Let’s start with a couple of seasonal indicators. First, a flower that first showed up more or less one year, to the day, after Hurricane Hermine:

Looking back at last year’s Backyard Blog, this year’s bloom is a couple of weeks behind last year’s. But it blooms from the same spot, from a bulb in the ground in front of our camellias. They aren’t native plants, but they are crowd pleasers wherever they randomly pop up.

Love bugs aren’t always crowd pleasers at this time of year, especially on highways. According to UF/IFAS, they breed twice a year, during May and September. This is when you’ll see adults. Like many insects, they only survive for a few weeks in their mature form. For most of the year, love bugs are dead-grass eating larvae, breaking down plant matter and helping to build soil.

Our last glorious batch of monarch caterpillars (and their mysterious demise)

At this time of year, towards the end of the monarch butterfly’s northern migration, we had our largest explosion of caterpillars for 2019. The milkweed plants had all recently regrown their leaves from the last couple of batches, and they’d been looking clean and smooth. It’s a kind of reset for the plants when it happens this way. And when they’re like this, it’s easy to spot little holes in the leaves.

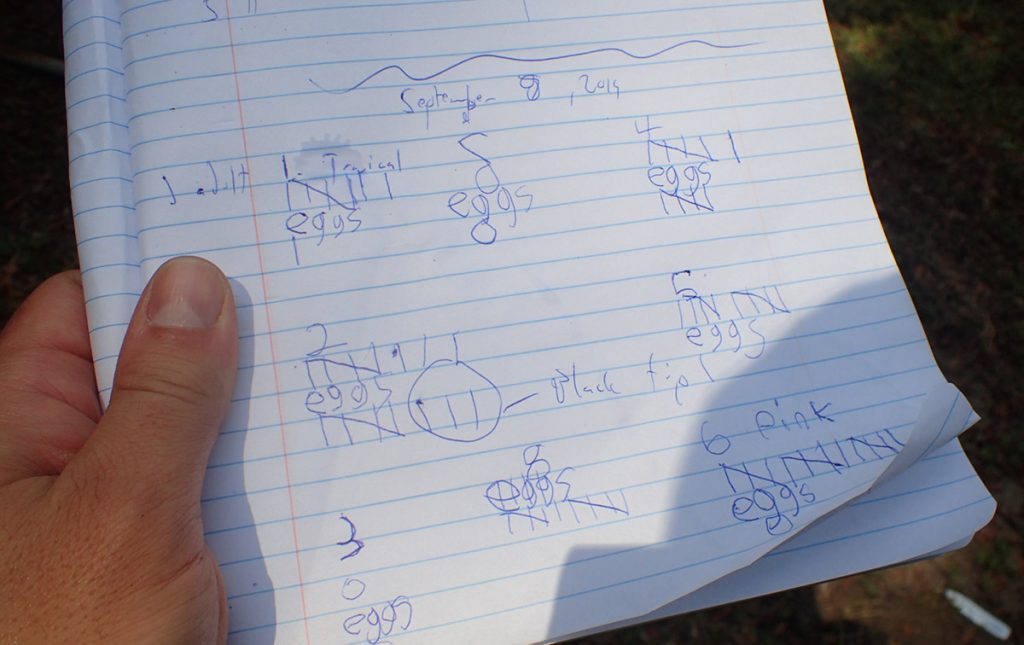

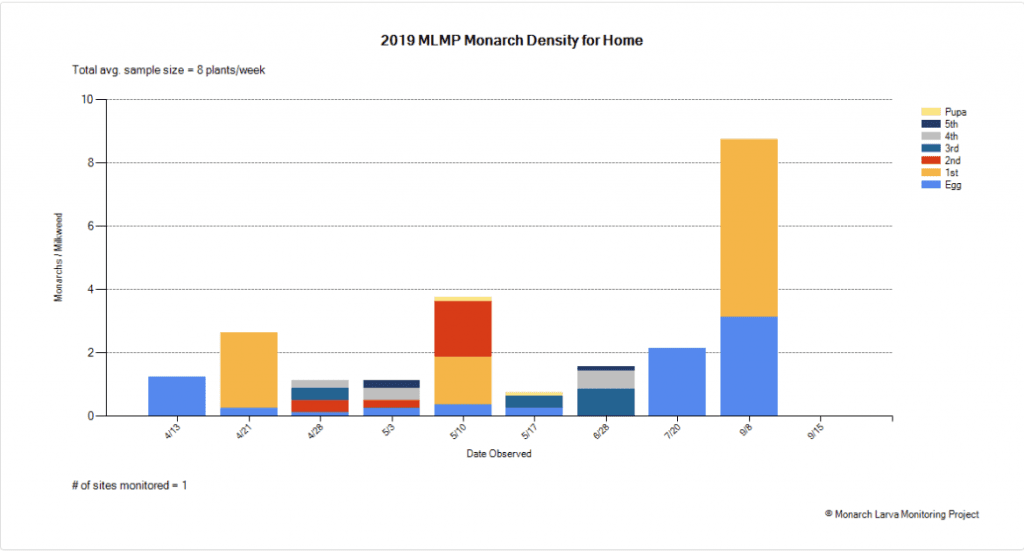

I had a little time, so I thought I’d gather data for the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project. And since my son Max has been talking a lot lately about becoming a “monkey scientist,” I thought I’d get him to help me with data collection. Caterpillars aren’t primates, but observation is observation, and any scientist needs to learn to observe and record what they see.

We had eight total plants then. Six were tropical milkweed (Asclepias currassavica), one was aquatic milkweed (Asclepias perennis), and I had recently bought one pink swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). I didn’t count a second aquatic milkweed plant that had no leaves, but on which they later grew back.

