We take an eye level look at the habitat of the Hillis’s dwarf salamander, a species new to science. Our guide is Dr. Bruce Means, who, along with other researchers, discovered the salamander along regional waterways. A few months ago, we spent a day in the forest with Dr. Means and an eastern diamondback rattlesnake.

This is part one of a three part took at Dr. Means’s work with salamanders. Part two takes us into the Bradwell bay Wilderness in search of Southern Dusky salamanders. Part three takes us down into a steephead ravine by the Apalachicola River in search of the Apalachicola dusky.

Rob Diaz de Villegas WFSU Public Media

After about an hour of searching for salamanders, Bruce Means stops to grab a drink. It’s a hot summer day, and about time for some cool refreshment. He gets down on his hands and knees and presses his lips against the muck on the slope. There, cool, clean water is seeping from an underground lake, creating the ecosystem favored by the subject of our search.

This is the Hillis’s Dwarf salamander (Eurycea hillisi), a species new to science. It’s here somewhere under the sphagnum moss carpeting a seepage slope by the Chipola River. Dr. Means is showing us some of the work that went into the discovery of the species. His hands are in the muck, plucking bits of sphagnum off the slope as his eyes scan for tiny fleeing critters. As he works, spiders and insects are crawling all over him. (Check that spider spinning a web off him at 01:29).

Watching this field work, I’m reminded of a visit to my first grade son’s classroom at the beginning of the school year. Max’s science teacher explained that they were starting their science curriculum by learning about the five senses as a toolkit for collecting data. Right now I’m seeing this toolkit in action. Dirt under his fingernails, Bruce Means’s hands and eyes are working furiously. He’s tasting the water that makes this a habitable environment for the salamander. He’s fully engaging his senses in the world of this animal.

And that’s a big part of why I’m doing a three part salamander adventure with him. It’s not just about slimy little creatures that live in wet, buggy places. It’s also about the places themselves, and the salamander’s relationship to the other plants and animals there, and the underlying geology.

We’re focusing on three species of salamander, though we’ll find a few more. And, in our muck-level exploration of three different wetland ecosystems, we’ll get up close and personal with a few other plants and animals species as well. Next week, we go deep into a titi swamp, and climb down into a steephead ravine. Right now, we’re on the hunt for dwarf salamanders in the floodplain of the Chipola River.

The Eurycea quadridigitata Complex | Five From One

The Hillis’s dwarf salamander was “discovered” by Bruce Means, of the Coastal Plains Institute and Florida State University, and fellow FSU researchers Kenneth Wray and Scott Steppan. While the word discover implies that no one had ever seen this animal before, it’s not entirely new. Science just hadn’t fully figured out what it was.

The species name Eurycea quadridigitata means four (quad) toed (digit) dwarf salamander (the Eurycea genus). Dwarf salamanders are small and live in habitats that often leave them covered in muck. When it comes to small, similar looking animals such as these, distinct physical differences help tell one species from another. Since other dwarf salamander species have five toes, salamanders with four toes were all lumped into one species.

Over time, however, Bruce Means would notice further differences between the four-toed dwarf salamanders. Taken out of the muck and cleaned up, their markings are more obviously different. And they’re found in a wide range of wetland habitats.

But some species of salamander can vary in their appearance, so we need more than our eyes to say that they’re different animals. This is where Bruce Means’s mucky field work meets Kenneth Wray’s higher tech DNA analysis. What they found was that Eurycea quadridigitata was at least five different species. Two of the species are new to science, while two other existing species living further west are now recognized as having a common ancestor with the other three.

These animals have their similarities, but, knowing their differences, we can better understand how each species fits into its environment.

Bruce Means walks out of the swamp (right) and heads up slope. The slope occupies a space between the swamp and drier upland forest, a transitional zone known as an ecotone. Ecotones, at the edges of two or more ecosystems, tend to have rare plants and animals.

The Seepage Slope- Home to the Hillis’s Dwarf Salamander

Bruce Means is knee deep in a brown, viscous sludge. “One of the places I dearly love is a swamp like this where you find muck.” He says.

We’re standing at the bottom of a bowl. Cool water seeps from a hill side, collecting down here in a mucky cypress swamp. Above the rim of the bowl, a dryer hardwood forest in the Chipola River floodplain. We can see three different habitat types within a short distance.

Two salamanders in the E. Quadridigitata complex are here. The two species can be just a few feet apart, and yet their habitat is different enough for each to occupy its own niche. The Hillis’s in particular has adapted to this slope environment. It’s a little known ecosystem type that supports a lot of plants and animals found nowhere else.

