In May, we saw flowers and pollinators become more active, I got a great look at a monarch laying eggs, and we use iNaturalist to tell us what’s what among our yard’s plants and animals.

Pollinators Part 1- Butterflies and Moths

Here we have a clouded skipper (Lerema accius) on purple salvia flower. Aside from monarchs who pass through to dump a load of eggs on our milkweed, most of the butterflies we’re seeing are the smaller skippers and duskywings. After last year’s colder winter, we didn’t see zebra longwings and gulf fritillaries all that much in 2018. They, along with long-tailed skippers, were the most conspicuous butterflies in previous years.

Something to keep an eye on.

But since I started the Backyard Blog, I have been paying closer attention and noticing many other butterfly species. Doing yard work, I turn my head for any little bit of movement in my periphery. And I’m paying close attention to flowers. That’s how I see little guys like the fiery skipper (Hylephila phyleus).

Skippers appear moth-like. They’re smaller and funkier looking than swallowtails, which I like. And I like moths, too:

I saw this giant leopard moth crawling across the yard one night. A fascinating looking caterpillar. And from photos, I know the moth looks cool, too, though I still haven’t seen one. They keep laying eggs in my yard, so they have to be around sometime, right?

I’m happy to see the little patch of wildflowers I planted taking off this spring. I’m starting to see butterflies, bees, and pollinating hoverflies buzzing around more and more frequently.

Pollinators Part 1- Bees and Wasps

I planted a few different flowers in that patch, but not all have resprouted this spring. However, the red salvia, winged loosestrife, and purple coneflowers are starting to flower like crazy.

Don’t you love the pollen on that bee? According to iNaturalist, this is a furrowing bee. To me, it looked closer to a ligated furrowing bee than a Poey’s. But geographically, Poey’s made more sense.

I see carpenter bees in the yard yearly. Mostly, though, they din’t stop flying long enough to photograph. This one seemed stunned, or perhaps hurt.

Another common site in the yard is the cuckoo wasp. The name comes from the wasp laying its eggs in the nests of other species of wasp. And wouldn’t you know, this wasp is always flying in and out of a hole where a four-tooth mason wasp seems to live.

Monarch Larva Monitoring and Fun Photo Opportunities

On the morning of May 19, I looked out my kitchen window and found this:

Of course, I’d seen that the chrysalis had gone transparent the day before. Monarchs had been going strong in the yard, but there was one problem. They’d get to their fifth instar, the last stage before their metamorphosis, and then I wouldn’t see them. Was something eating these larger, more full of toxic milkweed caterpillars, and leaving the smaller ones alone?

That’s the theme for our monarchs in 2019. My hope is that they’re getting better at finding hidden spots to make chrysalides. The one above is on the other side of a fence from the milkweed. If you look closely, you can see the stem from one of last year’s chrysalides. I found another chrysalis under a hydrangea leaf.

For not the first time, on a day where we have one monarch eclose, we see another oviposit. Ha ha, sorry, I like these butterfly words. Eclose means to hatch from the chrysalis, and oviposit means to lay eggs. I’ve seen monarchs oviposit before, but I’ve never actually seen the egg like this before:

Here’s an enlarged look at the ovipositor and egg:

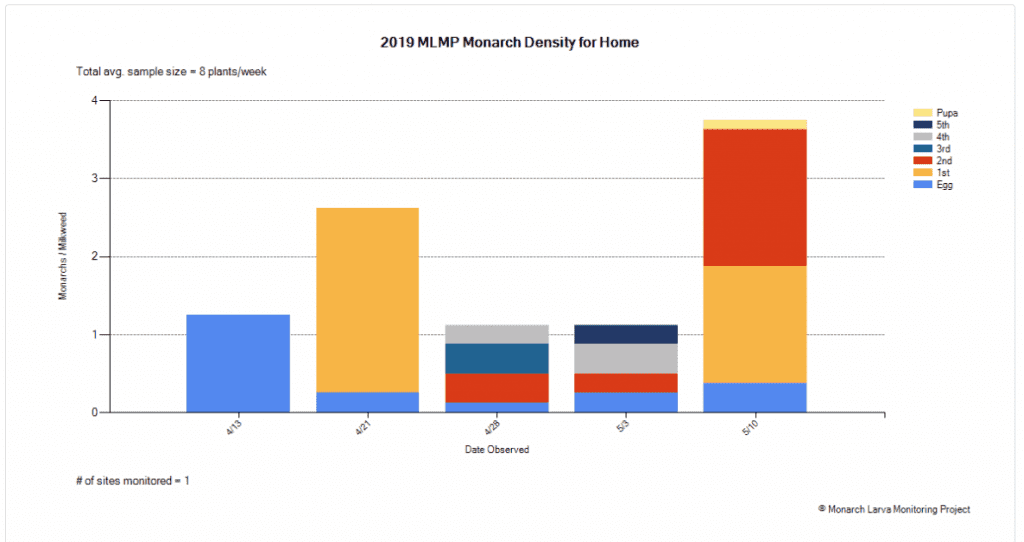

I’ve been dutifully monitoring monarchs in the yard, and entering data for the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project. I go plant by plant and count eggs and caterpillars, and mark their instar stage.

