Native plants are more than showy wildflowers and muhly grass. Now, don’t get me wrong- I love those plants. But I’ve been noticing, as more and more people write about the importance of native landscaping, that the landscapes portrayed have a certain look. I’m saying this as a person who has spent good money on coneflowers and sunshine mimosa and pink swamp milkweed. There are other natives that want to grow in your yard for free, if you let them. It’s time to embrace weeds.

I’m not telling your to just let everything grow. I’m talking about incorporating weeds into your game plan. It’s a cost effective way to increase plant diversity, and, in turn, insect diversity. This is key. A 2018 study connected declining bird populations to a decline in native plants. Most urban songbirds eat insects, and often, insects only eat the native plants they’ve evolved with. The study concluded that to maintain stable bird populations, our yards need to have at least 70% native plant biomass.

To make that >70% a fully functioning ecosystem, you’ll need to make sure you have larval food plants to feed caterpillars, plenty of nectar, and grasses and shrubs. Trees are critically important as well.

It’s fun to buy all of these cool looking natives and arrange them in a way that pleases our aesthetic sensibilities. I think this has been a big selling point in convincing people to plant native. Consider, though, the value of letting parts of your yard get messy. Consider giving space to boring or strange looking plants, and to those surprisingly beautiful little guys you don’t notice until you’re right on top of them.

There are a lot of plants you won’t find in nurseries, but that have value to the wildlife in your yard.

Knowing What’s Growing

Today, I’ll share my strategy for incorporating weeds into your landscape, and below I’ll list, with photos, some of my favorites from those that grow in my yard.

The first and most important step is to identify what’s growing. If you decided right now to step back and let your yard do what it wanted, a lot of what would grow would be nonnative. You might even get some aggressively invasive plants. Or you might get natives that don’t fit a space. You don’t want vines getting under your siding, or a shrub growing where there’s too little space for it.

So it’s good to know what you have.

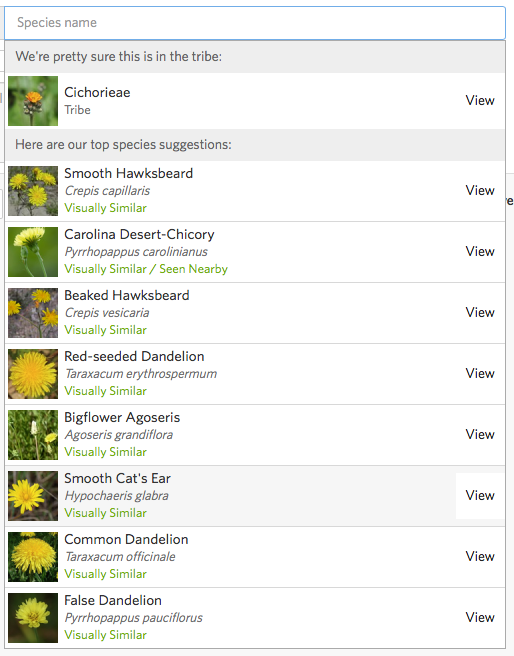

However, even in my relatively small yard, I’ve identified dozens of species of weeds. It can be daunting. Realistically, most of us don’t have the time to seriously research every plant we see. That’s why iNaturalist has been such a game changer for me. It’s a free app, and it can be quick and effective when used properly. I emphasize- when used properly.

And it’s only one tool. I used to rely on Google alone to figure out what I was seeing. Sometimes I still use Google image searches to double check an iNaturalist identification. And there are a couple of sites I trust for plant info. But those subsequent searches are made easier by iNaturalist narrowing down my options.

Facebook groups and other online communities can also be helpful. Many of the practices that make a better iNaturalist experience translate to this environment as well. It starts with your photos.

Making Effective Observations in iNaturalist

The way iNaturalist works is that you take one or more photos, upload them, and the app provides you with suggestions based on what it sees. You select the choice that best fits the plant in front of you, and then other users, including biologists who act as curators, either verify or make new suggestions.

