’t get a specific ID from iNaturalist, but this is in the Prunus genus.

More flowers for those early flying bees. Mining bees finish flying in April/ May- they can’t survive without native trees that flower in February/ March. Other bees that fly early, like bumblebees and carpenters, fly for most of the year.

Blueberries and Blueberry Diggers

Blueberries and other native shrubs also flower early in the year. Walking in a longleaf forest in the spring, you’ll notice just how many blueberry bushes there are in the wild. There are six species of Florida native blueberry available in nurseries; rabbiteye is the species humans most enjoy eating.

Here’s a bee I saw all over my yard without a camera in hand. First, I saw it probing the leaf covered ground in a flower bed, then climbing into a hole. I then saw it on blueberry flowers. I finally photographed it after it had successfully pollinated the blueberry bushes and had turned to the betony.

The blueberry digger bee is another ground nester, and another early flyer. Both it and the mining bee return to the ground by mid-spring.

Florida betony is one of a handful of native weedy wildflowers that bloom in the early spring. Another of my favorites is clasping Venus’s looking glass:

Like the mining bee and blueberry digger, small, early blooming wildflowers like these, Florida betony, and Carolina crane’s bill disappear from the yard by the end of spring.

By Mid-April, Tickseeds Bloom

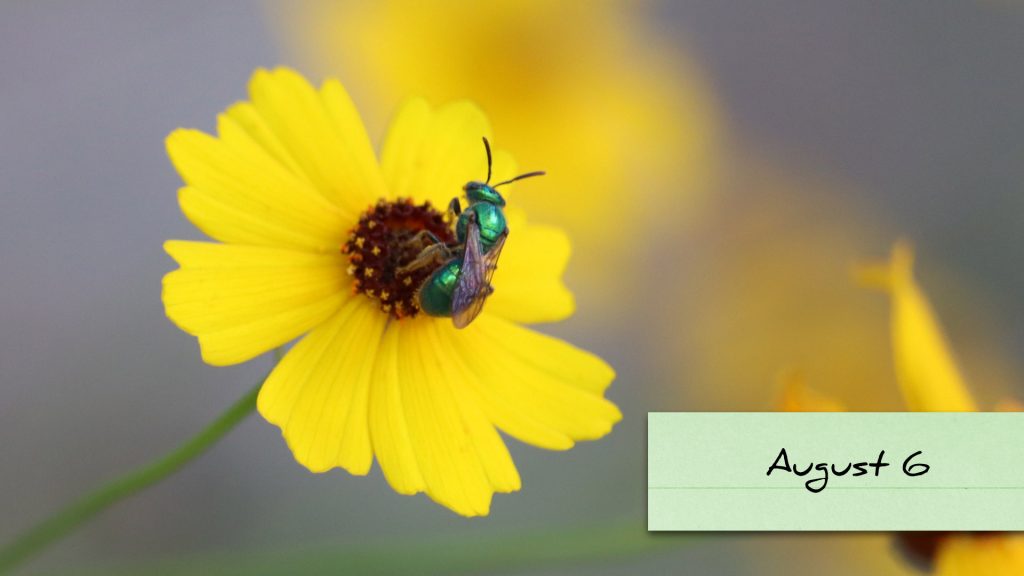

The trees have bloomed and faded, and so also have the small early blooming weeds. Now starts the spring and summer wildflower season, when things really start to pick up. We start to see flower and bee species that will become commonplace until, possibly, as late as fall. Tickseeds, or Coreopsis, become an important nectar source for the next several months.

These photos are from previous years, but right now (May 2022), two species of Coreopsis are exploding in the yard. And with them, I’m starting to see some of our mainstay bee species- in particular, sweat bees. The bee above is a Lasioglossum genus, Dialictus subgenus. There are hundreds of Dialictus bee species in the US- they are small, and not usually easy to distinguish from one another.

Some Dialictus in the yard are slightly larger than the others, but they’re all somewhat ant sized. I like this species of Coreopsis; a couple of years ago I bought a single plant, which has seeded from itself over a dozen more. They produce more and smaller flowers than lance-leaved Coreopsis, which also has reseeded itself over the yard.

Another common sweat bee in our yard, which we’ll see until fall.

And another common sweat bee in the yard.

