The following are interviews collected for WFSU’s podcast series, Not so Black and White: a community’s divided history. Excerpts from these interviews were used in an episode about Black land loss, and the decline of Black agriculture. Rob Diaz de Villegas and Robbie Gaffney interviewed residents of historically Black communities in and around Tallahassee.

Both in the city and in the country, Black communities fed themselves with food they grew. As we explore in the podcast, many of these communities have disappeared or have declined, as have the farms and gardens that brought people together.

The following are remembrances of five different communities in and around Tallahassee. Three are from the NSBW podcast interviews, and the other two are from our Roaming the Red Hills (2016) series.

Dr. Sandra Thompson

Dr. Sandra Thompson is an Extension Agent with the Florida A&M University Cooperative Extension. She is focused on issues pertaining to Black land ownership, in particular Heir’s Property. She holds workshops to inform Black landowners of the legal mechanisms surrounding the ownership of land, of their rights and options.

Dr. Thompson is also collaborating with Florida State University on the North Star Legacy Community Project. The project documents what she calls Legacy Communities, Black communities dating back to pre-Emancipation plantations, or founded shorty after Emancipation. Many of these communities stayed together into the twentieth century, and a few are still active today.

What is a Legacy Community?

In that they started, most of them, pre-emancipation, during slavery, one of the things is that in order to survive the conditions of slavery, you had to organize yourself in a way that you could take care of yourself, your family, and those you love.

Growing up in Barrow Hill

Sandra Thompson grew up in Barrow Hill, a legacy community in eastern Leon County. She shares details from her experiences there that show what life was like in a legacy community.

The institutions and the knowledge that was transferred over generations. One of the things my grandma, when you got a cold, she would go out and get these different roots and different kinds of leaves and make this tea. So, my brother is quite ill right now, where he at 60 remembers what his grandma did. “Oh, you all need to go and make me the tea Grandma and we used to make.” You know what I mean?

One of the things is very few people didn’t maintain a garden, some chickens, few hogs, maybe a cow or two. Some had larger if they really made a living from that, the land. My grandfather died in 1958, so we had, I think probably about initially 13 acres and then three were given to people or sold. And so my grandmother couldn’t manage that land. So she would let a gentleman from Rock Hill, the legacy community to the north of us, the farm on the land at no cost, just. And he grew peas and corn and all different kinds of vegetables. And that was the way of sharing and bartering in the sense that you’ve got all this land you can farm at no cost, but it helped manage the land, keep it so it didn’t grow up. And you get to benefit from some of the vegetables that are grown.

Crime was non-existent because if you did something before you got home with people who had who were tenant farmers, who came out of that tenant farmer history, had ways of communicating with each other about their children and about what was going on.

Miaisha Mitchell

Miaisha Mitchell is the Executive Director of the Greater Frenchtown Revitalization Council. One project in which the Council was involved was the creation of the iGrow Garden on Dent Street. The garden returns Mitchell to her roots growing up in Smokey Hollow, a Black community near downtown Tallahassee. In the early 1960s, the state of Florida exercised eminent domain and forced the residents of Smokey Hollow from their homes to make way for a complex of state government buildings.

Growing Food in Smokey Hollow

In Smokey Hollow, we had food. We had food all the time. Never, never was an issue of hunger, per se, because everybody had gardens, you know, everybody had even raised bed gardens, container gardens. They had gardens inside of their windowsills in the kitchen. To grow the small herbs, for medicinal purposes and also for seasonings and things of that nature.

Everything we had was food that we could collect and we had lots of fruit trees throughout Smokey Hollow. Because that community was so tight knit, we had people coming in and out in different gardens along the row in the quarters that we lived. So different people grew different things. We had a lot of collard greens, a lot of the greens because that’s what people ate a lot of- onions, you know, some sweet potatoes, for sure.

Our next door neighbors had food. They would grow peppers and things of that nature, lots of okra. The things that people like, the staples that people enjoyed pretty much.