But your photos are key. The better your photos show the plant, the better the visual information available to the app and to the other users. The same goes for Facebook groups and online communities.

To get a good ID, plan on taking at least three photos:

1. Flower closeup, if there are flowers are present. You can make IDs when a plant isn’t flowering as well, but it might not be as accurate. If the flower is especially large or small, I might take a photo with my hand in it, to show scale.

2. Leaves close up. Especially for flowers with many lookalikes, leaves can help differentiate.

3. The plant as a whole. A closeup of a flower doesn’t tell you if the plant is a vine, a small herb, or a shrub.

4. You may notice other distinguishing characteristics. Maybe there’s a seed pod, or the undersides of the leaves look much different than the top, or the stems are red. If you’re IDing a tree, you want a photo of the bark.

Making an Effective Identification From Your Observation

You can upload photos straight from your phone, or you can also use a camera and upload the photos to the iNaturalist web site on a computer. I’ve been using my dslr because I can get better photos, especially of animals I don’t want to spook by approaching too closely; but it’s a couple of more steps than uploading straight from a phone.

So now you click on the species name field, and you get a list of suggestions. You can always change your identification, so don’t be nervous about getting it wrong the first time. There’s a link next to each species suggestion, where you can see more photos and read about the species.

You can also look at a range map when you click on the species name. This helps eliminate lookalikes or related species from other parts of the world.

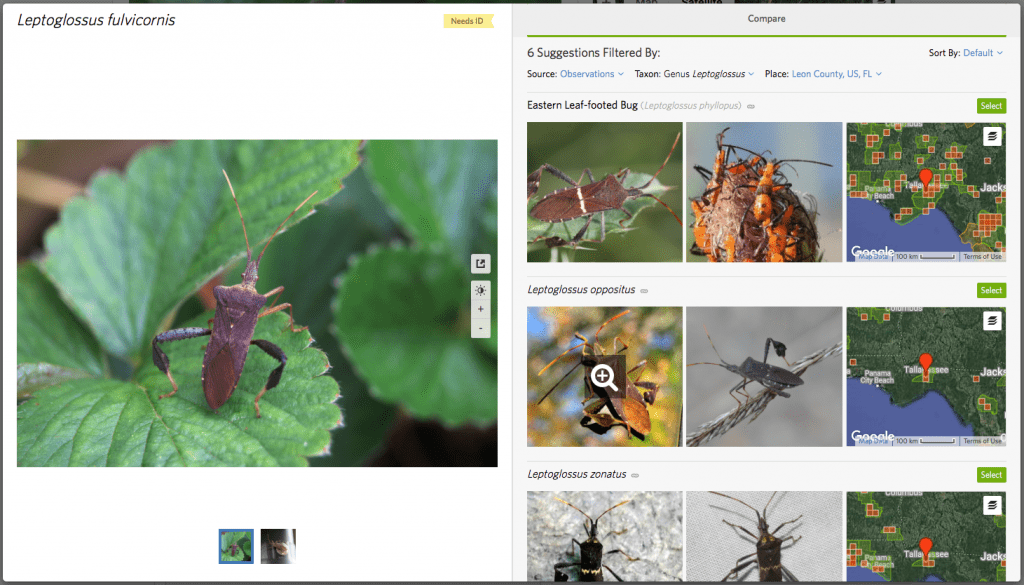

And you can always go back later and click compare, which places your photos alongside other members of the genus or family of your selection. This list is filtered by location, showing you the species that have been identified in your county. You can broaden the filter to show IDs in the state, and you might see something that has been identified in counties all around your own, making it not unlikely to be present in your county, even if it hasn’t yet been identified there yet.

Taking a second look and comparing might make iNaturalist feel a little less convenient to use. But it also makes it a more accurate tool. And we want to know what plants we have growing in our yards. We want to know that a plant has value before we let it stay in our yard.

