In early November, WFSU-TV aired a segment titled “Amateur Archeologist vs. Looter: A Matter of Context?” The video featured proponents of a program resembling the defunct Isolated Finds, which let avocational (amateur) archeologists purchase a permit to collect artifacts that had eroded into waterways from their sites. Since the piece aired, new legislation has been introduced into the Florida House and Senate which would enact such a program. In the video below, we talk to professional archeologists and an avocational opposed to rebooting the Isolated Finds program, including the man who oversaw its previous incarnation.

This segment aired on WFSU-TV’s Local Routes on February 4.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

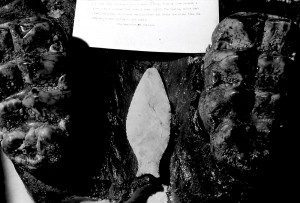

A Simpson point found in Wakulla Springs State Park. Such points have been dated between 8 – 9,000 years old, and have been found locally in the Wacissa and Aucilla Rivers. Photo provided by Dr. James Dunbar.

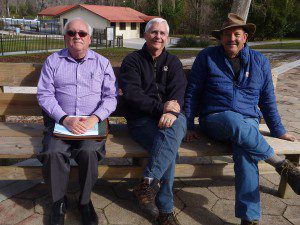

“We’re not in the artifact collecting business,” says Dr. Glen Doran. “We’re in the information collecting business.” To Dr. Doran and the two men seated next to him, a well preserved paleolithic spear point is a puzzle piece, just like the seeds, bone fragments, and chert flakes around where the point was found. While it might be exciting to be the first person to hold it in several thousand years, to archeologists, the story of that tool’s creator is more exciting. New bills would allow Florida citizens to take and keep artifacts found underwater and “out-of-context,” that is, not buried in an archeological site. If passed, Doran and his associates fear an ensuing “gold rush” that would decimate the state’s rich historic and prehistoric resources.

We’re sitting in Wakulla Springs State Park, which contains a layer cake of a site; overlapping levels feature Spanish era Seminoles and a paleolithic site that could be more than 14,000 years old. This and the Page-Ladson site on the Aucilla River are the oldest in Florida, a state whose abundant water preserves a heritage that is clarifying our understanding of North America’s earliest inhabitants. Water not only preserves the stone tools craved by collectors and researchers alike, but also organic material containing information on climate, vegetation, and habitat. Dr. James Dunbar shakes his head. “Why do we just want to let somebody go out there with tools* and dig them out of the bottom of the river?” *HB 803 specifies that hand tools are allowed to be used to remove partially exposed implements.

In the early 1990s, Dr. Dunbar was in favor of creating the first Isolated Finds Program, which was implemented in 1994 and terminated in 2005. While overseeing the program as a state archeologist, he soured on it as he found a majority of participants to be noncompliant. “I came up with something I called Postcards From the Road- not to steal from you guys.” (Classic WFSU-TV shout out!) He sent postcards to game wardens across Florida with an instruction to keep an eye on divers with Isolated Finds permits. His informal polling found that 73% of the participants seen to have collected artifacts did not report them.

More troubling was an increase in looting. “Unfortunately,” Dunbar laments, “people were going beyond surface collecting. They were digging.” In our previous video on Isolated Finds, Teben Pyles and Harley Means evoked images of children looking for stone points and tools with their parents, and being inspired by Florida prehistory. James Dunbar doesn’t believe that it’s worth the risk to allow well-intentioned avocational archeologists to collect when he saw so many abuse the system. He believes that artifact collecting has been tainted by a market for antiquities that has seen out of state vendors sell Florida artifacts for thousands of dollars. Dr. Dunbar imagines a scenario. “Say you found, I don’t know, a Suwannee point, or maybe a Hillsborough point… and the thing ends up being worth six-to-eight thousand bucks. Would you turn that over to the state? Or would you say, ‘If I get sick, I can pay my medical bills.’?”

Beyond the morality of selling antiquities for financial gain, and the potential to go beyond the law for a lucrative pay day, Drs. Doran and Dunbar offer a scientific reason that a new Isolated Finds program wouldn’t work.

Is There Such a Thing as An Isolated Find?

“Let me drop a word on you,” Dunbar says. “Florida’s rivers are anastomosing.”

“I knew he was going to say that!” Doran laughs.

Entering a braid off of the Wacissa River on a canoe trip to Slave Canal. Anastomosing rivers move channels over time, and can split into multiple channels (like the many braids of the Wacissa). They are also slow flowing, as they typically occur in relatively flat places (as opposed to gaining momentum as they flow off of mountains).

Anastomosing rivers are low energy waterways occurring in low gradient floodplains such as are found in the relative flatness of Florida. South Carolina, which is the only other state with a program resembling Isolated Finds, has faster and more erosive rivers that drain from mountains. Florida rivers, it is said, can not carry artifacts far from context. “If you find artifact concentrations in a certain area,” Dunbar says,” you’ll probably find the in-place site in the banks.” In the previous video, Harley Means recounted how he and his brother found Simpson points in the Wacissa River during the Isolated Finds era. They reported it to Dunbar, and indeed there was what looks to be a fairly old site (which we visited with PhD candidate Morgan Smith during an excavation last June). Florida considers an artifact in context if it’s found within 90 meters of a site.