Learning from family in the country

Some of our family members lived in the country. So we would go out either down to Wakulla, or Crawfordville, or down to Bradfordville and Chaires. And we would go and learn how to do all the things we brought back to Smokey Hollow.

We had to pick corn. You know, we had to shuck all that. We had to get it ready to go to the market. We had to pick the string beans and peas. We had to shell those peas and package them and get ‘em ready for the curb market on Saturdays. So every single thing that we learned at those farms that our family members had in a community, we learned and put it back to Smokey Hollow.

The end of Smokey Hollow

People leaving the traditional home changed a lot of that, you know, for us. Throughout the country, there’s a lot of movement, a lot of urban renewal and eminent domain and all that type of thing happening.

In the late sixties and early seventies, people were just displaced. And when you go to other people’s houses and live with other folk, you don’t have the same type of opportunities to grow food, they don’t have the same type of values.

And you’ll have to leave town and not have access to the country anymore. You know, where you learn to do those things and when you don’t have your family members who live with you all those years able to come back and live in public housing, that’s tough. Because in public housing, they don’t necessarily want you to bring any other people with you. And all you can bring is your nuclear family. You know, mom and dad and the children. But your cousins and aunties and grandmamas and all those you couldn’t bring them. And it was just hard.

So I think a lot of it had to do with the changing scenario of the landscape. You know, around the late sixties and the early seventies, we started seeing changes happening, and a lot of the change took out businesses. And so we didn’t have access to the groceries any more.

You know, here in Frenchtown, they had lots of grocery stores, six or seven. And over in Tallahassee, east Tallahassee, what you call Smokey Hollow, now Cascades Park, we had five, at least, grocery stores in the area, plus we had a curb market where people would come and bring fresh fruits and vegetables.

So those things are not happening anymore.

Ann Roberts

Ann Roberts is a historian and author who has lived her whole life in Tallahassee’s Frenchtown neighborhood. In her lifetime, she has seen considerable change in the neighborhood. She starts by describing her childhood during segregation.

Everybody had a garden. My Aunt Edie right behind me had a garden. When my mother was a child, they had a big garden in the back. Plus they own the land across the street where the pear orchard was. So they had vegetable gardens over there.

Everybody had a garden. If they didn’t have one in their yard, they could get it from the relatives in the rural area. And people prided themselves on the gardens. How neat the rows are. How colorful it was.

The various colors. Tomatoes. They were different kind of tomatoes. The peas would run up the fence. Everybody’s little plot of land was fenced off. Yeah. We had little wire fences in front and in the back here. Somebody would come and say, Well, this sure is pretty, and I’d be wondering, “Pretty? They’re talking about a garden.”

But then, as I have grown up, I, of course, know the beauty of it. And daddy had an artistic eye, and he would make sure that the red was next to the green, next to the yellows and stuff.

Then you had people with much larger land. The crops were out there.

Strawberries and blackberry doobie

Our favorite person was an old man who had a crooked neck. He couldn’t turn his neck, but so far, so he had to turn his whole body. And he had a mule. That mule would come into town with the most delicious blackberries and strawberries. And my mother… We knew when the blackberries came in, we were going to have blackberry doobie.

They always let us eat the strawberries. The strawberries were so good. You could eat them sometimes. You could put them in milk or cream. But we ate those fresh. The kids, that was always our treat. All five of us those strawberries.

The end of segregation and the decline of Frenchtown

In the very late fifties and the sixties, there was no equality. Even though folk like to say separate but equal, it was no equality. We didn’t know how well off we were living separate. Sometimes I wish it had continued.

Times changed. People were earning more money. Goods were more accessible. And they became desegregated. So, slowly, people began to leave the areas. The areas like Frenchtown.

And we had people who were educators at both the universities. We had high school principals. We had a slew of teachers. So once the area became desegregated, we had folk who moved out.