Is it a weed after all?

There’s a saying about weeds; weeds are only plants where you don’t want them. Once we’ve made our ID, and, hopefully, it’s confirmed, how do we know if we want them?

I start with determining whether a plant is native or not. You can click on a species name in iNaturalist to learn more about it. But this is where you want to be careful; iNaturalist lists naturalized plants as native, as does the USDA web site. Some plants have been here long enough to have become established in our ecosystems after humans brought them from Europe or Asia.

So, in the plant’s page on iNaturalist, I scroll down and click About. Many times, even when it says a plant is native, its description will say it’s native to South America, or south Asia. I’ve even seen where it says a plant is native to several continents. So what do we do about these plants?

Let’s look at one case study where I decided to keep a nonnative plant.

Pennsylvania Everlasting (Gamochaeta pensylvanica)

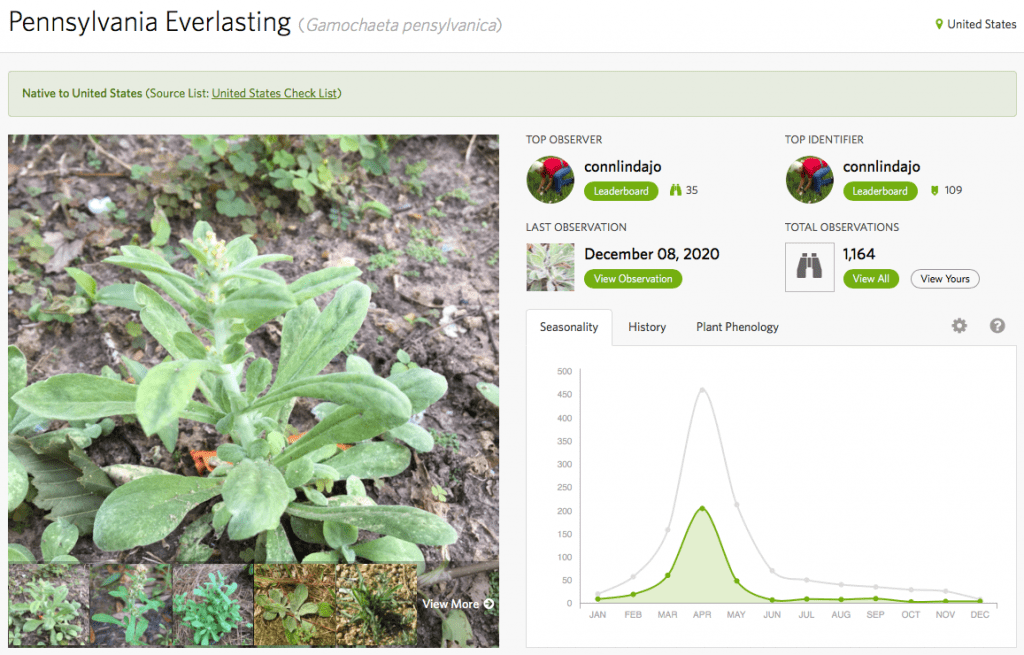

Here’s a plant that appears in the winter, flowers in the spring, and then disappears in the summer. This winter, it returned in early December. Anyhow, this is a plant I’ve identified three times in my yard. I sometimes end up identifying the same plant multiple times on iNaturalist, especially when I encounter a plant at different stages of its development. It’s part of learning about them.

The name suggests an American original, and when I clicked on the species name, I see a pleasant green box that says it’s Native to United States. Introduced species have a red exclamation point. Next, I scrolled down and clicked About – “It is native to South America and introduced into Eurasia, Africa, Australia, and North America. The pensylvanica epithet is a misnomer, as the plant is not native to Pennsylvania and only marginally naturalized there.”