An Underground Lake Seeps Out

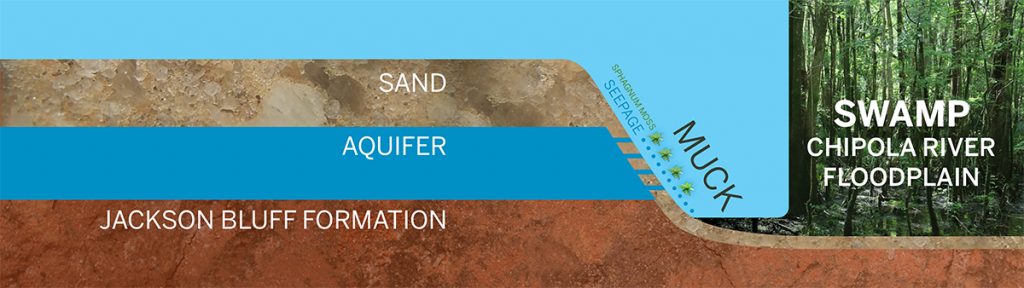

“This hill is made of sand,” Dr. Means says. “And a huge underground lake underlies the sand. It’s perched on something called the Jackson Bluff formation.”

The Jackson Bluff formation is a geological layer of sand, clay, and mollusk fossils formed between five and three million years ago. It’s a hard layer under soft sand. Water passes easily through the soft sand, then runs into this harder layer, forming an underground lake.

As the slope of the hill erodes and moves over time, it exposes this lake, which seeps out in little trickles from the side of the hill.

The lake is a surficial aquifer. Our source of drinking water is the Floridan Aquifer, a much larger network of stored underground water. The Floridan holds water deep beneath the ground, and connects to the surface in springs and sinks. Surficial aquifers, as the name suggests, sit closer to the surface. But, it’s still protected ground water, and it’s a similar temperature to spring water.

“The animals and the plants that live in this kind of seepage environment are extremely adapted to the buffered thermal regime of the water that sleeps out of the slope.” Dr. Means says. “And that’s why the sphagnum bogs and all the little salamanders are uniquely adapted to this kind of habitat, and are only found in it.”

These slopes are perpetually wet, and so make a good place for sphagnum moss to grow. Sphagnum, or peat moss, carpets boggy environments. As the lower layer of the carpet decomposes, it turns into peat soil, which is favorable for carnivorous plants and orchids to grow in.

To review, this is a constantly wet environment. Its water temperature is a consistent 68 degrees, which feels cool in the summer and allows cold blooded amphibians to survive in it during the winter. The sphagnum provides cover from predators. It’s a great place for salamanders to live.

And in fact we find several species here. One is an Apalachicola dusky salamander, an animal we’ll meet formally next week. It lives in steephead ravines, which have similar seepage. We also find one of the five-toed cousins of the Hillis’s, the three lined dwarf salamander (Eurycea guttolineata).

And of course, we find two of the salamanders we came to see:

The Silver Bellied Dwarf Salamander | Eurycea quadridigitata

The first salamander he finds is the one that kept its original Eurycea quadridigitata name, the silver bellied dwarf salamander.

As the little guy tries to escape his hand, Dr. Means says “So the other one is probably further upslope, ‘cause that’s where I found them before.”

In their paper on the new species classifications, Means and his collaborators describe each salamander’s habitat. While E. quadridigitata has been found in a few different types of habitat, they ” have observed that this species utilizes breeding wetlands associated with cypress.” (page 36 of the PDF). And so, it makes sense that it would be found lower on the slope, closer to the swamp.

The Hillis’s Dwarf Salamander | Eurycea hillisi

The Hillis’s dwarf salamander is often found close to the silver bellied. “This species inhabits steephead/ravine systems where it can be found in close proximity to typical E. quadridigitata breeding habitat in the floodplains of major creeks and rivers.” (page 41)

While we’re not in steephead ravine today, this slope seeps like a steephead. Next week, we’ll visit a steephead with Dr. Means in search of the Apalachicola dusky.

So far, Dr. Means has only found the Hillis’s between the Chipola and Choctawhatchee Rivers in Florida, and north of that along the Chattahoochee river corridor in Georgia and Alabama. But it is a new species, and they may turn up in different locations.

The Bog Dwarf Salamander | Eurycea sphagnicola

Eurycea sphagnicola, the bog dwarf salamander on a bed of sphagnum moss. Photo courtesy Bruce Means.