I’ve been dutifully monitoring monarchs in the yard, and entering data for the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project. I go plant by plant and count eggs and caterpillars, and mark their instar stage.

If I have trouble telling the instar stage, the site has a larva ID guide. Additionally, if you ever want to see the complete life cycles of monarchs, black swallowtails, giant swallowtails, and long-tailed skippers, I have a page for you here on the blog.

You can mark eggs, chrysalids, and all five instar stages of caterpillar. You can also mark whether an egg or caterpillar is dead:

It’s not the bright white of a live egg. Just before they hatch, they go transparent and get darker. But this is brown and splotchy, not unlike a chrysalis with OE, the deadly monarch disease. I marked it dead.

My favorite thing about entering data on MLMP is that they make you a graph showing milkweed density in your yard. I have 8 plants, so they divide my total by 8. So when you look at the graph, every line is 8 monarchs:

Random Critter ID

Many stink bugs are, of course, pest species. But some aren’t, and iNaturalist can be a handy tool to tell one from the other. The app doesn’t tell you if it’s a pest or if it’s beneficial, so you then have to look it up. This isn’t a good one.

You might point out that by the time you look it up, it’ll be gone. But I’ve been known to keep an insect in a glass bowl and bring it in the house for better observation. I pretend it amuses my wife. Anyhow, black stink bugs aren’t known to be harmful to plants.

And here’s a ladybug, a beneficial insect, right? For the most part, yes. This is an Asian lady beetle, and if you look at last month’s Backyard Blog, you can see this one is a different color. They vary in their appearance. And, as the name implies, they’re not native. They were introduced by the USDA as an agricultural control in the 1960s. And then their numbers got pout of control.

I’ve noticed these in the house before, and this is where, in some areas, they’ve become a pest. They invade buildings as they prepare to overwinter.

And here I have a mysterious insect next to some monarch eggs. The best I could get on iNaturalist was that it was a green trig, a type of cricket. Crickets are omnivorous, and so even if I wasn’t sure if this was a threat to the eggs, I ran it off.

Another non-native, the asian tramp snail. When I start iNaturalizing every little plant and animal, it can be disheartening to see how many species are nonnative. But these species usually do better in disturbed areas, like where we’ve removed habitat and built homes.

Plant ID

In March, I identified a nearly similar plant as Carolina desert-chicory (named after the many deserts of the Carolinas). So why did I ID this one as false dandelion?

Both plants are in the same genus, have nearly identical flowers- but their leaves are different. This is why it pays to take multiple photos for iNaturalist. For most flowers. No one ever IDs these species, so I looked them up outside of the app. At the very least, the app makes a good starting point for research.

Both plants are in the same genus, have nearly identical flowers- but their leaves are different. This is why it pays to take multiple photos for iNaturalist. For most flowers. No one ever IDs these species, so I looked them up outside of the app. At the very least, the app makes a good starting point for research.

The flower of this plant looks similar to spiderwort, but the leaves and stem are different. iNaturalist recognized it as a dayflower, and based on the leaves I chose climbing dayflower. No one has confirmed this yet.

In this case I may have discovered something highly invasive. This is small and has no flowers, but iNaturalist recommended the Albizia genus. This is likely Persian Silk Tree- Albizia julibrissin, an invasive tree that, once you know what it looks like, you see everywhere.

Above is a photo I snapped at Piney Z. Lake around the same time I found that Albizia in my yard. This tree is flowering at this time of year, which is when I started noticing how widespread this non-native plant is. In fact when we took our vacation in early June, I noticed these pink tufts all along the highway until we got to Texas.

Oak Gall Wasps

You may have an oak tree on your yard, and every once in a while you notice brown bumps on the undersides of leaves. Or a kind of strange knobbiness at the base of leaves, or any number of odd looking structures. You’re looking at the nurseries of gall wasps. This family of wasps has 800 species in North America, and while their galls come in all shapes and sizes, the principle is the same.

Mother gall wasp lays eggs on an oak tree. The tree treats the eggs as a parasite, and its wood or its leaf grows around the eggs. The wasp larvae feed on this structure until they’re mature, eating a little hole through which they fly out.

Here’s a typical gall I found on our laurel oak this May:

This May I also started seeing a kind of gall I’d not seen before:

You can see where the wasp exited the gall. I was seeing quite a few of these translucent galls, in various states:

This appears to be a species known as the translucent gall wasp, Amphibolips nubilipennis.

This appears to be a species known as the translucent gall wasp, Amphibolips nubilipennis.

Apps and Citizen Science mentioned in the Backyard Blog

iNaturalist

Identify plants, animals, lichens, and fungi in your yard. Other users correct your identifications if you’re wrong, and even if they don’t, it can be a good springboard to further research.

Seek by iNaturalist

Instant identification, and it doesn’t record your location. This is a good option for kids with phones.

Monarch Larva Monitoring Project

Enter information about monarch caterpillars in your yard, and help researchers get a sense of the health of the monarch population that year, and how and when they’re migrating.

Great Sunflower Project

Record the number of pollinators visiting your flowers, and help researchers map pollinator activity across the country.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.