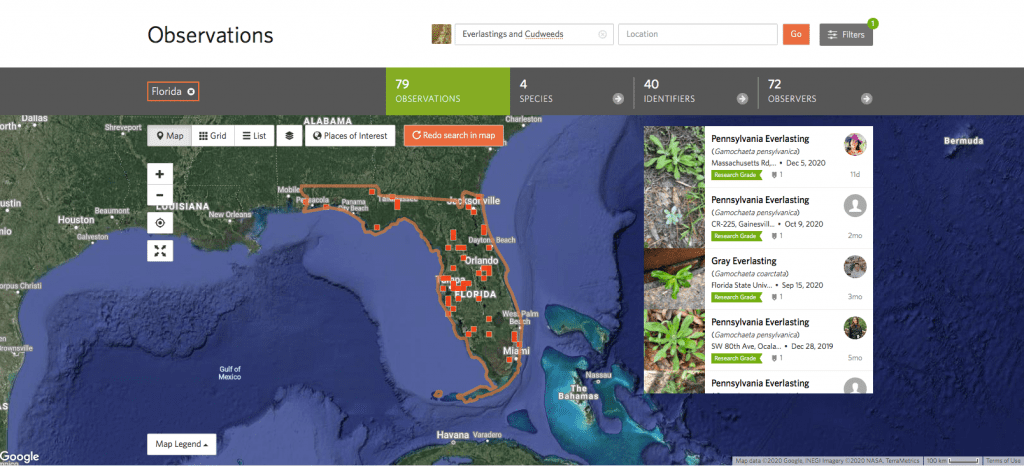

However, I also see that the plant is classified under “Everlastings and Cudweeds.” Cudweeds are the larval host food of the American lady butterfly. I looked up “Everlastings and Cudweeds” under the explore tab in iNaturalist, setting the filters to “Research Grade” and setting the location to “Florida.” This lets me see all verified cudweeds in the state, from all users’ observations.

The vast majority of the verified cudweeds in Florida are Pennsylvania Everlasting. And I don’t have other cudweeds in my yard. I don’t know how plentiful native cudweeds once were in Florida, or whether this nonnative has displaced them. So I decided to let them grow and see if I could attract American ladies.

I never saw the caterpillars, but I did see the butterflies. Maybe they hosted in the yard, or perhaps nearby. For every butterfly I see, likely several of its caterpillar siblings fed birds. I only saw these butterflies in May, which lines up with the availability of their host food.

Wild Zones: Your Native Plant Learning Laboratories

To identify the plants, and go through the process of deciding whether or not to keep them, I first have to let them grow. I have a feeling this is the part of the process that many people are going to have a problem with. It takes a sense of adventure and curiosity, and a willingness to watch and observe.

Maybe you have a small sections of your yard to let grow wild. Think of this as your lab. Here, you’ll learn about the good and the bad. And then in other parts of the yard, you might let a cudweed or a native geranium or a groundcherry pop up and make a home for itself. Once we know what a plant or animal is, we know what value it can offer our home ecosystem. But we have to allow ourselves to get to know it.

The value, as I’ve seen it unfold in my yard, is in the wildlife I see. The American ladies that host on Pennsylvania everlasting, or the checkered skipper butterflies that host on fanpetals- those are of course cool. But to me, it’s about the overall variety of insects I see. Some are fascinating, others mundane. But there are so many different kinds.

This variety feeds some of my favorite backyard critters- insectivores.

For instance, this year multiple species of birds brought their fledgelings into the same overgrown patch of yard to forage for insects.

We also welcomed a couple of bug-eating baby skinks into our backyard food web.

And then there are predatory insects. They help keep plant eating insects in check, even if they break our hearts sometimes and go after the ones we like.

A diversity of predators feeding on a diversity of plant consumers- this is a healthy food web. And it’s supported by a diversity of plants that I could not have achieved without the many weeds growing in my home ecosystem.