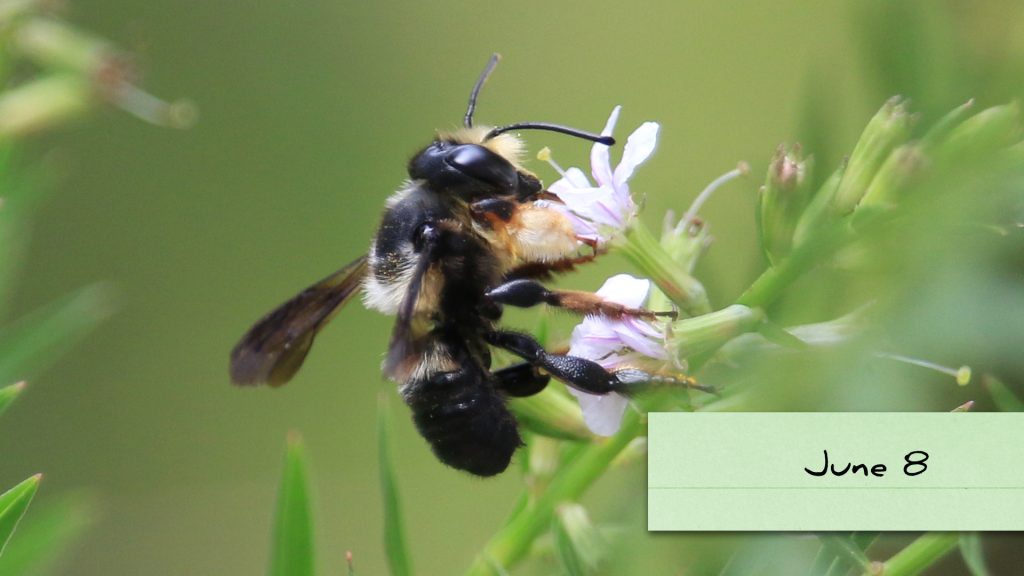

The Two-Spotted Longhorn Bee- a Bee for late Spring/ Early Summer

Here’s a bee I always start to see from mid May until early July or so. It visits several of the flowers in our yard, and regularly visits squash flowers when we grow it. By the end of June, I might see 3-4 of these in the yard at a time. And then their time is done for the year.

I bought two of these plants about four years ago. There are now dozens, and would be more if I let them. A few bee species love these, from the longhorns and bumblebees that hang on them to the Dialictus which walk into the tubular flowers.

Winged Loosestrife

Another popular flower for bees and butterflies from mid-spring and through summer.

This plant attracts bees I never see on any other flower in the yard. This bee visited us for a couple weeks in 2020, and I’ve never seen the species again here. I did see a female carpenter-mimic at Elinor Klapp-Phipps Parks in July of 2020.

Another species of sweat bee, which looks similar to the Augochlorine sweat bee. This has more pronounced stripes on its abdomen. Their males are much more easily distinguished. We don’t see those in our yard until August. I imagine this is a mother bringing home pollen for her brood.

I only ever see this in August, much like the male brown-winged striped sweat bee (Agapostemon splendens). It turns out there’s a reason for that. See how this bee has no pollen sacks? That’s because it doesn’t feed its own young. This specific species of cuckoo bee lays its eggs with bees of the Agapostemon genus. When that brood emerges, so does that bee.

