Video: The dimpled trout lily isn’t a rare plant, but it is rare to see them as far south as Grady, County Georgia. There, volunteers from the Magnolia chapter of the Florida Native Plant Society set up a preserve for an unusually large concentration of the bright yellow winter flower. We visit the preserve and talk to members of the Magnolia chapter about the plants in our biodiverse region.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Ten years ago, Wilson Baker went exploring what was then a private timber operation in Grady County, Georgia when he came upon a vast yellow carpet of flowers. They were dimpled trout lilies, a flower common in the Appalachian Mountains, but not in the large concentrations he was seeing here at the extreme southern edge of their range. This out of place “floral display,” as Wilson calls it, inspired the Magnolia Chapter of the Florida Native Plant Society and the Georgia Botanical Society to raise money to buy the land for Grady County. Since Grady County didn’t have funds to staff it, volunteers maintain the Wolf Creek Trout Lily Preserve and lead tours during peak flower seasons.

Wilson Baker is considered one of our area’s foremost naturalists. Formerly a biologist with Tall Timbers Research Station, Wilson’s curiosity led him into the woods around Wolf Creek. There, he found acres of trout lilies in a bright yellow carpet.

Wilson wondered why this spot was blessed with such an unusual biological gift.

The theory he offers in the video is that the red clay under the flowers keeps the ground moister than another kind of soil might. That heaviness of the clay gives the Red Hills region a special relationship with water. As we outlined in our recent EcoShakespeare post on Wakulla Springs, that part of Georgia is the “streams” region of the Wakulla Springshed. The clay is so thick that most rain rolls off of it and into streams such as the eponymous Wolf Creek (which itself feeds the Ochlockonee River). Only one inch of rain per year fills the Floridan Aquifer in this region, but that water is slowly filtered by clay and is considered exceptionally clean.

I hadn’t given much thought to what water was doing to the surface above the clay. The trout lilies on the preserve lie on a long slope down to the creek, facing the east. It might just be a rare combination of a specific exposure to sun and a certain amount of wetness has given us, for just a few short weeks every year, a splash of color in an otherwise grayish winter.

Another splash of color comes from the spotted trillium (Trillium maculatum). It blooms at a similar time to the dimpled trout lily, typically in early to mid-February. Wilson pointed out that both plants had mottled leaves, which may or may not relate to their similar blooming habits.

When trout lilies are in bloom, the park is typically open more regularly, and with guided tours. Check their website in early February for up-to-date information.

Rare Plants of the Apalachicola National Forest

Harperocallis flava, also known as Harper’s beauty. Like many of the most striking flowers in the Apalachicola National Forest, this endangered plant is dependent on fire. Photo by Amy Miller Jenkins.

Like the trout lily, many of the unique flowers in the Apalachicola National Forest prefer moist areas. But where trout lilies are located in hardwood forests where the ground is relatively wet, flowers such as Harper’s beauty live between wetter hardwood and dryer pine flat wood habitats. That means Harperocallis and its carnivorous plant neighbors are on moist ground, but are also exposed to fire. Evidence of fire- or lack thereof- is what Florida Natural Areas Inventory‘s Amy Jenkins is looking for in historic aerial photographs on tonight’s episode of Dimensions (7:30 pm ET on WFSU-TV).

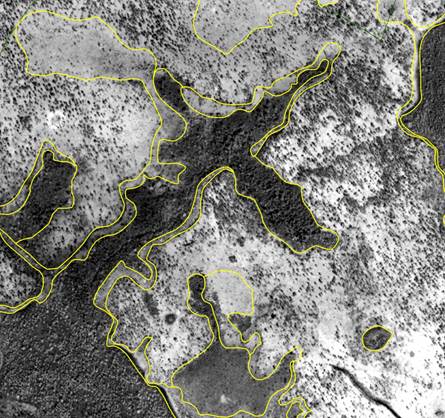

If you watched our SciGirls EcoAdventure at Tall Timbers last summer, you might be able to figure out what Amy is looking for when she compares historical and current aerial photos. In that video, we made a triple split screen showing plots of land burned at one, two, and three year intervals. Fire kills hardwoods and shrubs, so more frequently burned land (like the one-year plot) has more open space between fire resistant longleaf pine trees than infrequently burned land (like the three year burn plot). When Amy compares the two sets of photos, she’s looking for shrubs. If a modern pic has shrubs where they hadn’t been before, it may be that fire is being excluded where it shouldn’t. With this knowledge, the US Forest Service can resume burning those locations and possibly create more habitat for endangered flowers like Harper’s beauty.

… Decades later, they are filled with woody shrubs. This may be evidence that where fire once eliminated hardwoods, it has more recently been excluded. Aerial photos provided by Amy Miller Jenkins.

It’s heartening to meet people who are passionate about preserving rare and unique ecosystems. It’s hard to place a value on keeping these habitats intact – or as close to it as we can achieve. Nature lovers will of course travel to see a plant that’s endemic to a limited area, and there’s economic value to that. But we can value things for more than just their ability to fill wallets, and it’s comforting to know that people can work to keep from losing even just a small flower here or a hillside full of them there.

In a couple of weeks, we go from Wolf Creek, a Georgia tributary of the Ochlockonee River, to Bald Point State Park at the mouth of the river on the Florida Gulf coast. We meet up with author Susan Cerulean to talk about her blog and upcoming book, “Coming to Pass.”