But after the people came into the area with the drugs in the in the in the late sixties, everybody who wanted to get out and could get out, they did so.

And a few of us are still here. I think I’m the only one who lives in the same house they were born in.

When families moved out, if they owned their houses, some were able to sell them. Some were not.

So what happens is they rented them. Out of state people treated them any way they wanted, the houses. Some of them end up falling down. I became infested with squatters or the drug folk. Now there’s always the exception.

Some people came in glad to find a house in that condition and moved in. But in this area, if you leave this house long, the bugs come in too. So it didn’t stand very long.

The end of Frenchtown’s grocery stores

When the integration started, we felt free to go into the stores downtown. To A&P, the Winn-Dixie. We could go there much more freely. You didn’t go to those stores because you were uncomfortable in them. But once the area became desegregated, you could go and feel much better.

And they had a much larger array of goods than the small corner stores here. You could even go down and get your coffee from A&P, have it ground. And my mother declared it was some of the best coffee around.

So people moved out of the area. You didn’t have to walk right to the store. You got in your cars, because once you moved out, you got the car and everything, and you could go to other stores. So, stores slowly declined in the area. They couldn’t compete with the stores downtown or elsewhere. The stores on Adams and Tennessee and the last grocery store really probably do the seventies. So we had grocery stores up until then.

Eluster Richardson: growing up on Ayavalla Plantation

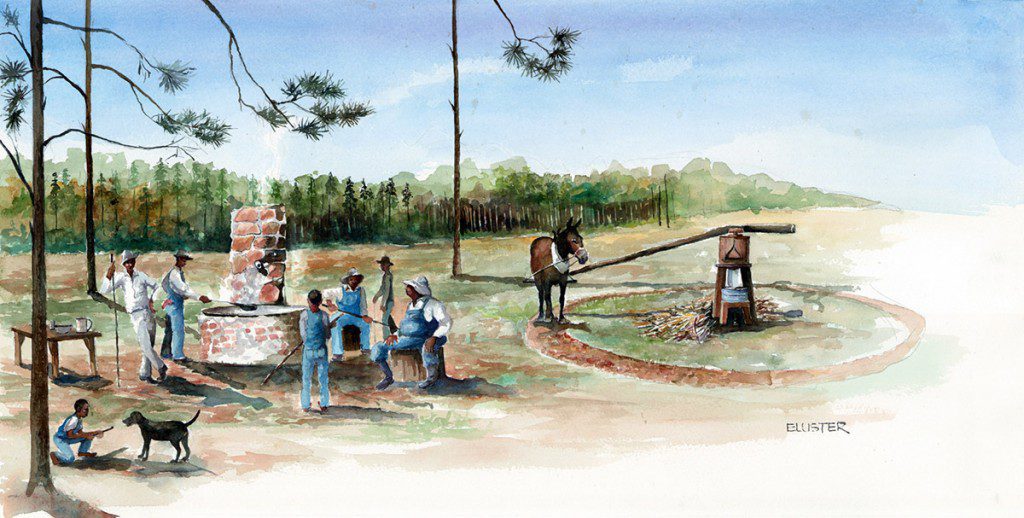

We met Eluster Richardson in our Roaming the Red Hills series. Richardson grew up on a tenant farm on Ayavalla Plantation, which after the Civil War became a Red Hills quail hunting plantation. He depicted scenes from his childhood for an exhibit on tenant farms on Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy, which itself was once a quail hunting plantation that housed tenant farms.

Dr. Flossie Byrd: Growing up in the Junious Hill community

In 1940, Flossie Byrd’s family moved to a small community near the north shore of Lake Miccosukee in Jefferson County. The community was founded in the late 1800’s around the Junious Hill Missionary Baptist Church. In her book, Echoes of a Quieter Time, as in the video below, she remembers life in this small agricultural community.

Dr. Byrd was an educator, retiring as provost of Prairie View A&M University in Texas. Many of the memories she shares are of her schooling at the church’s schoolhouse.