I counted a total of 45 first instar (newly hatched) caterpillars and 25 eggs. That’s more than the plants could support, assuming most of them grew to fifth instars.

Many of the caterpillars were recently hatched, right next to their eggs. It made it kind of hard to count the eggs, actually, though hatched eggs are translucent. And below- are these hatched with a little bit of monarch yolk left over? Are these dead? What am I seeing here?

Not that I expect all of them to survive.

In fact, some of the many dangers facing these small larvae were on display:

I like spiders, and I don’t kill them. But I don’t let them stay near caterpillars, either.

Eep. Max wanted me to try and save this caterpillar. We hate to think of monarchs as part of the food web, but they are. And wasps, in feeding their caterpillar-eating young, also go after cutworms and other “garden pests.” I put that in quotes for the reason I repeat often on the blog. The butterfly caterpillars we try to attract by buying specific plants, and the moth caterpillars that eat our food plants, they’re all just plant consumers.

And by having a variety of plants, we have a variety of insects for birds, spiders, and other predators to eat. It minimizes the catastrophes for the species we like, anyway.

And, as Max said, that’s why butterflies lay so many eggs. It’s an r-selective reproduction strategy. Essentially, if you lay 50 eggs, and only two survive, then you’ve replaced the parents. That makes a stable population. With their numbers having declined so much over the decades, we of course want a positive gain for the species. I think, over the summer, and the last few years, we’ve achieved that in our yard. Just not, as it turns out, with this batch of caterpillars.

We went out of town the following weekend.

Before we left, I bought a couple of milkweed plants, noticing how big the caterpillars were getting. Despite the fact that a lot of them seemed to have hatched at the same time, we were seeing a range of instars. I’ve noticed when food is limited, some caterpillars outcompete the others and grow faster.

Placing the two new plants with the rest, we left for two days. When we got back, all but one of the new plants was completely denuded, and the caterpillars had all disappeared.

We were already into our weeks long drought, and many of our plants looked sorry after two waterless days. Many of our other plants are in pots, and the ones in the ground are in full sun, and are in spots where we’re rehabilitating the soil after they’d been under pavers for well over a decade. Better soil retains moisture better, and makes plants more resilient.

I don’t think this affected the caterpillars, though. And they hadn’t quite run out of food, which begs the question- why was that one plant left intact? It’s not as if it was sampled and deemed undesirable in some way. They just never went to it.

With so many caterpillars, I wouldn’t think their ordinary predators would eat all of them in so short a time. When they get past their first instar, they’ve eaten enough milkweed to be toxic. Bigger caterpillars are safer.

It’s mysteries like these that keep me paying attention, and photographing, our monarchs year after year.

Hidden in the Vines- Part 2

A couple of weeks later, I was sitting on the porch talking to a guest when I looked over and saw the dead chrysalis above. How long it had been there? Last month, I found a monarch hanging from its chrysalis under vines on the other side of the fence. Again, here’s evidence that they’ve been finding places good to hide. This is my first time with milkweed in this part of the yard, and I kept seeing large caterpillars but no chrysalides.

So, on the one hand, we see that this area has good shelter. And yet, this is also the first dead chrysalis I’ve seen this year, perhaps of OE? Like I said earlier, this was towards the end of the northern migration, during which monarchs breed every few weeks. In previous years, I’ve noticed mortality increase after summer ends, including a final batch in 2016 that was all dead, OE chrysalides.

I found this research paper on OE which found that more butterflies died from OE as the summer breeding season progressed, and that mortality “peaked at approximately 15% at the end of the season” for butterflies with OE.

Pollinators: A Quick Look

I didn’t see any new pollinators in September. Part of that might have been that we were in a drought throughout the month. Flowers that bloomed profusely in August withered and turned brown, and their leaves drooped even when watered twice a day. It ended up looking a little sad in the yard.

Anyhow, I took a few photos earlier in the month when the flowers still had something to give.

Identifying Plants in the Yard

As the drought took plants I liked (if only temporarily, as we’ll see in October), a few new hardy weeds popped up. Might I like them, too? First, I’d need to find out what they were:

A flower of the Malvaceae family, possibly in the genus Corchorus.

A flower of the Malvaceae family, possibly in the genus Corchorus.

This was growing out of a crack in the pavement in the backyard. My initial iNaturalist guess is that this is in the genus Corchorus, which has been identified throughout the tropics and subtropical regions.

As the name implies, the old world diamond flower is nonnative. I Googled it, and found a few pages with advice on managing it as a pest. Apparently, it can spread and take an area over with a thick, dense mat. Bye!

The leaves of common elephant’s foot (Elephantopus tomentosus).

Common elephant’s foot buds.

Now here’s something I can get behind. A native wildflower growing along the fence- common elephant’s foot. Check out those huge basal leaves.

Identifying Animals in the Yard

This one actually made it into my bedroom:

An agricultural pest imported from the Caribbean.. no, no, no.

I don’t typically worry about any stink bug, or other “pest” insect species, unless I see them in large numbers. So I let these be.

The first iNaturalist suggestion for these was Spartocera fusca, an adult of which I saw on this plant for a few days last month. Many stink bugs, leaf footed bugs, and other related species have similar looking red nymphs.

As I was shooting our two part story on live oaks, fall webworms were the most caterpillar I saw crawling across their bark.

A friend showed me a photo of one of these geckos and asked if I knew the species. So I iNaturalized one I found in our compost bin. It’s a nonnative species.

So, that was September. In October, it rains again, and our plants respond.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.