The WFSU Ecology Blog was built on two pillars- communicating scientific knowledge about the natural world, and encouraging people to actively participate in it. When it comes to archeology in Florida, these ideals are at odds. Below is an attempt to stimulate discussion on the role of amateur- or avocational- archeologists in our state. It is a first attempt to capture the full complexity of the issue, which we’ll continue to explore as we cover archeology in the area.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU-TV

Much like citizen scientists often lead researchers to new finds, the video above originated not with the producer, but with the audience. It was part of a larger response to a pair of blog posts I wrote on underwater excavation in the Wacissa River. Many people were excited about the potential new information gained on the lives of early Floridians. Others were less happy about quotes I included from the researcher and a retired FWC officer about protecting the site from looters. Looking over the comments section of that first post, there was a sense that many of them felt that archeology in Florida had become the domain of a privileged few. These people feel that they should not be criminalized for pursuing their passion. I felt that this rift was worth exploring. I interviewed two parties for whom Florida’s paleo-history is a passion. Their argument: not all artifacts found in the water are of scientific value, and citizens have a right to collect those pieces.

So what artifacts advance the science of archeology? It’s a matter of context.

Protecting Florida’s Sovereign Waters

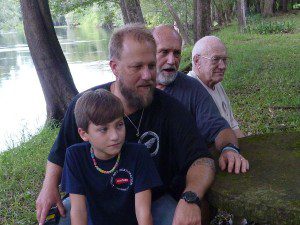

Four generations of the Pyles family (left to right): Corban, Teben, Thornton, and Kenneth. Thornton and Teben have taken their passion for paleolithic artifacts and turned it into a business; they make re-creations for museums and restore implements for out-of-state customers. The points used in Santa Fe river scene (Where Teben and Corban come upon a point on the river bank) were created by Teben and Thornton.

First, I traveled to the home of Thornton “Gomer” Pyles. During our interview, he was flanked by his father Kenneth to one side, and his son Teben and grandson Corban on the other, the Santa Fe River in the background. For them, amateur archeology is a family hobby.

When Thornton moved to Florida with his family in 1986, the Florida statute claiming all submerged lands as sovereign was almost 20 years old. Swamps and river beds, lake bottoms, and tidal lands- all of it belongs to the state, as do any archeological implements found there. But, Thornton recalls, law enforcement had no interest in artifact collectors. As Teben, president of the Tri-State Archeological Society, puts it, “There was already an informal partnership with the professional and the amateur.” The law looked the other way, and knowledge gained by collectors was shared with professional archeologists.

In 1995, Florida tried to formalize and regulate this relationship.

The Isolated Finds Program and the Wacissa Site

Like Thornton and Teben, Harley Means’ passion for archeology was a family affair. His father, Dr. Bruce Means, would take Harley along when diving on the Wacissa and Aucilla rivers. Dr. Means was working toward his graduate degree at Florida State University, and became interested in the fossils of extinct megafauna- the mammoths and other large animals found here when man settled Florida. The instant 5-year-old Harley saw his father emerge from the Aucilla with a spear point in his mask, he was hooked. That moment sparked an interest that led to a career in geology, and he always maintained an interest in archeology.

One day, Harley and his brother Ryan were scuba diving on the Wacissa when Ryan found what the brothers recognized as a Simpson point. Simpson was a paleolithic culture common in the southeast over 10,000 years ago. “It was amazing,” Harley remembers, “but, as you can imagine, being the older brother, I was a little jealous.” After changing his tanks, he returned to the spot of Ryan’s find. “And after about five minutes of diligent looking, sure enough, laying very close to the one that my brother picked up, was another spectacular example.”

The initial excavation of a paleo-site discovered by Ryan and Harley Means. In the water are Dr. James Dunbar (L) and Harley Means (R). Photo courtesy Harley Means.

At the time, Harley and Ryan were participating in Isolated Finds, a program established in 1995 by the Florida Division of Historic Resources (FDHR). Participants could collect artifacts found out of context in the water, as long as they reported their finds to the state. The state had 90 days to decide whether to keep the item. Harley and Ryan reported their find to Dr. James Dunbar, who worked for FDHC at the time. Two well-preserved specimens found in such close proximity indicated that there might be an intact site nearby. Sure enough, a bank on the Wacissa River was eroding and releasing implements into the water.

In 1999, Dr. Dunbar performed what he termed “salvage archeology;” taking the items most at risk for being lost and collecting them for the state. Harley and Ryan both participated. Since the riverbank was disturbed, the items lacked much of the data that researchers desire. It lacked context.