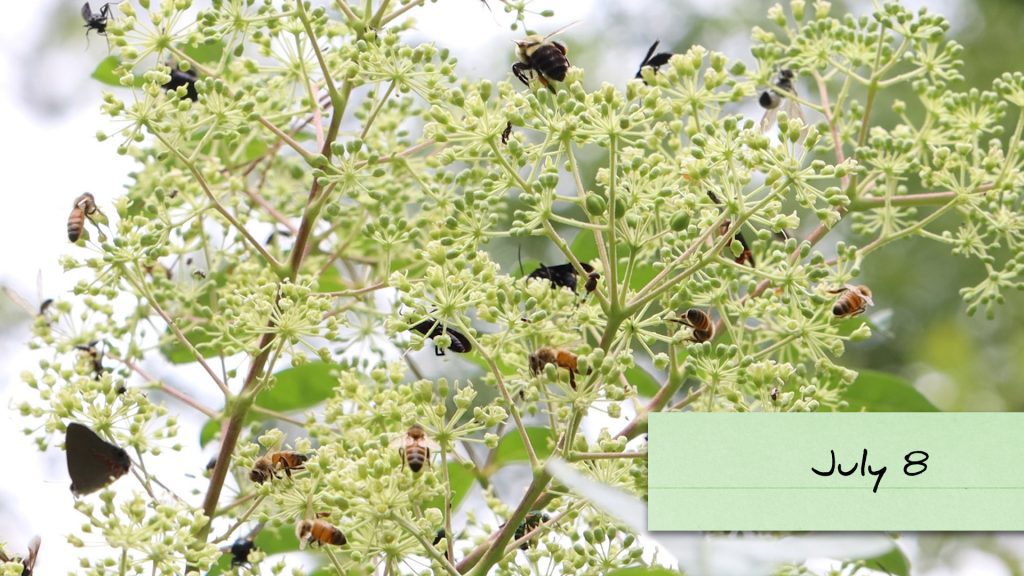

Devil’s Walkingstick- a Short, Intense Summer Bloom

From mid to late summer, we see a handful of plants that have a short blooming window, but which attract swarms of pollinators. This is not in my yard, but in that of Jonathan Lammers, who has shared history knowledge and let me shoot video of his yard from time to time on this blog. Check out the full video and post on devil’s walkingstick, in which I identified about 20 species of pollinator over two visits.

Partridge Pea

Another plant that blooms over summer, and a larval food for cloudless sulphur butterflies.

Rosinweed- A Pollen Bonanza

Look how pollen-covered this furrow bee is. I love shooting video of bees on rosinweed, because they spend so much time working the plant. This is another plant that starts to bloom as spring turns to summer, and throughout the summer.

And here’s the male brown-winged striped sweat bee. After two years of flying from the beginning of August through the very start of September, in 2021, we saw them from mid-August to mid-September. What changed? A colder winter? Did some flowers bloom later? We’ll see what they do in 2022.

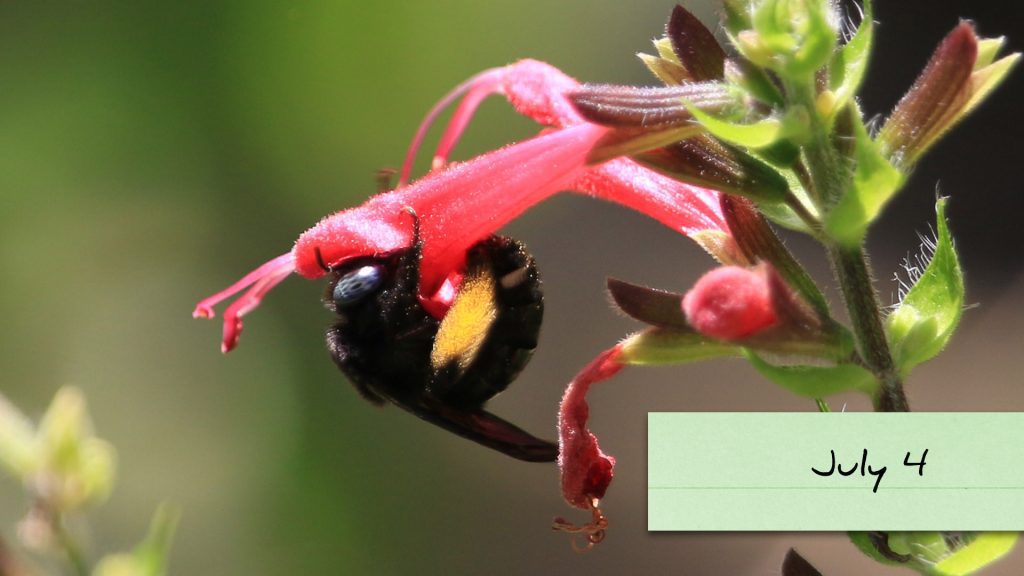

Dotted Horsemint- Another All You Can Eat Pollen and Nectar Buffet

Just as the devil’s walkingstick fades, this is starting to bloom. It attracts many of the same pollinators, namely bees and a good variety solitary nesting wasps. It blooms for a few weeks, during which it is swarmed.

Carpenter bees were the first bees I saw flying in 2022. I see them for most of the year, mostly seeking out their nests in our fenceposts. But I rarely see them on our flowers. This is the one flower I see them consistently visit year in and year out.

Brickellia cordifolia– Beloved by Bees and Monarchs

Just as the beebalm is fading, this is starting to bloom. I had never thought of this specifically as a bee plant. When we started shooting for our My Garden of a Thousand Bees project, I went straight to the beebalm to shoot video. And then I started noticing that, in the evening, bees were crawling all over the Brickellia.