Additional Reading: Sites I Trust

You may decide to seek further information on a certain plant. If so, I find it helpful to search using its scientific name (such as Bidens alba) instead of its common name (like Spanish needles, which is also a common name of Bidens pinnata). Some plants have multiple common names, or sometimes several plants end up with the same common name.

In my example above, I found a nonnative plant with beneficial qualities. But many exotic species, away from their natural predators and competitors, can grow unchecked and take over large areas of your yard. You can check the USDA Noxious Plant list for Florida to see if you have one of these. There aren’t photos, so this is a site to check after having first identified your weed.

For information on a plant’s native status, range, and seasonal information, I like the Florida Native Plant Atlas (maintained by the University of South Florida) and wildflower.org (maintained by the University of Texas). One of the databases used by the Florida Native Plant Atlas is iNaturalist.

When I’m Googling plants, I sometimes find articles and blog posts from University of Florida/ IFAS extensions around the state. These have a lot of useful information.

The Leon County IFAS extension worked with us to create a guide to woody vines in north Florida. Homeowners don’t always love vines, but there are many native species with wildlife benefits. There are also some nasty invasives.

And lastly, I document my own plant and insect discoveries on the Backyard section of this blog. It’s not a reference page like these other sites, but I’ve been paying close attention to everything that lives in my yard, and I’m always blown away by how much biodiversity can exist in such a relatively small space.

A few weeds with wildlife value

The following are just a few of the native plants that just show up in my yard. They’re not flashy, and I wouldn’t spend money on them at a nursery, but I’ve grown to love them.

These weeds grow in a small, largely paved yard near downtown Tallahassee. Many north Florida homes have larger yards next to forests and waterways, and in much more rural settings. Those yards have many more plant possibilities than mine. The following plants can still be found in such environments as well, but these are all plants you could expect in places where humans have altered the landscape. Such places are vectors for exotic invasive species as well, which is why it’s important to know the plants in your yard.

Fanpetals (Sida genus)

Anyone who has paid attention to the Backyard Blog has read my endless praises for this plant. It ticks off multiple boxes on the wildlife value list. It’s a butterfly larval food, a nectar source for pollinators, and birds eat insects off of it.

iNaturalist lists six fanpetals for Leon County, and I think this one is Cuban jute (Sida rhombifolia). It grows into a short woody shrub, even when it grows out of a crack in the pavement. So this is one of those beneficial plants that you want to make sure is growing in the right spot for your yard. I have a couple of patches where I let this become established, the main one is mixed with scarlet sage.

Fanpetals are the larval host food for checkered-skipper butterflies. I have plenty of these butterflies in my yard, have seen them appear to lay eggs on the plant, and have even seen eaten up leaves. And yet, I’ve never seen the caterpillars.

Its flowers are popular with smaller native bees, butterflies, and hoverflies. To give you an idea of the size of the insects, fanpetal flowers are about 1.5 centimeters wide.

I often see birds foraging in the fanpetal patch. In addition to checkered-skipper caterpillars, there are plenty of other insects to eat.

Groundcherries (Physalis genus)

There are a handful of Florida native Physalis species; I think this one is cutleaf groundcherry (Physalis angulata). The genus includes the tomatillo, and angulata makes edible fruit as well. I’ve never seen an animal eat the fruit, but something is spreading the seeds around year after year. I’ve also iNaturalized another Physalis species on the Garden of Eden Trail.

This is what the plant looks like:

As the fruit matures, its husk gets papery, like a tomatillo.

When the fruit is ripe, it drops to the ground. Its papery husk is brittle and makes the fruit easy to access for whatever animal wants to eat it.

Slender Three-seeded Mercury (Acalypha gracilens)

Here’s a plant I noticed for the first time this year. It’s not flashy at all, but I’ve noticed holes in the leaves and once saw a cardinal pecking at it.

I’m including in this post it because it does add to our food web. But also, it turns a spectacular color in the fall:

Carolina Crane’s-bill (Geranium carolinianum)

Here’s one of the many early season plants that bloom in the yard.