West of the Choctawhatchee River, we find two other members of the E. quadridigitata complex. As Dr. Means explained to me, all of these dwarf salamanders once had a common ancestor that covered, more or less, the combined range of its successors. Different populations became separated by rivers and, isolated from each other, evolved into new species.

West of the Choctawhatchee River, the bog dwarf salamander replaces the Hillis’s on seepage slopes. As its scientific name implies, it too is at home in sphagnum moss.

Seepage slopes in the western panhandle look a bit different than the dense, swampy place where we are today. Those slopes occur in a more open pine flatwood environment; there, seepage is feeding pitcher plants and other carnivorous plant species.

The Western Dwarf Salamander | Eurycea paludicola

As we move further west, we find the western dwarf salamander. This swamp dweller is found mostly in Louisiana and southeast Texas, with some specimens also found in Alabama.

Genetic work shows two “deep lineages,” within the species, evidence that even this species could be further divided. There’s still a lot we don’t know about these dwarf salamanders, and more research may reveal new insights about them.

The Chamberlain’s Dwarf Salamander | Eurycea chamberlaini

Up north, we find the other dwarf salamander species new to science. The Chamberlain’s dwarf salamander is found in North and South Carolina.

Its habitat is a little bit different than the other salamanders in this complex. Instead of swamps and seepage slopes, this little guy has been found in stream edges and at spring outlets- in moving water. In this way, it’s more like five-toed salamanders than it is to the other four-toed species.

What Don’t We Know About the Hillis’s Dwarf Salamander?

Bruce Means has collected 30 or 40 Hillis’s dwarf salamanders from about ten locations. They’ve done the DNA work, so they know it’s a species. And they know its range and habitat. But there is still a lot to learn.

It’s something that Dr. Means reflects upon when we haven’t found any after an hour of searching.

“Although at one time, when I was looking for them (here), they were quite abundant.” We’re searching on a hot July day, and he had found his specimens during a cooler time of year. “Do they migrate? Was I finding them only when they were migrating to wet places like this to lay eggs?”

Last year, I visited Dr. Means’s son Ryan as he and his wife Rebecca released striped newts into the Munson Sandhills. Striped newts breed in ephemeral wetlands, which dry out from time to time. When the wetland is dry, striped newts and other salamanders and frogs then move up into the drier pine forest.

Could the Hillis’s dwarf salamander make a similar migration?

“This is a great masters thesis for somebody,” Dr. Means says. “You could put a drift fence up here,” at the top of the slope. In the striped newt project, these short metal fences surround each wetland. When striped newts leave, or return, they bump up against the fence, following it until they fall into a small cup. Researchers and their volunteer helpers check the cups daily, and see how often newts move in and out of the wetland.

It’s a lot of work for a little slimy creature we rarely ever see. And this brings us back to the question Bruce Means asks at the start of the video.

Rebecca Means checks a drift fence around a striped newt repatriation pond. The young volunteers surrounding her helped the Coastal Plains Institute release the endangered newts into wetlands in the Apalachicola National Forest.

The Case for More Salamander Research

“You might well ask, ‘Well, what’s the value of a salamander? Or any kind of creature, or plant?'”

Bruce Means is a herpetologist. He studies animals that give some people the heebie-jeebies- snakes, lizards, and salamanders. In his fifty-plus years of doing this, he’s had a lot of time to think about why it matters.

“It turns out that there are by far more salamanders, frogs and snakes than there are mammals and birds.” He says. “And yet we know way, way less about them.”

Like the Hillis’s dwarf salamander. If the Hillis’s leaves the seepage slope, where does it go? What does it eat? What eats it?

This small animal has a relationship to the plants and other animals around it. It found a home in a waterway created by a specific geology. The more we know about this salamander, the more we know about all of these other living things, and about the environment they inhabit.

For all the great information that’s out there about our ecosystems, there’s still a lot we don’t know. The fun thing is that people are working to find out. And for those of us with a connection to the outdoors, it’s a chance to see our local ecosystems in a new light.

Next week we visit two iconic north Florida wetlands- the swamps of the Bradwell Bay Wilderness, and a steephead ravine in the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines region. It was in these places that, fifty years ago, Bruce Means made his first salamander discovery.

A fallen log in the forest serves a number of ecological roles. As its wood is broken down by fungi, it softens and becomes a habitat for animals such as insects, snakes, and even salamanders.