Morgan Smith’s Excavation

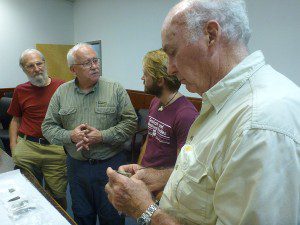

James Dunbar (center left) talks to Morgan Smith (center right). Morgan brought finds from his Wacissa excavation to the Florida Geological Survey, where Harley Means works as a geologist for the state.

In June of this year, the site was excavated by a team from Texas A & M University led by PhD candidate Morgan Smith. They methodically worked through the riverbank, taking fully buried artifacts and carefully logging data. These items were in context, and so there was more information to be gleaned from them. The arrangement of the artifacts hold clues as to the activities of the people who left them. The depth at which they were found within the strata of sediments gives researchers a clue as to their age. The same items would have had much less to tell Morgan and his team had they been found lying on the river bottom. If you’re interested in the methods and technology used to interpret the data collected by in context finds, I covered that in detail in my recent post about Morgan’s dig.

Morgan is waiting for radiocarbon dates for two of his items. The artifacts appear to belong to the Suwannee culture, which is currently believed have existed about 12,000 years ago. Harley points out, “Had the Isolated Finds policy and program not been in place, the site that my brother and I discovered would not have been reported, nor would over 10,000 artifacts that were reported to the state.”

The program ended in 2005.

Does Florida Need a Revised Isolated Finds Program?

After the end of Isolated Finds, Florida law enforcement has not been as casual about prosecuting violators. In 2014, Florida Fish and Wildlife officers arrested 14 in a sting called Operation Timucua. FWC claims those arrested were part of criminal conspiracy to buy and sell illegally obtained artifacts. Many in the amateur archeology community feel that those arrested were entrapped, that they were pressured into selling confiscated items by undercover officers. Most of those arrested had participated in Isolated Finds.

Archeological sites do get looted, and that threatens to deprive the public of knowledge regarding Florida’s heritage. The desire to protect these resources is at the heart of stings like Operation Timucua. But is Florida going too far in protecting implements of lesser scientific value? Teben agrees that parks and other protected areas should always be off limits, as well as sites containing in context artifacts. Harley would like a formal permitting system similar to what exists in South Carolina. They both feel that a more inclusive policy is conducive to citizen science, and would ultimately benefit the public’s knowledge.

There are detractors to the return of any form of Isolated Finds. In 2013, the Florida Public Archeology Network released a statement on a proposed Citizen’s Archeology Permit, a program that would be similar to Isolated Finds. FPAN was created by the University of West Florida to assist the Florida Department of Historical Resources, and was conceptualized by Dr. Judy Bense, who oversaw the commission that recommended the discontinuation of Isolated Finds. The statement points to a Florida Bureau of Archeological Research (FBAR) survey that “revealed approximately 78% non-compliance” from participants. This means that a large majority of the finds were not reported. The statement goes on to point out that South Carolina has faster moving rivers than Florida, so artifacts there would be carried further from context than in Florida. Florida considers an artifact in context if it is found within 90 meters of a site, so an artifact eroding from the bank is less likely to travel more than that in a Florida river. FPAN also sites the cost of the program, which Harley Means thinks could be covered with a permit fee. Philosophically, FPAN opposes a new program because “CAP is a program based on consumption.” In other words, allowing a potentially large group of people to remove artifacts could rob Florida of its heritage.

Kenneth and Teben Pyles look out over the Santa Fe River, sporting Tri-State Archeological Society t-shirts. Teben is working to one day be able to explore the river for loose artifacts.

Of course, Teben and Thornton Pyles would argue that Florida’s heritage belongs to its people directly, and not necessarily its government or academia. Is there a middle ground that serves the scientific interest while also including citizens in the process? Both the Pyles family and Harley Means evoked the image of a father and son finding a spear point on the Santa Fe River. To Harley, picking the piece up with the possibility of keeping it- that could spark a kid’s interest in science as it once did for him. On the other hand, is there a danger in inviting the general public to look for artifacts? FPAN is concerned that it couldn’t be managed in such a way to account for all artifacts taken, and to ensure that the artifacts taken were in fact isolated.

Harley Means believes that having more amateurs involved would benefit science. “By having a support group of avocationals, that is guided by the professionals to do things that mutually benefits both professionals and avocationals, is somewhere that I would really like to see the state of Florida go.” That seems like an ideal arrangement, but how does Florida get there?