During the day, though, this is what happens on Brickellia:

It was an especially busy year for monarchs on our Brickellia plants. For a couple of weeks, we had up to five at a time sipping nectar. Sometimes, one would get frisky:

It often ended with the female shaking off the male, and getting back to what must be delicious nectar. Sometimes, the male had success:

These two coupled, and flew off conjoined:

The Fall Wildflowers: Elephantopus

Brickellia is a late summer blooming plant. As it fades, so do a lot of our other wildflowers. But there are still plenty of hungry pollinators out there. October through early November is peak wildflower season out in the longleaf forest; as we mimic natural habitat it our yards, we want to include plenty of fall blooming wildflowers.

This is Elephantopus, a small flower in the aster family. For most of the year, it looks like this:

In the late summer/ early fall, it sends up a stalk, finally flowering in the fall. This grows as a weed on many of our lawns, and with its low lying leaves, you can run a mower over it during all the months before it shoots up that stalk.

More Fall Bloomers

There are a few other Florida native sunflowers that bloom for longer, over the warmer months. Despite leaves that are conspicuous throughout the rest of the year, it flowers almost exclusively in October. I started these from seed.

Goldenrod blooms into November. It’s about the last flower to bloom in north Florida, and an important nectar source for monarchs building up energy to migrate across the Gulf of Mexico. You can buy goldenrod in nurseries, and it also grows as a weed in many places.

Blazingstars: A Bonanza for Bees, in the Fall

One Saturday afternoon, I took my son Max out to the Munson Sandhills with one goal: to take photos of bees on fall wildflowers. I took many, and iNaturalized a couple of species new to me. The star of the day was, well, blazingstar. This fall blooming plant is another one of these short bloom window/ high pollinator volume plants.

The previous photos are of some of the common species in my yard, species common to our area. The following is a forest bee:

Here was a bee entirely unfamiliar to me, so I eagerly uploaded photos to iNaturalist. A top bee biologist user of the app identified it as the long faced cellophane bee. Dr. Jon Ascher says it is “Historically overlooked due to late flight season.” Where mining bees and blueberry diggers fly for a short period early in the year, this flies for a short period at the end of the year.

He went on to say that is was a “rarely recorded, localized, and specialized species.” A north/ central Florida endemic, this bee specializes in blazingstars, a late blooming plant.

Fall Asters

Technically speaking, many of the species in this presentation are in the aster family, Asteraceae. More specifically, American asters are the genus Symphyotrichum. In our area, this includes several fall blooming plants.

The one above is rare in our area, but available at nurseries and easy to grow in a yard. This plant bloomed profusely last year, and so I bought a couple more.

This one grows as weed all over my yard. Once you recognize the leaves, you may notice that this has bee growing in your yard throughout the year. If you let it be, it’ll bloom in October and feed late flying pollinators.

A Couple of (Not) Beloved Weeds that can feed Pollinators Almost Year-Round

These next couple of plants, if you do nothing, will grow in your yard. If you’re not careful, they’ll be everywhere. They might overwhelm you. But if you make some space for them, they bloom year-round and are beloved by bees.

I admit that right now, I’m pulling a lot of Bidens alba from my yard. There are places where it’s crowding out other wildflowers. But I’m also letting it grow in a few places. The photo above is one reason why. December was warm last year, and both in my yard and at Klapp-Phipps Park, bumblebees were flying outside their normal season. What was there for them to eat?

Without a hard frost, this plant will bloom in every month of the year. This is important in north Florida, which can have wildly variable winters. When it’s warm, there are always a few pollinators that fly. And they’re hungry.

This is especially true of honeybees, which are not native and have a different seasonal clock than our native bees. They are an important animal when it comes to food production. For this reason, Florida Native Plant Society’s Lilly-Anderson-Messec has said that Bidens Alba is one of the most important plants for honeybees.

Another native wildflower that can take over your yard is Ohio spiderwort. I like this plant in the early spring when it, along with Florida betony and the others I mentioned earlier, fills my yard with nectar in the late winter/ early spring.

A Year of Bees and Flowers

You can see that over the course of a year, I rely on trees, shrubs, planted wildflowers, and weeds to feed a wide variety of bees. I have a small yard, much of it paved, near downtown Tallahassee. Some of you reading this will have more space, and some less. Some will be closer to wooded areas, some in a more urban environment. Different plants will work in different settings.

I encourage you to check out our pages on creating bee habitat, and on the bee species of our area. I add pollinator and garden related content as often as I can; I’m always learning, and so will you be as you start inviting pollinators into your yards with native plants.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.