That’s the scientific argument against the program. There is also a philosophical argument, that people shouldn’t take anything from the water. “This is a non-renewable resource.” Says James Dunbar. If anything is to be taken, he argues, it should be done so carefully and with an eye towards adding to our knowledge of the past. It’s an argument that doesn’t fly to many of those who have left comments on our previous archeology posts. Reading them, you can clearly see that there’s a segment of the population that feels access to Florida’s artifacts should belong to all Floridians, and not just those in academia or the government. However, avocational archeologists do have ways to participate in the process without keeping artifacts.

Professional and Avocational Partnership Through Volunteering

Sitting between the two retired archeologists is Lonnie Mann, Membership Director for the Panhandle Archeological Society at Tallahassee (PAST). PAST volunteers team with professional archeologists on excavations, most recently at Wakulla Springs. There, they dug over 500 six-foot deep test holes, looking for concentrations of artifacts related to several occurrences. Touring the woods next to Wakulla Springs Lodge, Dr. Dunbar points to the remains of a Reconstruction era homestead. In another spot is rubbish from when the Wakulla Springs Lodge burned some decades ago. One main feature is evidence of the Kinnard brothers, one of whom had been a Seminole chief during the second Spanish occupation of Florida. The other is the paleo site I mentioned before, a site with the potential to rewrite the story of the first Americans.

This PVC pole marks one of 500 post holes dug by Panhandle Archeological Society at Tallahassee volunteers in Wakulla Springs State Park.

PAST Meets every second Tuesday of the month at the Governor Martin House, home of the Florida Department of State’s Bureau of Archaeological Research. “People make good friends.” Says Mann. “You have an opportunity for avocational people like me to hobnob with people like Glen and Jim and others, to learn about the field of archeology.”

The Governor Martin House is on the National Register of Historic Places as the home of Florida’s 24th governor, John W. Martin. It also sits on top of the most significant archeological site in Tallahassee, the winter encampment of Hernando de Soto in 1539 and 1540. During construction on a lot adjacent to the Martin House in 1987, former state archaeologist Calvin Jones noticed ceramics he felt to be consistent with that era. It was previously known that de Soto traversed the Florida panhandle and had camped in what was then Apalachee country, but no definitive sites had yet been produced. Jones mobilized volunteers as well as FSU Anthropology students and faculty to begin digging and “prove” the site.

Their work paid off. Having found chain mail, Spanish olive jars, crossbow belts, and other items associated with conquistadors of that time period, they were able to raise funds and negotiate with the developer to have the state buy the land and make it a state park (You can learn more about the de Soto excavation in the “Once Upon Anhaica” episode of WFSU’s history series, Florida Footprints). Says Mann, “The de Soto site there is considered really the authenticated de Soto site in North America.” PAST organizes digs around Tallahassee to look for further de Soto sites.

Aucilla Research Institute | Cutting Edge Technology Enhances Artifact Collection

Water is great at preserving a multitude of materials, but not everything lasts once it is taken out. “Suppose we go out here,” Dunbar says, pointing out into Wakulla Spring, “and find a wooden handle of some sort. And it’s got something hefted to it, a spear point or whatever… You’ve really got to do a lot of things to try to preserve it.”

If an ancient piece of wood is extracted from water, it has to undergo an extensive process to dry out and preserve it. “If you let it sit out for a very short period of time,” Mann says, “It turns to dust.”

Dunbar “One of the first things that should happen is it should be 3-D artifact scanned.”

Dr. Dunbar is a part of the Aucilla Research Institute, a Monticello based archeological research institution which recently received a grant for a 3D scanner. Once an artifact is scanned, they can create a replica without having to remove the original. This technology will allow researchers across the world to examine exact replicas of rare artifacts.

Another non-destructive technology is LiDAR – Light Detecting and Ranging. Using a pulsed laser, archeologists can scan through sediments to see buried material. Before digging their post hole grid at Wakulla Springs, the area was scanned using LiDAR to determine the best areas on which to focus. This saved excavators time and increased their efficiency.

New technologies allow archeologists to probe not easily accessible locations such as Wakulla Spring’s vent. Using Ground Penetrating Radar, a mastodon was detected under sediments here, and similar technologies would allow researchers to non-invasivley examine what could be a paleolithic kill site.

Ground Penetrating Radar is also useful in scanning through sediments in ecologically sensitive areas. Putting a GPR on one of the Wakulla Springs’ glass bottom tour boats, an irregularity was detected under the sediments of the spring run. It turned out to be a mastodon. A first mastodon was excavated from the spring in the 1930; you can see that one on display in the Museum of Florida History in downtown Tallahassee. At the time, it was not believed that humans had interacted with Pleistocene animals in North America, and so artifacts found around the mastodon were left unstudied. Dunbar hopes to investigate this second skeleton as a potential kill site.

“We haven’t even touched the mastodon yet” Dunbar says.

“And there’s no need to.” Adds Doran.

Technology is lessening the need for invasive excavation. And while 3-D scanning and printing may one day let anyone have an exact replica of a Simpson or Suwannee point, that may not be enough to satiate some collectors. In our previous piece on Isolated Finds, collectors mentioned the thrill of finding an artifact, and holding an something that had last touched human hands thousands of years earlier. Would it be enough to them to spot an artifact, leave it in the water, report it to the State Bureau of Archaeological Research, and perhaps receive a 3-D replica?

That’s a moot point if HB 803/ SB 1054 passes. In early January, the bill made it out of the House Economic Development and Tourism Subcommittee on an 11-1 vote. It is now waiting to be heard by the Transportation & Economic Development Appropriations Subcommittee.