This is a source of nectar at a time when the rest of my garden flowers have yet to bloom. As it goes to seed, you can see where the crane’s-bill name comes from.

The seeds feed backyard critters. Native wildflower seeds are an important food source for all sorts of animals, so you may consider leaving seedheads alone, even if many of us don’t find them attractive.

Ohio Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis)

This is a common weed that becomes widespread in a grass yard. The flower itself, close up, is attractive. And it’s edible. A field of these is not always so nice looking, especially once it starts going to seed.

This is a native plant, and it blooms early in the year, peaking in the summer. In early 2020, my little field of spiderworts bloomed before my purchased flowers. This made the flowers popular with the early flying bee species- honeybees, bumblebees, and carpenter bees.

Are they as attractive as coreopsis, sage, loosestryfe, or coneflowers? Maybe not. But they supported pollinators for a good month before those other flowers started blooming in my yard.

Other spring blooming flowers

In the spring, there are several small flowers I notice in the grass. Some of them are pretty, but easy to miss. These are all native, and let you experience a little bit of seasonality in your yard.

These started blooming in the last weeks of a warm winter last year, disappearing by summer. Other than the fanpetals, I don’t have many native weeds that flower in the summer. Many of my purchased/ seed planted flowers start blooming in the spring, and persist through the fall. I also have some late summer and fall blooming flowers. If you visit the forest at different times of the year, you’ll see different flowers in bloom. You want to mimic this in your yard. If you can provide a succession of nectar sources throughout the year, you’re more likely to see pollinators.

Rice button aster (Symphyotrichum dumosum)

In north Florida, asters and aster family plants such as goldenrod are important nectar sources in the fall months. I haven’t been lucky enough to have goldenrod volunteer in my yard, but it’s widespread in the late fall.

In my small yard, I’ve been lucky to have these small asters pop up. There are a large variety of asters native to our area, many of which grow as weeds but also many that can be bought at nurseries.

The weeds in our yards can help us maintain that succession of native nectar sources throughout the year. But, especially in a small yard like mine, you’ll likely have to bring in additional plants. For instance, the smaller bees had disappeared from my yard by September. And then, in early November, I saw swarms of sweat bees and other pollinators on aster bushes at Fred George Greenway. I think I’ll buy some asters for next fall, to compliment the few that have volunteered in the yard.

Carolina Ponysfoot (Dichondra carolinensis)

EDIT September 2021- This article had originally included Florida Pusley and Straggler Daisy as native ground cover plants, but neither is native to North America.

I’ve bought native ground cover plants such as fog fruit and sunshine mimosa. But I also let a couple of native volunteers spread out and cover some ground. You’ll notice that, unlike turf grass, you can still see a fair amount of earth beneath this and other native ground cover plants. It’s not a total coverage. This allows space for ground nesting insects, including many native bee species.

Spanish needles (Bidens alba)

I almost didn’t include this plant. It’s everywhere, and it’s not terribly exciting. But it makes flowers throughout the year, flowers that many pollinators like. Florida Native Plant Society’s Lilly Anderson-Messec called it one of the three most important plants for honeybees in the southeast. Honeybees are not native (though they are an important agricultural animal), and if it’s warm enough, they may be flying in January. There just aren’t really many flowers in bloom then.

Bidens alba provides good value, but it really does cover ground. Like I said earlier, you don’t have to just let everything grow. It’s up to you how you incorporate this and the other plants that volunteer in your yard. Just know that there are dozens of species you can let grow with the plants you’re cultivating, to create a diverse and wildlife friendly home ecosystem.

Dig Deeper into Backyard Ecology

What can we do to invite butterflies, birds, and other wildlife into our yards? And what about the flora and fauna that makes its way into our yards; the weeds, insects, and other critters that create the home ecosystem? WFSU Ecology Blog takes a closer look.